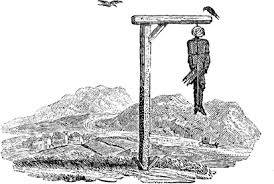

“Executions are intended to draw spectators. If they don’t draw spectators, they don’t answer their purpose”,

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)

Death by hanging was the main form of execution in Britain from Anglo-Saxon times until capital punishment was suspended in 1964. For centuries, public executions were one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Britain, all hangings being carried out in public. Hence, gallows were often sited in open spaces to accommodate large crowds. They were located at the edges of towns, by roads, or on hilltops where victims could be seen. Executions showed the power of justice – the French word for gallows, ‘potence’, comes from the Latin word potentia, meaning ‘power’. Executions had real importance to local communities. After corpses were cut down, for example, there was often a rush to grab the bodies, as some believed their hair and body parts could heal illnesses.

The site for public executions for those communities which now make up Torquay is Gallows Gate. It’s just by the roundabout at the top of Hamelin Way on the A380. At around 495 feet above sea level, the site is on an ancient ridge way and where the four parishes of Cockington, Marldon, Kingskerswell and St Marychurch meet. In 1436 the Cockington Manor Court referred to a ‘stope’, usually defined as a gibbet or whipping post which could be at Gallows Gate. A Marldon Tithe Map of 1839 shows a three-cornered field called Gallows Gate Field.

To the south is Dada Croft – the similar sounding ‘daudaz’ is Saxon for ‘dead’, so it’s reasonable to see the small enclosed field as a place reserved for the remains of those who died in the immediate area. It’s generally thought, however, that the original site of the gallows was 170 meters to the north of Gallows Gate, at Kingsland, the highest point and where the reservoir now is. One suggestion is that the gallows were moved in the 1820s when public opinion began to turn against disorderly public hangings and the suspended rotting corpses which could be seen for miles around.

It wasn’t until the Prisons Act of 1868 that executions had to take place within prison walls. Our offenders then ended their lives at Exeter Prison where hangings took place in a purpose-built execution shed. Yet, even with the more professional ‘long-drop’ mistakes were made – notably in the failed attempts to execute John Babbacombe Lee in February 1885!

Our place for terminal justice has a very long history. The Haytor Hundred is recorded as being held at Kingsland (the King’s Land). This would have seen gatherings of men called to fight and hold open air courts, as well as providing a good lookout for sighting hostile ships in the Bay. The partition of Devon into Hundreds dates from King Alfred (871-901) and so this could mean that Gallows Gate served for well over a thousand years as a place of execution.

It’s worth noting how widely the death penalty was used in medieval and early modern England, before the development of the prison system. During the reign of Henry VIII, for example, 72,000 people are estimated to have been executed. By 1820, there were 160 crimes punishable by death, including shoplifting, petty theft, and cutting down trees.

Gallows Gate also had a gibbet, where executed criminals could be left to rot. Up to the late seventeenth century, live gibbeting also took place, in which the criminal was placed in a metal cage and left to die of thirst. Such gibbeting became common in the mid-eighteenth century due to a perceived increase in murders, and was regularised in England by the Murder Act 1752. This Act stipulated that “in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried”, the cadaver was either to be publicly dissected or left “hanging in chains”. The practice ended in 1832 but it took a few decades before the last gibbet was removed.

As murderers and suicides were denied Christian burial, the unconsecrated burial grounds near execution sites were prime candidates for ghosts and were avoided at night. To avoid any rising of the dead, bodies were often dismembered and buried with a wooden stake driven through the remains and left sticking out of the ground as a warning. An Act of Parliament finally prohibited staking in 1823.

There’s further evidence that Gallows Gate was an ancient site of significance for local people. There’s an old gate along with a plaque which tells the legend of a man who stole a sheep which he tried to carry away slung by a rope on his back. In getting over a high gate, the carcase fell on side and the thief the other – the stolen sheep hanged the thief. The gate remains to commemorate the legend.

However, variants of the same story can be found in other places. In Devon alone there are nine, with five of these found on Dartmoor. The difference is that, instead of a gate, the rope is caught around a rock – hence the ‘hanging stones’ across the Moor. The story seems to reflect the importance of sheep farming. In 1741 a law specifically defined the death penalty for sheep stealing. Across Britain hanging stones are to be found on parish boundaries and are often associated with nearby gallows.

Therefore, one possibility is that there may have been standing stones at Gallows Gate. In an inventory of 1654, the area was known as Stauntor, Stontor or Stantor, meaning ‘stone hill or eminence’. This could indicate that the original site had a monolith or “some such monument to a prehistoric chieftain”. We know the Anglo-Saxons used old burial mounds and Bronze Age sites as places for the execution of criminals who were removed from villages to places associated with ghosts and demons. In July 1964, and again in early 1965, deep chasms appeared near the summit of Kingsland Hill. The Water Board investigated and found two passages 12 meters below the surface and several hundred meters long. Fragments of bone and wood were found, indicating that at one time the pits were open. There’s also a Neolithic chambered tomb not too far away at Broadsands.

So, along with Gallows Gate being a place of execution, it also appears to have been important for other purposes. Over its long history, thousands of people would have lost their lives in this unnoticed plot of land by the side of one of the Bay’s busiest roads. It’s an intriguing suggestion that this intersection of four parishes has been significant for local people since prehistoric times.