“Why do they call, sonny, why do they call for men who are brave and strong?

Is it naught to you if your country falls and Right is smashed by Wrong?

Is it football still and the picture show, the pub and the betting odds?

When your brothers stand to the tyrant’s blow, and England’s call is God’s?”

A poem from the Paignton Observer 1914

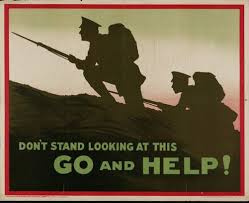

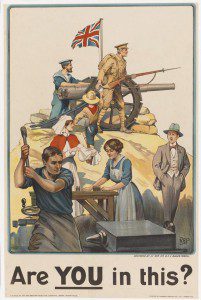

The Great War began in August 1914. It was immediately realised that many more soldiers were needed to turn a small professional force into a vast citizen army able to defeat the world’s most formidable military machine.

A wave of enthusiasm and volunteering greeted the outbreak of war. Yet, the real surge in recruits began in the last week of August, when news of the British retreat following the Battle of Mons reached home. By the end of September, over 750,000 men had enlisted. Indeed, it wasn’t unusual for all the young men of a family to sign up – the seven grandsons of Mrs Wills of Paignton’s Colley End joined the forces, for instance.

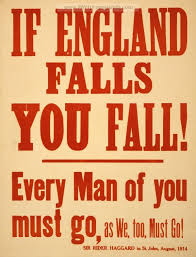

Newspaper advertisements calling for volunteers were not only directed at eligible men, but also at their employers who were sometimes reluctant to lose their entire workforce overnight. To persuade potential recruits to quickly join up the impression was given that the war would be over in a few weeks. The Bay’s newspapers warned young men not to miss out, “The war may end by Christmas.”

By early November, however, the Paignton Observer had begun to recognise that, “The war may not end soon. Not a few are talking about a 3, 5 or even a 7 year war!”

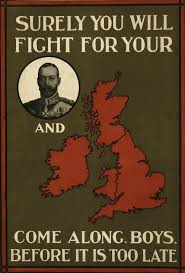

In September the first recruiting meetings were held in London. These were quickly replicated in the Bay with weekly recruiting concerts and marches inviting volunteers, “to crush the German savages who masquerade as a civilized nation”.

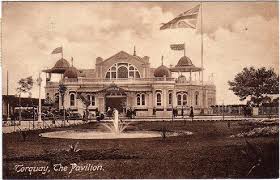

Pressures to enlist were intense. One evening in September of 1914 a gentleman by the name of David Cunningham-Anderson was driving his automobile past the Pavilion. He noted that, “All its doors were opened wide and from them were issuing dense masses of women. They crowded the pavements; the streets were black with them wending their way home. They seemed of all ages; representatives of all classes of society. When I got out of the car at the Strand, I ventured to ask two old ladies what it had all been about. ‘It was’, they said ‘a meeting of women, in connection with the War… in order that they may stimulate these men to come forward’. And then one of them – perhaps in the dusk she misjudged my age – looked at me pointedly, and in a tone of voice, the meaning of which there was no mistake, remarked ‘It’s evidently wanted!’”

Pressures to enlist were intense. One evening in September of 1914 a gentleman by the name of David Cunningham-Anderson was driving his automobile past the Pavilion. He noted that, “All its doors were opened wide and from them were issuing dense masses of women. They crowded the pavements; the streets were black with them wending their way home. They seemed of all ages; representatives of all classes of society. When I got out of the car at the Strand, I ventured to ask two old ladies what it had all been about. ‘It was’, they said ‘a meeting of women, in connection with the War… in order that they may stimulate these men to come forward’. And then one of them – perhaps in the dusk she misjudged my age – looked at me pointedly, and in a tone of voice, the meaning of which there was no mistake, remarked ‘It’s evidently wanted!’”

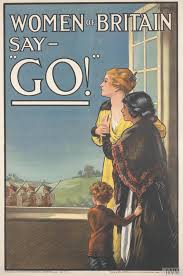

Local newspapers had been raising concerns that not enough men were coming forward. They commanded, “Wake up, Devon. Recruiting very poor so far.” David, still presumably smarting from being taken as faint-hearted, asked: “What ails the young men of Devon? Has it really come to this, that men, Englishmen, have to be prodded, stimulated and pushed into action by women? What is the matter? Have young English men lost the spirit of adventure, that spice of danger which fires the blood? Does the Romance of War no more affect the imagination of the ardent and generous youth?”

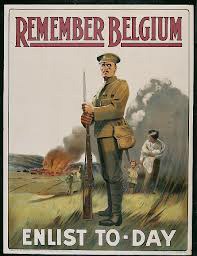

To promote recruitment the government began a poster campaign and the War Propaganda Bureau published pamphlets to promote stories of German abuse and torture of Belgian civilians. Perhaps David had this in mind when he wrote, “Surely this is not the time for men to be idling – not even playing games but simply loafing around the front, flirting with ‘flappers’. I have seen dozens of girls – many of them not too modestly dressed – go glancing, flirting, laughing by. I have wondered: What would be the fate of these girls if the Germans obtained military occupation of this district even for forty eight hours?”

Reminders of the cost of the war were everywhere in our three towns. Belgian refugees arrived along wounded soldiers – by November there were 180 patients at Oldway Hospital. German bullets extracted from the bodies of wounded soldiers could even be seen exhibited in the window of a Paignton jeweller.

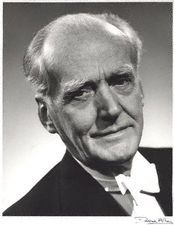

Predictably, anti-German sentiment was rife. Letters to the local press warned of spies disguised as “German waiters”, while the Pavilion’s musical director Basil C Hindenburg (pictured left) found it wise to change his name to Basil Cameron – something a little less foreign-sounding.

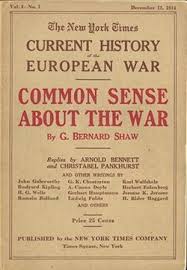

Suspect foreigners were detained.  While holidaying in Torquay the author George Bernard Shaw (pictured right) recounted the arrest of the German novelist Hedwig Sonntag who was working as a hotel porter at the Hydropathic Hotel above Meadfoot Beach, “Though registered, he was handcuffed and deported to the innermost centre of Britain – to Exeter, in fact. And in the evening the Coastguard threatened to shoot me and Barker on our walk before going to bed, if we approached him (we were 50 yards off).”

While holidaying in Torquay the author George Bernard Shaw (pictured right) recounted the arrest of the German novelist Hedwig Sonntag who was working as a hotel porter at the Hydropathic Hotel above Meadfoot Beach, “Though registered, he was handcuffed and deported to the innermost centre of Britain – to Exeter, in fact. And in the evening the Coastguard threatened to shoot me and Barker on our walk before going to bed, if we approached him (we were 50 yards off).”

One of the few to raise an alternative view about the conflict was Shaw. It was in Torquay in 1914 that he expressed his opinions in a series of newspaper articles under the title ‘Common Sense About the War‘. The essays appeared as a Special War Supplement to the New Statesman in November 1914 and they were later reproduced in newspapers such as the New York Times. He gave a copy to a friend. It was inscribed, “written on the roof of the Hydro at Torquay”. In the articles he recognised that winning was a practical necessity, but he refused to glorify the conflict in any way. He held that war could have been avoided, but was the product of a bankrupt political system, a system that required total change. Few public figures had dared to speak out in opposition to the War and the response to Shaw’s comments was predictable and vitriolic. It cost him greatly at the box-office, many of his friends turned against him. He became one of the most despised men in England and it was proposed that he should be tried for treason .

.

Indeed, those men suspected of avoiding their duty were vilified. Street assaults became so common that a Silver War Badge needed to be issued to men who were not eligible or who had been discharged. Suffragettes, in particular, became very enthusiastic patriots. Torquay had a very active women’s suffrage movement with both the Suffragists and the more militant Suffragettes being active in the town. The Suffragettes asked their members to give white feathers – the sign of the coward – to men who appeared to be of military age to shame them into service. One such recipient later in the conflict was the Torquay schoolmaster Arnold Ridley – who would become better known for his role as Private Charles Godfrey in the classic TV series Dad’s Army. That’s Arthur as both a young man and later as most people now remember him.

Arnold had fought for more than a year on the frontline. He went ‘over the top’ at the Battle of the Somme, was wounded three times and suffered from shellshock, blackouts and terrible nightmares for the rest of his life. Yet, In Torquay in 1917 Arnold was handed a white feather by a tall young woman wearing a fox fur. She didn’t realise that he had served with courage, and been stood down from duty. He took it without comment. When he was asked why, he answered: “I wasn’t wearing my soldier’s discharge badge. I didn’t want to advertise the fact that I was a wounded soldier and I used to carry it in my pocket.”

To give an indication of the pressures on men to enlist, here’s the music hall recruiting scene from “Oh! What a lovely war!”

…