We’ve long been worried about youth crime.

Evidence from the courts and newspaper articles suggests that juvenile crime really was a problem. During the late 1700s there was a decline in apprenticeships and new types of industry disrupted family life. Petty crime among children further increased at the beginning of the nineteenth century as people moved to the towns and cities searching for work. Unemployment led to desperate poverty and overcrowding and squalor in the growing slums of towns such as Torquay.

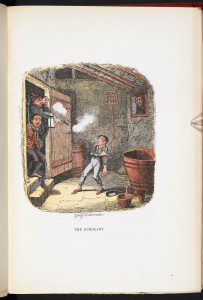

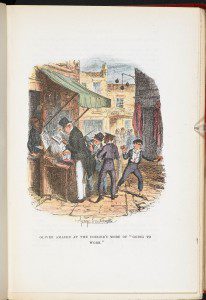

Sensational stories of the activities of criminal gangs of boys and girls filled the pages of the popular press. These were often about bosses who supposedly trained young boys to steal. These ‘lads-men’ often worked from ‘flash-houses’, pubs or lodging houses where stolen property was ‘fenced’. Picking of pockets was especially common, particularly the theft of silk handkerchiefs, which had a high resale value and could be easily sold. Crowded places such as fairs, marketplaces and public executions were particularly profitable for young thieves.

Sensational stories of the activities of criminal gangs of boys and girls filled the pages of the popular press. These were often about bosses who supposedly trained young boys to steal. These ‘lads-men’ often worked from ‘flash-houses’, pubs or lodging houses where stolen property was ‘fenced’. Picking of pockets was especially common, particularly the theft of silk handkerchiefs, which had a high resale value and could be easily sold. Crowded places such as fairs, marketplaces and public executions were particularly profitable for young thieves.

After 1800 children between the ages of seven and fourteen were considered incapable of forming criminal intentions, but could nevertheless be found guilty and severely punished.

The punishment options used to deal with child criminals were mostly transportation, imprisonment or flogging. There were death sentences imposed on children but these were almost always commuted to lesser sentences – of the 103 children aged 14 or under who were sentenced to death at the Old Bailey between 1801 and 1836, not one was executed. Usually children were, “recommended to mercy on account of their youth” and death sentences for girls and boys under 16 years of age were usually commuted to transportation. By the 1830s, each year around 5,000 prisoners, some as young as 10, were carried by ship to penal colonies in Australia, to serve sentences of seven years, fourteen years or occasionally life. Transportation was finally abolished in 1857 following doubts about the deterrent effect of the sentence on would-be criminals.

The punishment options used to deal with child criminals were mostly transportation, imprisonment or flogging. There were death sentences imposed on children but these were almost always commuted to lesser sentences – of the 103 children aged 14 or under who were sentenced to death at the Old Bailey between 1801 and 1836, not one was executed. Usually children were, “recommended to mercy on account of their youth” and death sentences for girls and boys under 16 years of age were usually commuted to transportation. By the 1830s, each year around 5,000 prisoners, some as young as 10, were carried by ship to penal colonies in Australia, to serve sentences of seven years, fourteen years or occasionally life. Transportation was finally abolished in 1857 following doubts about the deterrent effect of the sentence on would-be criminals.

Imprisonment was the usual punishment and children served lengthy prison sentences, normally alongside hardened adult offenders – eight year old Sarah Ann Franks, for instance, was sentenced to three months in 1857 for stealing peppermints. There were only a few children under the age of ten in prison, however, though the number of those in jail aged more than ten increased steeply.

In 1888 Charlotte Higgins, a 14-year-old domestic servant, was arrested in St Marychurch. She had sent threatening letters, supposedly written by Jack the Ripper, to her employer the Rev Samuel Harvey, a retired clergyman living at a house called Holmdene. One threatened, “My God I’ll cut you up from head to foot; I’m the Whitechapel Murderer.” Eventually Charlotte confessed and was sent to prison for three weeks, and then to a reformatory for three years. Yet, it’s interesting that many locals saw the sentence as disproportionate: “The decision of the Bench was received with loud hisses by the public in the body of the Court.”

In 1888 Charlotte Higgins, a 14-year-old domestic servant, was arrested in St Marychurch. She had sent threatening letters, supposedly written by Jack the Ripper, to her employer the Rev Samuel Harvey, a retired clergyman living at a house called Holmdene. One threatened, “My God I’ll cut you up from head to foot; I’m the Whitechapel Murderer.” Eventually Charlotte confessed and was sent to prison for three weeks, and then to a reformatory for three years. Yet, it’s interesting that many locals saw the sentence as disproportionate: “The decision of the Bench was received with loud hisses by the public in the body of the Court.”

In England all criminals were thrown together in the common jail regardless of crime or age. It wasn’t until 1823 that laws were introduced that provided separate lock-ups for those awaiting trial and convicted and hardened criminals. It was also recognized that a distinction should be made between the habitual and the casual criminal and so separate prisons were designated. On the other hand, it wasn’t until the Children Act of 1908 that imprisonment for children under fourteen was abolished.

In England all criminals were thrown together in the common jail regardless of crime or age. It wasn’t until 1823 that laws were introduced that provided separate lock-ups for those awaiting trial and convicted and hardened criminals. It was also recognized that a distinction should be made between the habitual and the casual criminal and so separate prisons were designated. On the other hand, it wasn’t until the Children Act of 1908 that imprisonment for children under fourteen was abolished.

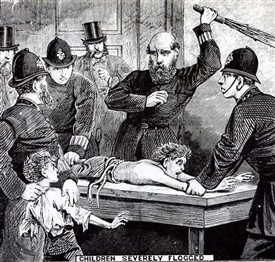

The most common punishment for children was whipping or flogging which was frequently used until the end of the nineteenth century. Whippings could be carried out quickly after guilty sentences were passed in court, or in prisons as part of custodial sentences. There was, however, some criticism of such harsh penalties. According to a former magistrate in the 1860s, the whipping of boys at London’s Bow Street magistrates’ court was finally abandoned as “the screams of the boys” caused “angry excitement” among nearby residents.

Nevertheless, despite concerns over the severity of punishments, they continued. In 1941 Torquay’s court records were pulped as part of the war effort. Before they were destroyed, however, some of the reports were copied. Here’s a few from around 1850 relating to Torquay’s young offenders.

Nevertheless, despite concerns over the severity of punishments, they continued. In 1941 Torquay’s court records were pulped as part of the war effort. Before they were destroyed, however, some of the reports were copied. Here’s a few from around 1850 relating to Torquay’s young offenders.

Stephen S, aged 13, was given “12 stripes” (flogged) for stealing a tin of biscuits, value one shilling.

Matthew R, aged 14, received three weeks hard labour for stealing strawberries from a Torquay garden.

An application was received from Mary Ann D to have her 12 years old son sent to an industrial school. She said she was dying, and her son was getting beyond her control and, “consequently getting into bad ways and associating with bad boys”. Her application was granted.

Three boys, aged 12, 11 and 10, were found guilty of cutting the hair from horses’ tails in a stable in Temperance Street and selling it. The oldest two were each given, “12 stripes and to be confined in a reformatory until the age of 16″. The youngest received 12 stripes.

Notably the above cases mostly involved boys and often the need to acquire food. Girls had other options to avoid starvation and the horror and shame of life in Newton Abbot’s Workhouse. While estimates of the number of prostitutes in Victorian England differ, a nineteenth century town commonly had 1 prostitute per 36 inhabitants, or 1 per 12 adult males. If we take the above ratios, this would give us over 700 Torquay prostitutes. Even at half this number, prostitutes – many being very young – would have been a significant presence in our town. Victorian Torquay could be a very hard place for a working class child to grow up.

For more community news and info, join us on Facebook: We Are South Devon or Twitter: @wearesouthdevon