The science-fiction writer William Gibson said, “The future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed yet.”

William has a point. Things are changing in Torbay and they’re changing quickly. Take a trip to ASDA or Sainsbury’s and see the rising number of self-service checkouts; ask yourself whether you get your cash from the person behind the counter rather than a hole-in-the-wall? Who buys a local newspaper anymore when its ‘news’ is often a week old? Whatever happened to those Lymington Road petrol station attendants? When was the last time you bought insurance or a book from a real human being in a Union Street shop? All these innovations are a sign of technology replacing the jobs local people did just a few years ago.

The Bay’s supermarkets and banks have already decided that it’s more cost effective to use workers that don’t have much training, but instead to build productivity into their systems. Admittedly, these systems have weaknesses – “Item in bagging area is not recognised”, for example, – but they’re improving all the time and it’s just the beginning. According to Oxford University economists Dr Carl Frey, 40% of all jobs are at risk of being lost to computers in the next two decades. As machines, software and robots become more sophisticated and learn to mimic what we do, gradually more and more types of employment will be susceptible to automation. Biotech, infotech, nanotech, energy, healthcare and education are all evolving quickly.

Across the Bay we could lose thousands of jobs. Take driving as a local career, including those driving taxis, busses and white vans. Unlike many other jobs that have declined in recent years, the job has largely remained immune to the forces that have replaced others. Now Google, Uber and Tesla are all working on self-driving vehicles, beginning with those that make long-haul journeys. Think Johnny Cab from the 1990 movie ‘Total Recall’

Across the Bay we could lose thousands of jobs. Take driving as a local career, including those driving taxis, busses and white vans. Unlike many other jobs that have declined in recent years, the job has largely remained immune to the forces that have replaced others. Now Google, Uber and Tesla are all working on self-driving vehicles, beginning with those that make long-haul journeys. Think Johnny Cab from the 1990 movie ‘Total Recall’

Or how about ‘Hadrian’, the fully automated bricklaying machine that, it’s claimed, can build an entire house in just two days. A robotic ‘hand’ applies mortar, lays the brick, and can 3D scan its surroundings to work out exactly where to build. Its Australian inventor asserts it lay 1,000 bricks an hour and work 24 hours a day. Will we soon see the day when the infilling between Torbay and Newton Abbot is being eerily done without the need for local workers?

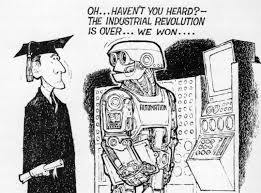

Change is inevitable, but we’ve never before seen it happen so quickly. The Agricultural Revolution took 2,000 years, the Industrial Revolution took 200 years, but this new Computer Age could take 20 years. This can have real implications for those working in their part of a declining system – for example, 22% of employment was in agriculture and fishing in 1840, now it’s 1%.

This may not be a bad thing for many. A recent survey found that more than a third of workers hate their job, with one in ten saying choosing the wrong career is their biggest regret.

So we could be looking at a time in the not-so-distant future when machines do most of the jobs we’re doing today, and humans don’t have to work a whole lot if they don’t want to. Machines will do more of the dirty, repetitive, routine jobs. It’s happened before. Torquay had around 500 villas which needed a labour force to run, which is why in 1900 there were around 20% more women in than men. Washing machines transformed clothes cleaning from an hours-long task into something sorted with the push of a button; power tools made DIY immensely more efficient; and computers eliminated labour-intensive, by-hand calculations and writing. Improvements in our quality of life and health and safety often accompanied these developments, while Torquay’s servile class found other jobs.

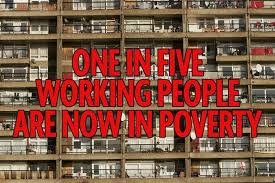

Of course, this is the optimistic view. You can equally argue from a pessimistic standpoint. The whole move to the industrial age actually came with a great deal of pain and disruption. Now, many workers are currently not directly benefiting from technology as we’re not creating enough good replacement jobs. As industrial-era assembly-line jobs fell to the advance of the machine, the traditional working class of the 20th century was in danger of extinction. Certainly, a number of replacement jobs were created, but a very large number of people were pushed down into lower-income brackets. The academic and writer Guy Standing coined the term “precariat”, which described a precarious workforce that learned to expect lower wages, minimal pensions, less job security, poor housing and general insecurity. When whole communities suffered economic disruption and psychological and cultural breakdown, it caused depression, crime, alcohol and drug abuse, and mental-health problems. And when a large percentage of young people think they don’t have a future, that usually leads to civil instability.

Of course, this is the optimistic view. You can equally argue from a pessimistic standpoint. The whole move to the industrial age actually came with a great deal of pain and disruption. Now, many workers are currently not directly benefiting from technology as we’re not creating enough good replacement jobs. As industrial-era assembly-line jobs fell to the advance of the machine, the traditional working class of the 20th century was in danger of extinction. Certainly, a number of replacement jobs were created, but a very large number of people were pushed down into lower-income brackets. The academic and writer Guy Standing coined the term “precariat”, which described a precarious workforce that learned to expect lower wages, minimal pensions, less job security, poor housing and general insecurity. When whole communities suffered economic disruption and psychological and cultural breakdown, it caused depression, crime, alcohol and drug abuse, and mental-health problems. And when a large percentage of young people think they don’t have a future, that usually leads to civil instability.

So far – with the possible exception of Nortel – Torbay hasn’t faced a large-scale loss of well-paid jobs, so local people haven’t seen the collapse in life opportunities that other communities have experienced. Yet, what happens if some of us expecting a decent lifestyle find our aspirations dashed? What we do know is that Torbay has a higher proportion of people working in lower-paid and therefore vulnerable jobs. We have 20% less managerial, administrative or professional households than the national average. Torbay’s endangered jobs list of the near future includes fast food workers, cashiers, other shop workers, accountants, chefs and waiters.

GRADE TORBAY ENGLAND

AB 14.84% 22.96%

C1 29.85% 30.92%

C2 24.50% 20.64%

DE 30.82% 25.49%

Many jobs will remain, however. Those that involve social interaction won’t be easy for a machine to do. Social tasks – negotiating or taking care of others – may be relatively safe. These include careers such as teaching, social care and nursing. Around 6,000 people are employed in health and social care in Torbay and many of those jobs will remain – though they may further change. For example, the diagnostic role of doctors can already be done by machines, but the patient-interaction aspect of the job is hard to replace. Working alongside machines to give them a human interface is also an opening – in the Newton Road ASDA there’s a lovely lady who rescues those of us not used to the self-service tills. She uses her human skills, but note that she has effectively replaced six other human staff.

Many jobs will remain, however. Those that involve social interaction won’t be easy for a machine to do. Social tasks – negotiating or taking care of others – may be relatively safe. These include careers such as teaching, social care and nursing. Around 6,000 people are employed in health and social care in Torbay and many of those jobs will remain – though they may further change. For example, the diagnostic role of doctors can already be done by machines, but the patient-interaction aspect of the job is hard to replace. Working alongside machines to give them a human interface is also an opening – in the Newton Road ASDA there’s a lovely lady who rescues those of us not used to the self-service tills. She uses her human skills, but note that she has effectively replaced six other human staff.

Machines generally aren’t creative. They’re very good at processing problems once the issue has been identified, but they’re not as good at generating new creative ideas. So artists, writers and musicians should all be safe, along with many jobs working at high levels in the science, technology and engineering sectors.

Computer systems also are poor at making decisions for themselves. We can programme and instruct a robot to pick up bricks, for example, but a general purpose machine probably couldn’t easily differentiate between all the different objects lying around, pick them up and put them in different places.

Also, just because something can be automated, that doesn’t mean it will be. The Abbey Sand’s restaurants may install tablets on tables to take orders, and use robots to deliver your lasagne, but you may prefer to be served by a smiling waiter – and be willing to pay extra for that interaction. On the other hand, you don’t have to tip a Terminator!

Also, just because something can be automated, that doesn’t mean it will be. The Abbey Sand’s restaurants may install tablets on tables to take orders, and use robots to deliver your lasagne, but you may prefer to be served by a smiling waiter – and be willing to pay extra for that interaction. On the other hand, you don’t have to tip a Terminator!

On a larger scale, we need to ask, if not many people have a good disposable income, who is left to buy all those things that the machines are producing greater amounts of? If we are seeing the breakdown of our old income-distribution system across the industrialised world right now, we can’t just assume that the economy will naturally self-correct. The creative destruction of jobs needs to be paired with adequate provision for those who are being displaced. Post-school education is one way to help guarantee a more flexible, technologically-adept workforce. Meanwhile, the idea of a Universal Basic Income could redistribute the benefits of technological progress and provide an income during periods of unemployment and low income.

All the above, of course, may not happen. We’ve been very wrong before. Back in the 1930s the economist John Maynard Keynes said that there would be mass unemployment following the automation of mining and manufacturing. Yet Keynes, brilliant though he was, failed to predict the rise of the service economy – which now provides most of our jobs. Accordingly, even now, all our economists and thinkers may be missing something obvious. However, it’s still worth discussing Brixham, Paignton and Torquay’s future now… before we’re living it. Whether you’re a pessimist or an optimist, let’s finish with the satire of ‘the future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades’:

All the above, of course, may not happen. We’ve been very wrong before. Back in the 1930s the economist John Maynard Keynes said that there would be mass unemployment following the automation of mining and manufacturing. Yet Keynes, brilliant though he was, failed to predict the rise of the service economy – which now provides most of our jobs. Accordingly, even now, all our economists and thinkers may be missing something obvious. However, it’s still worth discussing Brixham, Paignton and Torquay’s future now… before we’re living it. Whether you’re a pessimist or an optimist, let’s finish with the satire of ‘the future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades’:

…