“The time of childhood is not the time for labour, but growth, for development, mental, physical, moral and spiritual.” The Torquay Child Labour Deputation of 1900.

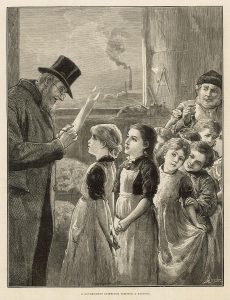

(The photo is of Torquay’s Pimlico in 1900)

In his 1901 study ‘Poverty: a Study of Town Life’, B. Seebohm Rowntree argued that there was a family life cycle. A married couple might start off in relative prosperity, but once the children started arriving the family would enter a trough of poverty. They would emerge from poverty only when a sufficient number of the children were earning. Then, when the children left home and the parents’ earning potential was reduced, there would be another trough of poverty lasting through old age to death.

The important issue here is that children were expected to contribute to the household – they were the way to avoid poverty or even starvation. If they didn’t, or couldn’t, work they were a burden which would endanger the entire family. Hence, the large numbers of unwanted or disabled children that were killed at birth – such as those murdered by Torquay’s baby farmer Charlotte Winsor. Before the early twentieth century children had always worked, with their access to work being regulated by their strength and ability.

During the 19th century working-class children were often employed in factories and on farms – for many families, it was more important for a child to bring home a wage than to get an education. The combination of dangerous working conditions and long hours meant that children were worked as hard as any adult, but without laws to protect them. They were cheaper to employ than adults, and easier to discipline.

In 1840 Lord Ashley, set up the Children’s Employment Commission, interviewing hundreds of children in coalmines, works and factories. Its findings caused great concern, but sometimes not in the ways we may expect.

Many people had no idea that coal was excavated by young children. But, for many, it was the immorality rather than the cruelty that shocked them most. An inspector described how in coal mines, “the chain (used to pull the carts) passing high up between the legs of two girls, had worn large holes in their trousers. Any sight more disgustingly indecent or revolting can scarcely be imagined. No brothel can beat it.”

An Act was passed, prohibiting women and children under ten from working underground. Two years later, a further Act was passed prohibiting the textile industry from employing children under the age of nine. But it wasn’t until the mid-19th century that children were limited to a 12-hour day. Subsequent laws raised their age and made working conditions safer.

In 1880, the Compulsory Education Act helped reduced the numbers of child labourers. The Education Act brought significant changes. It put in place a free and compulsory education system and gradually every child in Britain was introduced to schooling. By the late 19th century, children’s lives were beginning to be transformed. They were going to school instead of work, and being treated as children instead of ‘little adults’.

Children at work became a political and social issue – the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) was founded in 1889 and more became known about child labour. In 1899 the government asked for a report from the 23,000 national and board schools. About 9,000 schools sent in reports: 39,000 children had to work 10 hours a week; 60,000 10-20 hours; 27,000 21-30 hours; 9,000 31-40 hours; and 2,390 41-50 hours. The total number of working school age children was 144,026.

Specific legation was brought in. The Mines (Prohibition of Child Labour Underground) Act 1900 prevented boys under the age of thirteen from working in an underground mine. Around 3,000 boys were affected. By 1900, the Board of Education wanted all children to stay on at school until the age of 14, but the majority still left at 13 or even 12 to start manual labouring jobs.

Although labour and schooling legislation was difficult to enforce, by the early twentieth century children’s work was mostly part-time up to the time they left school. When they did leave school, they were much more likely to find work as messengers, shop assistants, or domestic servants than as factory or mine workers. The labour market had become segregated with certain types of work seen as belonging to children who were now on the margins of the economy, rather than at its centre.

Yet, there were still many children that worked long hours.

In 1900 a deputation on the matter of child labour visited Torquay Council. It was led by local churchmen including ministers from Upton and St Luke’s. They raised the issue of, “children at a very early age subjected to heavy and laborious work, and more particularly to the late hours at which they were employed”.

The deputation gave examples of newspaper boys, employed between 8-9 in the morning, then between 12-2 and again 4-10 in the evening, and almost all day on Saturday. When the members visited a Torquay school they found two boys asleep in class, only with difficulty could they be woken.

Torquay’s Sunday Schools reported that boys were coming in at 10 in the morning and “within 45 minutes they had bowed their heads and were fast asleep on their form.” Their teachers said they were “dead beat”.

More investigation was needed and it was revealed that in the Torquay National School there were 8 boys who were working 7 hours per day. The boys were further employed the whole of Saturday until 10 at night. This amounted to 50 hours a week outside of the school curriculum.

The Chief Officer of the Coastguard was also interviewed. He had rejected for service around half of the Torquay boys who had applied – they had bad teeth or poor eye sight, while a third suffered from varicose veins. The investigators believed that the varicose veins were caused by long standing and strain.

It was stated that at 7 in the morning boys of 11, 12 and 13 could be seen “trudging along with milk cans of 100lbs in weight”. The most these boys could earn was 1 shilling and sixpence for 50 hours work. Even though the law said that no child under 11 should be allowed to trade in the street, there were “large numbers of boys selling newspapers in the streets of Torquay under that age”.

Responding to the deputation, the Mayor agreed that child labour was, “an evil which cried aloud for attention”. However, he also admitted that, “The matter was beyond the power of the Council or magistrates and it was to public opinion they must appeal.”

Nevertheless, the Mayor, Councillor Beavis, did take a case to the Torquay police court and the NSPCC later that same year. He reported that, “at his door appeared a poor little boy who came with a parcel.” The boy had “twenty or thirty newspapers under his arm. The child was a frail, attenuated, anaemic little fellow. He was ten years old, but looked more like eight. His clothes indicated poverty, and he had scarcely any boots to his feet.”

The Mayor was, “astounded that any newspaper office should employ such a poor wretched specimen of humanity to trudge about the Torquay hills with newspapers. He was so weak and frail that he could hardly crawl up the hill to the Mayor’s house. He understood that the father was a drunken reprobate, who pretended to be out of work.”

Gradually, the campaign against child labour gained ground and the school leaving age was increased. The 1918 Fisher Act brought in a standard leaving age for all of 14, against opposition from some employers and many parents. In 1947 the leaving age of 15 was implemented and in 1972 compulsory schooling was raised to 16.