On February 4, 1931 the Torquay Directory told of a ‘gang’ that had “terrorised the neighbourhood” of Babbacombe.

The same issue reported on another gangster called Al Capone who was similarly “terrorising” the citizens of Chicago.

The newspaper wasn’t that clear what the gang had been up to, though they did relate an incident where, “One resident fell a victim of this malign gang, was subjected to an outrageous attack in the dead of night, while he was in bed, his house was ‘stoned’, and his front door badly damaged”.

Whatever else the gang had been up to, the paper declined to be specific, and used the general term “evil activities”. In response, “The Police had already been called in and from time to time have captured some of the members”.

However, the authorities wanted to prevent the situation from deteriorating further and sent in a plain clothes police officer to scour the streets in search of the evil-doers. The officer selected was a PC Gammon. (Incidentally, the name of this particular officer may have even caused some amusement amongst juvenile readers of the Torquay Directory way back in 1931. The derogatory term for policemen was commonly used during the 19th century. Though it did fade from use during the 20th century, it came back into fashion in the 1960s.)

On Sunday, January 25 PC Gammon tracked the gang down to Victoria Park Road. According to reports, “He saw the entire gang playing football in the roadway. As he went towards them, one of them suspected his identity and shouted to his comrades ‘Look out. Policeman!’ It was too late, however, the entire gang, seven in number, were caught red-handed. One of their number was inclined at first to be defiant and he exclaimed ‘Me! All right, we’ll see about that’.”

At Torquay Police Court the miscreants pleaded guilty to playing football in the roadway. The seven young men, who were described as being “employed as caddies and errand boys”, were fined heavily, at around a week’s wages each. The Magistrate warned them that they would not get off as lightly next time and promised them that, “We are not going to have Babbacombe turned into a hooligan’s preserve.”

Torquay Police were delighted at their gang-busting operation, “From the Police point of view, it was undoubtedly the most successful round-up since the gang have been in existence.” Indeed, in comparison, it took over 10 years for the Chicago Police to convict Al Capone. However, their joy was short-lived. It was revealed that, rather than there being a single ‘Babbacombe Gang’ which had been causing mayhem, there were two rival gangs: The ‘Babbacombe Gang’ and the ‘Plainmoor Gang’. The police had smashed the Plainmoor Gang, leaving their Babbacombe opponents “laughing”. Whether “those Babbacombe Lads”, as the Directory called them, went on to further street-football outrages isn’t known.

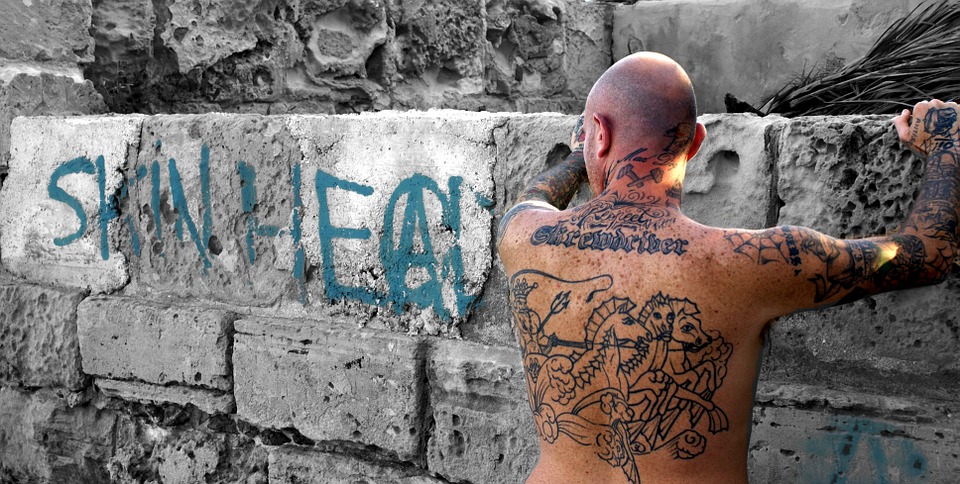

Forty years later, Torquay faced further threats from rebellious young people. First from Mods and Rockers, and then from another youth cult. While Mods were known for their devotion to fashion, music and scooters, some Mods with less disposable income resorted to practical clothing that suited their lifestyle: boots, jeans and T-shirts. It’s said that, in around 1965, a split developed between the peacock, or smooth, Mods and the hard Mods. The hard Mods could be identified by their shorter hair and more working class image. By 1968 these hard Mods became known as Skinheads.

Since May 1964, when Mods and Rockers started the tradition of rioting in south coast resort towns, Bank Holidays had the potential for trouble. Yet, unlike Brighton or Bournemouth, which were an easy scooter or motorbike ride from London, Torquay was generally too much of a trip for the new ‘folk devils’ of popular culture. However, Bristol and Plymouth were only a few hours by train.

In 1970 Richard Allen’s Youthsploitation novel ‘Skinhead’ had been published, “a story straight from today’s headlines – portraying with horrifying vividness all the terror and brutality that has become the trademark of these vicious teenage malcontents.”

Now Skinheads had a script to work to.

Torquay had its first experience of Skinheads on the Easter weekend of 1970. The Torquay Times wrote of the arrival of these, “followers of the latest teenage cult of violence… This weekend’s invasion of the crop haired youngsters dressed in their adopted style of jeans, heavy boots and sporting near-shaven heads, first caused trouble on inbound trains on Good Friday. Carriages were damaged and passengers complained to British Railway police who were called to quite down the troublemakers, believed to come from the Bristol area. During the weekend there were occasional scuffles along the sea front as lines of chanting teenagers linked arms across the road and halted traffic.”

On Easter Sunday a car was rolled into the sea from North Quay, and fittings on some boats were damaged. Yet, the police seemed to see this as a one-off. Chief Supt CJ Tarr told journalists, “We will not tolerate this type of behaviour. This is the first time that this particular group of youngsters have caused disturbances and I cannot see there is any need to worry about a repeat of it during other holiday weekends.”

However, the weekend violence became a regular event in tourist resorts throughout the country and, by August, the Skinheads found someone to fight with, “During last Sunday’s rampage by Hells Angels and Skinheads, a crowd of 200 on Torquay seafront scuffled with police – and a Newton Abbot man trying to telephone an ambulance was dragged out and beaten.”

Not for the last time in the town’s history, a local taxi driver summed up the reaction of the tourist industry, “If Torquay gets a reputation for this sort of thing, it will kill the area as a holiday resort. Many of the youngsters act like wild animals. They need a real lesson – not a couple of quid fine.”