“Not always am I permitted to visit earth in my earthly form”,

the talkative St Michael’s Chapel Ghost

Now we can easily see St Michael’s Chapel there seems to have been an increase in interest in this enigmatic medieval building – particularly in the Chapel’s Ghost.

The chapel is to be found along the side of the Newton Road, right at the summit of the sheer limestone tor of Chapel Hill – as you drive out of Torquay towards Newton Abbot it’s in the woods opposite Torre Station. If you want to visit from the Newton Road, drive up Old Woods Hill, turn right at the roundabout and there’s some free parking outside Torre Primary School. A narrow path saves climbing much of the hill, but do watch where you step – the ghost is harmless but this is dog walking country!

We’ve already described a bit of the history of the chapel which is probably 13th or 14th century so won’t go over too much old ground – incidentally, the other ruins next to the chapel are much later and from the 1880s meteorological Observatory.

We’ll get to the Chapel ghost soon, but there are other mysteries connected to the site. We don’t know what it was originally called, who built it, and why someone went to the effort and expense in the first place.

First of all, there’s debate over whether the chapel should even be called St Michael’s. St Michael is a saint of high places, and there are several other St Michaels built on steep hills such as Brent Tor and in Cornwall and the one in Normandy (pictured). Yet, in 1616 John Speed called it St Marie’s Chapel as did an artist in an old map in 1662 (pictured below). One proposition is that Roger de Cockington built and dedicated the chapel to his wife Maria.

One intriguing suggestion is that the chapel was built on an older place of pre-Christian significance. It was common to build churches on former pagan sites. The Pope, Gregory I (540-604AD) instructed, “Concerning the matter of the English, the shrines of idols amongst that people should be destroyed as little as possible, but that the idols themselves that are inside them should be destroyed. Let blessed water be made and sprinkled in these shrines, let altars be constructed and relics placed there… that they should be converted from the worship of demons to the service of the true God, so that as long as that people do not see their very shrines being destroyed they may put out error from their hearts and in knowledge and adoration of the true God they may gather at their accustomed places more readily.”

It’s worth noting that the Archangel Michael was the field commander of the Army of God in the Books of Daniel, Jude and Revelation. Michael led God’s armies against Satan’s forces during his uprising, and so, it’s been proposed, that Torre’s early Christians acquired the site for their new religion and named it to establish a victory over evil, with the present chapel coming later.

While most historians assume that the chapel belonged to Torre Abbey, it’s a bit strange that Episcopal registers and cartularies don’t record its existence. Oddly, no attempt has been made to cut away or level the rock floor inside the building to make it usable for a presumed congregation. Consequently, a variety of suggestions have been made to why it was built in the first place. It has been described as a sea mark, the abode of a hermit, a place of retreat, of punishment, or a votive chapel built by mariners who had escaped ship wreck.

In place of good historical evidence, we have a folk tale which inevitably involves a ghost and a beautiful maiden. The story is related in the 1850 book ‘Legends of Torquay’ and is repeated in Arthur Charles Ellis’ ‘Historical Survey of Torquay’ in 1930.

Here’s an abridged version.

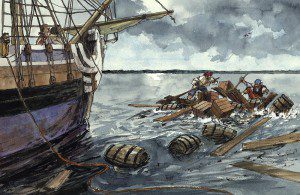

One night a terrible storm raged while the white-robed canons of Torre Abbey were praying – that’s one pictured on the right. Suddenly a man rushes in to announce that a vessel was drifting on to Abbey Sands. The canons went to the beach to find a huge ship illuminated by lightning flashes. Though beacons were lit, the ship sank with all the crew being tragically lost except for one man who was carried to the Abbey and nursed back to full health. In thanks for his life being saved he decides to devote his remaining days to the service of God. He then built a little chapel on the hill where he could see the spot where his ship went down. There he lived the rest of his life as a hermit and could be heard praying for the safety of those at sea whenever storms raged in the Bay.

That the chapel should have becomes associated with seafarers isn’t unusual as there is a strong link between ecclesiastical communities and the sea. Medieval monks and hermits did help shipwrecked sailors, build chapels to guide seafarers, and, indeed, to profit from salvaged goods. Chapel Hill, however, is a long way inland, and the cliffs at Rock Walk may have been more visible to navigators. Nevertheless, the chapel was certainly significant for mariners – a guidebook of 1793 reports that, “The Tor Chapel, perched on the summit of the ridge of rocks, once an appendage of the abbey before us and as it has not been desecrated it is sometimes visited by Roman Catholic crews of the ships lying in the bay.”

To continue the story, three hundred years after the hermit’s term of residence a youth arrives at the chapel seeking knowledge. He is, however, dismissive of the story of the hermit’s dedication. While contemplating his place in the universe he falls asleep and dreams that he finds his way inside the chapel, finding it brilliantly illuminated by two lamps in the recess of the northern wall. He is joined by an old man with long white hair who reproaches him for his scepticism. The elderly hermit – for it is he – prophesies that one day the young man will be grateful to the builder of the chapel. Our hero then awakens.

Time passes and he falls in love with a maid by the name of Rosalind. Our Torquay couple often discuss the strange dream as they sat on the grass outside the chapel. It may be significant that the name of Rosalind would be familiar to most people in the early modern period. Rosalind is the beautiful protagonist of Shakespeare’s play ‘As You like It’ (1600) and exemplifies the best of the virtues to be found in a Renaissance English woman. Youthful, intelligent and witty she is the faithful lover of Orlando and a similar loyal personality to the Torquay Rosalind who we will come to know as the tale progresses.

Yet, soon the romantic couple had to part as our hero needed to travel across the sea, not expecting to return for three years. Rosalind promises to visit the chapel on every anniversary of his departure and does so though, after 3 years, her lover still hadn’t returned. On the final anniversary Rosalind journeys through another terrible Torquay storm to the Chapel, reaching the summit of the hill late at night. She is surprised to see a light burning and, on entering the porch, sees an old man who she recognises from her lover’s description. The hermit tells her that her true love is in an imperilled ship in the Bay battling the elements. For a bit of added melodrama he concludes with, “Since these strong walls were raised no storm has swept along this coast like that which comes tonight”.

Together they leave the chapel and make their way to the beach to find an apparently lifeless body rolling over and over in the shallow waters. Dragging the man to safety they then take him to the nearest habitation. As often happens in these tales Rosalind promptly faints. On waking she is greeted by her recovered long-lost love.

Though the storm has ended the old man has lingered on and delivers a lengthy address – presumably after 300 years of being alone he has been preparing a speech, “Tell him, my child, that even he who scoffed at it erewhile, has cause for thankfulness for my pious work. Not always am I permitted to visit earth, in my earthly form, but for some good end or wise design. But, maiden, hear my latest words. When any shall seek the grey chapel yonder, with reverence and worship in their hearts, to muse on good times gone by, the spirit such meditations invoke shall leave within each breast some lasting good. When any shall seek it in sorrow and distress the same spirit shall soothe and comfort their hearts. When any shall come to bewail some bygone sin and drop the penitential tear upon the rugged floor, not idle will that spirit be to teach their hearts aright and lead to hope and life. Farewell. Remember me.”

Fortunately, someone had the foresight to write all this down. The verbose hermit then disappears but – our informants tell us – the story has been handed down through the ages, to finally end up here on WASD!