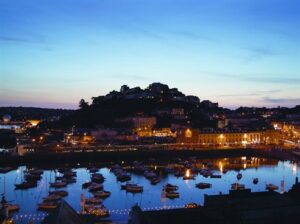

The growing challenge to Torquay’s status as an elite tourist destination was becoming evident from the mid-1960s onward, with the far-sighted recognising the overseas package holiday as an existential threat. On the other hand, though the nature of the British vacation was clearly changing and was becoming increasingly noticeable, the town had faced similar challenges over the past 150 years in times of recession and war.

To fill the gaps in trade and visitors, solutions both old and new were sought by business owners and the authorities. For some this was to be found the time-honoured replication of the image and success of the continental Rivieras; while cautiously embracing the modern and briefly fashionable.

This was the old conflict, to remain upmarket, or to cater for the spending power of masses; twin, and often contradictory, drivers in the commercial need to attract tourists, but a simultaneous resistance to unregulated outside influences that might bring disorder and moral upheavals.

Economic pressures and opportunities could be most apparent on the Harbourside in new ventures, demolition of the old and construction of the new.

Known across the nation, this commercial and entertainment hub would eventually be transformed into the epicentre of Torbaydos, the location of many decades of young men skirmishing, the grease and glitter of the arcades, pavement pizzas, stags and hens, mass-produced fancy dress, all alongside the lost and the lonely.

This was partly the consequence of a generational shift in the town’s visitors as the young became more affluent and able to travel. The resort attracted the young to a place that retained its glamour, but which was also in the reach of those with limited resources. In July 1976 a local reporter eulogized about The Yacht,

“It’s the height of the summer season in Torquay and lads from all over Britain are bevying it up in the long dark music bar. The girls are with them, indistinguishable with their long hair hanging over sweat shirts and faded jeans. This is Torquay’s most notorious public house which attracts the wild, the youthful and the unemployed. At a time of year when Torquay is one of the ‘in’ towns in the country, the Yacht is the ‘innest’ place of all.”

Underlying this change was a clash between enduring values and principles, and short-term economic realities, indicated in behaviour, language, architecture, industry, cultural form and artistic representation. These disputes could erupt over emblematic issues based on divergent interests, manifested in tensions between residents, guest house owners and the larger hotels.

Locally-filmed movies picked up on such social change and exaggerated the stereotype of a conservative older generation versus rebellious youth.

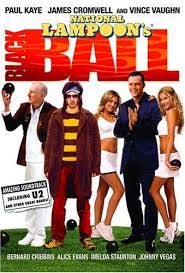

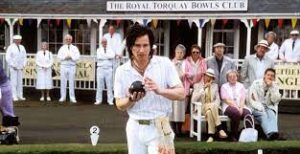

In the 2003 movie ‘Blackball’, Cliff Starkey (played by Paul Kaye) is a rebellious young bowls player whose dream is to play for his country. However his behaviour gets him banned from the bowls club for 15 years. Picked up by a sports agent (Vince Vaughn), Starkey is re-branded as the “bad boy of bowls”, turning the normally sedate sport into a glitzy competition.

James Cromwell plays the blazer-wearing personification of the town’s conservative traditions, a veteran player being challenged by the representative of a new irreverent generation. Noticeably, the Pavilion symbolises the Bowls Club’s establishment’s pretentions and long traditions, while Starkey is seen practicing in a local housing estate.

Although the plot is fictional, the central character was based on real-life local bowls player Griff Sanders.

Blackball was filmed in Torquay (the Bowls Club and the Pavilion) and the Isle of Man during October and November 2002.

As a bit of trivia, to appeal to an American audience, the movie was known as ‘National Lampoon’s Blackball’ in the States’. This may have been a bit of a surprise for an Arkansas movie-going audience expecting to see Chevy Chase:

And here’s the trailer: