In the 2004 science fiction movie ‘I Robot’ Will Smith states “Robots don’t feel fear. They don’t feel anything. They don’t eat. They don’t sleep. Human beings have dreams. Even dogs have dreams, but not you, you are just a machine. An imitation of life. Can a robot write a symphony? Can a robot turn a canvas into a beautiful masterpiece?”

Sonny, the irritatingly smug robot, replies, “Can you?”

Except now robots can write symphonies.

The London Symphony Orchestra recently performed ‘Transits—Into an Abyss’, a composition created entirely by Iamus, a system designed by the University of Malaga. Here’s a shorter piece by Iamus:

The quest for a machine that can equal humans – and even surpass us – has been going on for years. A significant milestone in this journey came in Philadelphia in 1997 when the IBM supercomputer Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov, the first defeat of a reigning world chess champion to a computer under tournament conditions:

IBM then started actively seeking the next game it could beat humans at. In 2004, researchers chose ‘Jeopardy’, the American quiz show. They entered Watson, a “question answering machine,” and beat the best human representatives we could put forward:

Watson’s machine learning capabilities simulated the human thought process, but it was further built to eliminate the bias and error out of decision-making. Its innovative technologies are now being used to tackle social challenges such as improving health care, education and the environment. It’s been incorporated into abound 17 different industries and IBM is working with more than 500 partners to build Watson’s cognitive applications, such as in retail, law, image recognition, and even cooking and catering.

This is just one example of how computers are advancing. It’s the ongoing fulfilment of Moore’s Law, a computing term which originated around 1970 – the simplified version states that overall processing power for computers will double every two years.

This is just one example of how computers are advancing. It’s the ongoing fulfilment of Moore’s Law, a computing term which originated around 1970 – the simplified version states that overall processing power for computers will double every two years.

Of course, this advance of the machines may not all be good news. We used to accept that some routine, boring and low paid jobs would be replaced by computers and robots. Hence, workers in transport and logistics (such as taxi and delivery drivers) and office support (such as receptionists and security guards) are likely to be substituted by computers, along with sales and services (such as cashiers, counter and rental clerks, telemarketers and accountants). The figure suggested is that 35% of the British workforce could be vulnerable to being replaced by technology. At this stage what determined vulnerability to automation was not so much whether the work concerned was manual or white-collar but whether or not it was routine.

It was believed that we would consequently see job polarisation, where middle-skill jobs (such as those in manufacturing) would decline but both low-skill and high-skill jobs would increase. The workforce would subsequently split into two groups. One group would carry out non-routine work: highly paid, skilled workers (such as architects and senior managers). The other would consist of low-paid unskilled workers (such as cleaners and care workers). Our current stagnation of wages is then evidence of creeping automation – though it is made more complicated by off shoring where many routine jobs (including manufacturing and call-centre work) were relocated to low-wage countries… at least at first.

But now there’s concern that automation is becoming blind to the colour of our collars, whether they are white or blue, routing or skilled. If are undergoing a massive skills transfer from humans to machines, we could be seeing the beginnings of a jobless future as most jobs can be broken down into a series of routine tasks, more and more of which can be done by machines. This process of outsourcing our jobs to machines is happening now. Look at the move to self-driving cars. First came power steering, then cruise control, then automatic parking, auto safety-braking, perimeter detection, and then co-piloting. It won’t be that long until we won’t even notice that many vehicles in the Bay don’t even have a human in them.

But now there’s concern that automation is becoming blind to the colour of our collars, whether they are white or blue, routing or skilled. If are undergoing a massive skills transfer from humans to machines, we could be seeing the beginnings of a jobless future as most jobs can be broken down into a series of routine tasks, more and more of which can be done by machines. This process of outsourcing our jobs to machines is happening now. Look at the move to self-driving cars. First came power steering, then cruise control, then automatic parking, auto safety-braking, perimeter detection, and then co-piloting. It won’t be that long until we won’t even notice that many vehicles in the Bay don’t even have a human in them.

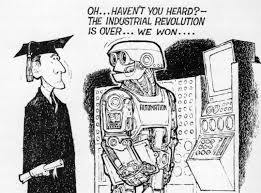

On the other hand, predictions that automation will make humans redundant aren’t new. During the Industrial Revolution, textile workers such as the Luddites protested that machines and steam engines would destroy their livelihoods – “Never until now did human invention devise such expedients for dispensing with the labour of the poor,” said a pamphlet at the time. In the 1930s John Maynard Keynes wrote of “technological unemployment” while in 1964 a group of Nobel prize-winners warned US President Lyndon Johnson of a revolution triggered by “the combination of the computer and the automated self-regulating machine”. This would lead to a new era “which requires progressively less human labour” and there would be a society divided into a skilled elite and an unskilled underclass. It didn’t happen… at least it hasn’t happened yet.

On the other hand, predictions that automation will make humans redundant aren’t new. During the Industrial Revolution, textile workers such as the Luddites protested that machines and steam engines would destroy their livelihoods – “Never until now did human invention devise such expedients for dispensing with the labour of the poor,” said a pamphlet at the time. In the 1930s John Maynard Keynes wrote of “technological unemployment” while in 1964 a group of Nobel prize-winners warned US President Lyndon Johnson of a revolution triggered by “the combination of the computer and the automated self-regulating machine”. This would lead to a new era “which requires progressively less human labour” and there would be a society divided into a skilled elite and an unskilled underclass. It didn’t happen… at least it hasn’t happened yet.

Indeed, some jobs will probably always be better performed by humans, particularly those requiring social interaction, such as doctors, therapists, hairdressers and personal trainers. And these are the jobs that are increasing in number. The consultancy Deloitte found over the past two decades that there had been a shift towards ‘caring’ jobs in Britain. The number of nursing assistants increased by 909%, teaching assistants by 580% and care workers by 168%. Yet, these are the jobs that are often poorly paid, can have unsocial hours and many require a degree of physical fitness.

Indeed, some jobs will probably always be better performed by humans, particularly those requiring social interaction, such as doctors, therapists, hairdressers and personal trainers. And these are the jobs that are increasing in number. The consultancy Deloitte found over the past two decades that there had been a shift towards ‘caring’ jobs in Britain. The number of nursing assistants increased by 909%, teaching assistants by 580% and care workers by 168%. Yet, these are the jobs that are often poorly paid, can have unsocial hours and many require a degree of physical fitness.

We used to think that at least we humans were unique in our creative abilities. Yet already newspapers, web sites and companies are replacing human writers with computers producing stories that are pretty much indistinguishable from human written ones, especially for sports and finance.

Here’s another frontier that may soon be breached. Humans may imminently be outclassed by robots in creating original music. Already some of our most popular artists don’t play any instruments or even sing and for years there’s been a separation between creation and performance. Stadiums are full of people paying to watch a computer being operated by a man in headphones. With digital processing, much music is already inorganic, it’s made in the studio, enhanced by engineers and producers. The next step will be computers composing and writing song lyrics – so eliminating expensive humans and raising profits. They can produce pieces of music in minutes and can harvest data to create a piece of music to suit an individual’s specific tastes based on Facebook posts, past CD buying, concert going, emails and other interactions. At the moment we can still tell if it’s a computer that’s doing the actual singing. One day soon it may be impossible to tell… and will we even care?

Here’s another frontier that may soon be breached. Humans may imminently be outclassed by robots in creating original music. Already some of our most popular artists don’t play any instruments or even sing and for years there’s been a separation between creation and performance. Stadiums are full of people paying to watch a computer being operated by a man in headphones. With digital processing, much music is already inorganic, it’s made in the studio, enhanced by engineers and producers. The next step will be computers composing and writing song lyrics – so eliminating expensive humans and raising profits. They can produce pieces of music in minutes and can harvest data to create a piece of music to suit an individual’s specific tastes based on Facebook posts, past CD buying, concert going, emails and other interactions. At the moment we can still tell if it’s a computer that’s doing the actual singing. One day soon it may be impossible to tell… and will we even care?

In 1958, John von Neumann imagined ‘the singularity’ to be the moment artificial intelligence becomes self-improving and self-aware. It’s said by some that that will be the moment that people become pets.

… or will we always need a human hidden somewhere in the machine to keep pulling the strings: