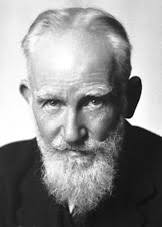

The Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) wrote more than 60 plays and is the only person to have been awarded both a Nobel Prize for Literature (1925) and an Oscar (1938) – for ‘Pygmalion’.

He was also a regular summer visitor to the Hydropathic Hotel above Meadfoot Beach. He appreciated what Torquay had to offer, “No housekeeping, plenty of bathing, taxicabs to get around in, shops galore, and every sort of urban amenity.” He also records visiting the striking Vane Tower (below).

He used his knowledge of Torquay to base one of his plays in the Bay. This was ‘You Never Can Tell’, written in 1897, which became the BBC Play of the Month in 1977, featuring Cyril Cusack, Patrick Magee, Judy Parfitt and Robert Powell. It was described at the time: “Shaw’s comic tour-de-force is set beside the seaside where a holiday atmosphere prevails. Amidst the sunshine and sea air, against a background of a fancy dress party and luncheon, Shaw uses his lightest touch to explore the battle of the sexes, the absurdities of marriage and the generation gap.”

“The enlightened Mrs. Lanfrey Clandon and her three clever and unconventional children have returned to England after eighteen years of living abroad. Whilst staying at a Hotel in Torbay the family bumps into the staunchly traditional father they had previously abandoned. Add into the equation an impoverished dentist, an eminent QC and a seemingly all-knowing waiter.”

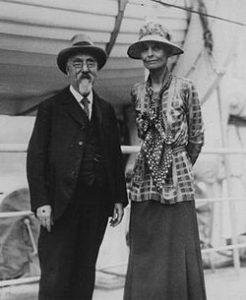

Always political and concerned with social issues, the outbreak of war in 1914 changed Shaw’s life. And it was during his time at the Hydro in 1914 that he wrote a series of letters to his fellow Fabians Sidney and Beatrice Webb (pictured above). These letters discussed hostilities with Germany and related the arrest of the German novelist Hedwig Sonntag, who was working as a hotel porter at the Hydro. “I got a pathetic letter this morning from Hedwig Sonntag, thanking me in moving terms for being the only honest man in England. Later in the day, he, though registered, was handcuffed and deported to the innermost centre of Britain – to Exeter, in fact. And in the evening the Coastguard threatened to shoot me and Barker on our walk before going to bed, if we approached him (we were 50 yards off).”

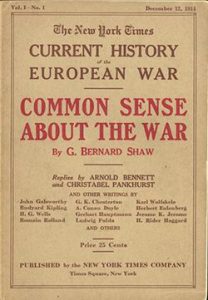

For Shaw the War represented the bankruptcy of the capitalist system and the death throes of European empires. He saw patriotism as the cause of a tragic waste of young lives. While in Torquay, he expressed his opinions in a series of newspaper articles under the title ‘Common Sense About the War‘. The essays appeared as a Special War Supplement to the New Statesman in November 14, 1914 and ‘Common Sense’ was reproduced in newspapers, such as the New York Times. Shaw later gave a copy to a friend. It was inscribed “written on the roof of the Hydro at Torquay”.

In the articles he recognised that winning was a practical necessity, but he refused to glorify the conflict in any way. He held that war could have been avoided, but was the product of a bankrupt political system, a system that required total change. Provocatively, he suggested that the troops of both armies should shoot their officers and go home. They could then, “gather in their harvests in the villages and make a revolution in the towns; and though this is not at present a practicable solution, it must be frankly mentioned, because it – or something like it – is always a possibility in a defeated conscript army if its commanders push it beyond human endurance when its eyes are opening to the fact that in murdering its neighbours it is biting off its nose to vex its face.”

Few public figures had dared to speak out in opposition to the War and the response to Shaw’s comments was predictable and vitriolic. In one response, Harold Owen wrote ‘Common Sense about the Shaw … Being a Candid Criticism of Common Sense about the War by Bernard Shaw.’ Owen wrote, “Now tell us all about the Shaw, And what he wrote his sloshtosh for.”

Consequently, during the war years Shaw’s dramatic output largely ceased. He only wrote one major play, ‘Heartbreak House’, which indicated his despair about British politics and society. The writing of ‘Common Sense’ cost Shaw greatly at the box-office. Many of his friends turned against him – he became one of the most despised men in England, and it was proposed that he should be tried for treason.