“I had a little bird,

Its name was Enza.

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza”

A 1918 children’s skipping rhyme

In 1918 the three towns of the Bay fell victim to the Spanish Flu.

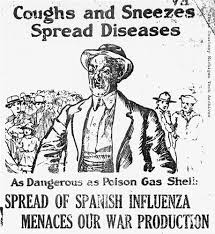

This was no ordinary outbreak, however. Spanish Flu infected 500 million people across the world, from remote Pacific islands to the Arctic. The death rate was 25 times higher than in a normal flu epidemic and between 20 and 40 million people died – 3 to 5% of the world’s population.

The pandemic was one of the worst natural disasters in human history and it killed more people than the Great War. Indeed, more people died of influenza in a single year than in the four years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351. It became known as Spanish Flu as wartime censors had minimised early reports of the illness in Germany, Britain, France, and the United States. As Spain stayed out of the Great War their newspapers weren’t censored, and so it appeared as though Spain was particularly affected.

While usually flu is a killer of the elderly and young children, Spanish Flu was most deadly for people ages 20 to 40. Young adults with the strongest immune systems were the most vulnerable. Those contracting the disease could die rapidly. People on their way to work were reported as suddenly developing the flu and perishing within hours. One anecdote was of four women playing bridge together late into the night. By morning, three of the women had died.

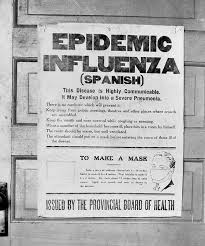

In May of 1918 Glasgow was the first British city to be affected. Within weeks the illness had spread south, reaching London by June. During the next few months, 228,000 people died across Britain.

By July the fu was being reported in the Bay. Brixham’s Deputy Medical Officer noted, “There were a lot of people running around with the Spanish flu epidemic.” By the end of the year 25 people had died in Brixham, with most being women from the 25-45 age group. Brixham’s Medical Officer suggested that women were particularly susceptible as, “they go about with bare chests and other eccentricities of fashion”, such as very thin stockings.

In Torquay the numbers of infected grew. There were 12 deaths between January and July. While August and September were quiet, the disease became epidemic in October with 72 deaths in the last 3 months of the year.

In their report of 1918 Torquay’s health authorities stated: “The disease was of an unusual type. The onset being quickly followed by a toxic form of pneumonia, which was little effected by treatment and rapidly proved fatal. Strong robust individuals and pregnant women nearing the end of their confinement were common victims. In the latter abortion took place, quickly followed by death”.

The pandemic severely disrupted the Bay. Theatres, dance halls, churches and other public-gathering places were shut. Across Devon 516 schools were closed.

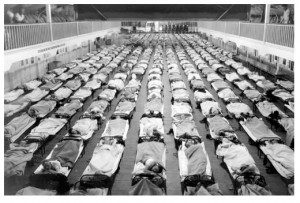

Men in uniform were particularly prone to the flu. Of the American soldiers who died in Europe, half of them fell to the influenza virus and not to the enemy – 43,000 lost their lives. This death toll was reflected in the Bay with over 100 American servicemen dying at the Oldway War Hospital in a fortnight. They were buried in a communal grave on the west side of Paignton Cemetery, but were exhumed in 1920 and taken back to the United States. In October Paignton Council sent a ‘Vote of Condolence to the American Nation, Army and Relatives’ of those fighting men.

Britain’s other allies similarly suffered and the New Zealand soldiers who succumbed after the end of the war lie by their monument in Torquay Cemetery (pictured below).

Eventually, after taking millions of lives across the world, this deadly strain of the flu faded away, though it continued to claim victims through 1920.

We don’t know why the flu virus suddenly mutated into such a deadly form. We also don’t know how to prevent it from happening again. Even today scientists continue to research into the 1918 Spanish Flu in the hope of being able to prevent another worldwide pandemic.