Here at WASD we recently ran an article about Torquay’s site for public executions, Gallows Gate. There seems to have been some interest in our town’s place of terminal justice and questions have come in asking what actually took place up on the hill. As a bit of a warning, what follows may not be to everyone’s taste, so stop reading now if you find this part of our local heritage distasteful.

First of all its location. Gallows Gate is just by the roundabout at the top of Hamelin Way on the A380. At around 495 feet above sea level, the site is on an ancient ridge way and where the four parishes of Cockington, Marldon, Kingskerswell and St Marychurch meet.

It looks like the gallows was in use for a very long time. The Haytor Hundred is recorded as being held at Kingsland – the King’s Land. This would have seen gatherings of men called to fight and hold open air courts, as well as providing a good lookout for sighting hostile ships in the Bay. The partition of Devon into Hundreds dates from King Alfred (871-901) and so this could mean that Gallows Gate served for well over a thousand years as a place of execution. Even if only a couple of people a year were executed here, over its long history many hundreds would have lost their lives in this unnoticed plot of land by the side of one of the Bay’s busiest roads.

Death by hanging was always the main form of execution in England. It was introduced to Britain by Anglo-Saxon tribes as early as the fifth century, gallows being an important part of Germanic culture. Though William the Conqueror decreed that hanging should be replaced by castration and blinding for all but the crime of poaching royal deer, hanging was reintroduced by Henry I as the means of execution for a large number of offenses.

Yet, hanging wasn’t the only form of judicial killing during the medieval period being used to punish crime and to suppress religious or political dissent. Different types of capital punishment depended on the crime and the social status of the victim: in 1401 burning was made the penalty for heresy, symbolising the flames that awaited in hell; women found guilty of counterfeiting or murdering their husbands were also burned – burning as a punishment was abolished in 1790; beheading was normally reserved for the highborn and was last used in 1747; boiling was reserved for poisoners; in 1563 Elizabeth’s government passed a law making it a capital offence to cause the death of a person by witchcraft – in England witches being hanged not burned.

The most extreme form of punishment was to be Hung, Drawn and Quartered. This was reserved for the most loathed prisoners who had usually been convicted of treason. The Quarters of the body were then hung in prescribed locations as a deterrent to all. Indeed, Gallows Gate may have seen the remains of the martyr Cuthbert Mayne who converted to Catholicism in 1570 and attempted to convert the Cornish. He was arrested for the crime of being a priest and on November 12 1577 was executed at Launceston. Instructions were given for a “quarter of his body to be put on a pole at Torquay’”. This appears to be the first mention of the name ‘Torquay’ for our town.

Yet, even though Torre Abbey was the richest Premonstratensian abbey in England we weren’t that involved in national political and religious struggles. It’s likely, therefore, that the executions carried out at Gallows Gate were predominantly by hanging. These were for local poor folk not worth more than a cheap and minimal effort dispatching at the end of a rope.

It’s worth noting how widely the death penalty was used in medieval and modern England – before the development of the prison system which offered an alternative. During the reign of Henry VIII, for example, 72,000 people are estimated to have been executed. By 1820, there were 160 crimes punishable by death, including shoplifting, petty theft, and cutting down trees. The criminal justice system did not distinguish between adults and children, and “strong evidence of malice in a child of 7 to 14 years of age” was also a hanging offence.

Alongside the death penalty a range of other physical punishments were frequently imposed. In 1436 the Cockington Manor Court referred to a ‘stope’, usually defined as a gibbet or whipping post which could be at Gallows Gate. Here criminals could be branded by a hot iron, whipped “at the cart’s tail” or publicly shamed by being set in the pillory and pelted with rotten vegetables.

We don’t have any specific records of local executions so we need to rely on narratives from other parts of the country. These tell us that the condemned person was usually placed beneath the gallows on a horse drawn cart. Once the rope was around the neck the horse was led away and the person left to hang. This method often meant the person died slowly of strangulation. While from the 18th century trapdoors came into use in major towns, this level of sophistication may not have reached rural ‘Torquay’.

A visiting Frenchman observed an eighteenth century execution: “The chaplain who accompanies the condemned men is also on the cart; he makes pray and sings a few verses of the Psalms. Relatives are permitted to mount the cart and take farewell. The executioner covers the eyes and faces of the prisoners with their caps and lashes the horses that draw the cart, which slips from under the condemned men’s feet. You often see friends and relations tugging at the hanging men’s feet so that they should die quicker and not suffer.”

These were very public executions designed to act as a deterrent – “Executions are intended to draw spectators. If they don’t draw spectators, they don’t answer their purpose”, wrote Samuel Johnson (1709-1784). They showed the power of justice. The French word for gallows, ‘potence’, comes from the Latin word potentia, meaning ‘power’. Accordingly, gallows were often sited in open spaces to accommodate large crowds. They were located at the edges of towns, by roads, or on hilltops where victims could be seen – hence, the high ground before travellers descended to the small communities of our Bay.

For centuries hangings were one of the most popular forms of entertainment in England, attracting crowds and generating a carnival atmosphere. People of all ages jostled to obtain the best view, their mood varying according to their sympathies with the criminal and one could see “ragged children darting to and fro to play their usual pranks at the foot of the gallows.” Hangings could see white doves released by spectators to express their sorrow, while some viewed criminals as heroic figures – highwaymen in particular were held in high esteem by many people and celebrated in popular culture.

The last public hanging in England took place in 1868. The Times covered the event in some detail and noted, “The vast concourse of spectators. There were the usual cat-calls, comic choruses, dances, and even mock hymns. Some laughed, some fought, some preached, some gave tracts, and some sang hymns. It was a wild, rough crowd, with hordes of thieves and prostitutes.”

The idea of an execution as entertainment didn’t die easily. As late as 1865 Torquay’s entrepreneurs organised a day out to attend the hanging of the Lowe’s Bridge baby-killer Charlotte Winsor in Exeter, with a visit on the way home to Newton Abbot Races thrown in – Winsor, however, escaped execution on a legal technicality.

We are often unsure of the exact location of a gallows and have to rely on place names. Gallows Gate is fairly straightforward. Another name that indicates such a location could be ‘Forches’, deriving from the Latin ‘furcus’, an old term for gallows. This would indicate that Forches Cross near Newton Abbot was another edge-of-town location. One reason for our difficulty is due to the way that the bodies were disposed of, so little remaining in the archaeological record. The bodies and clothes of the dead belonged to the executioner – relatives had to buy them from him. At other times, after the corpses were cut down from the gallows, there was a rush to grab the bodies, as some believed their hair and body parts were effective in healing diseases.

To the south of Gallows Gate is Dada Croft. The similar sounding ‘daudaz’ is Saxon for ‘dead’, so it’s reasonable to see this small enclosed field as a place reserved for the remains of those who died in the immediate area. As murderers and suicides were denied Christian burial, these unconsecrated burial grounds near execution sites were prime candidates for ghosts and were avoided at night. To prevent any rising of the dead, bodies were often dismembered and buried with a wooden stake driven through the remains and left sticking out of the ground as a warning. An Act of Parliament finally prohibited staking in 1823.

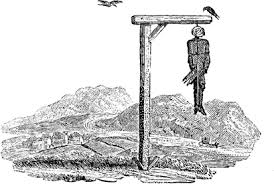

Another reason why gallows were sited away from human habitation is the use of a gibbet. Gallows Gate had such a gibbet, where executed criminals could be left to rot. Up to the late seventeenth century, live gibbeting also took place, in which the criminal was placed in a metal cage and left to die of thirst. Such gibbeting became common in the mid-eighteenth century due to a perceived increase in murders, and was regularised in England by the Murder Act of 1752. This stipulated that “in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried”, the cadaver was either to be publicly dissected or left “hanging in chains”. This was a time when Christians believed in bodily resurrection so the idea that after their death their body would be cut up or eaten by carrion crows was horrifying and added an extra punishment. The practice ended in 1832 but it took a few decades before the last gibbet was removed.

Our visiting Frenchman observed, “After hanging murderers are punished in a particular fashion. They are first hung on the common gibbet, their bodies are then covered with tallow and fat substances, over this is placed a tarred shirt fastened down with iron bands, and the bodies are hung with chains to the gibbet and there it hangs till it falls to dust. This is what is called in this country to hang in chains.”

Yet by the end of the eighteenth century attitudes were changing. In 1770 the politician William Meredith, suggested “more proportionate punishments” and bills were being introduced into Parliament in an attempt to de-capitalise minor crimes. This may explain why Torquay’s gallows was moved 170 meters south to its present position. Originally it appears to have been at Kingsland, the highest point and where the reservoir now is. One suggestion is that the gallows were relocated in the 1820s when public opinion began to turn against disorderly public hangings and the suspended rotting corpses which could be seen for miles around. It was also becoming recognised that many crimes were committed by people in poverty and the sheer number of people hanged for petty crimes was causing unrest. As the nineteenth century progressed it was clear that public spectacles did not deter desperate people but they did encourage political agitation and allowed thieves easy pickings in the watching crowds.

After 1861 capital punishment was only retained for the four crimes of murder, piracy, arson in the Royal Dockyards, and high treason. It wasn’t until the Prisons Act of 1868 that executions had to take place hidden inside prison walls. The Bay’s offenders then ended their lives at Exeter Prison where hangings took place in a purpose-built execution shed. Yet, even with the more professional ‘long-drop’, mistakes were still made – notably in the failed attempts to execute John ‘Babbacombe’ Lee in February 1885.

In Britain the death penalty was abandoned for an experimental period in 1965 and abolished permanently in 1969. Free votes were held on the restoration of capital punishment in 1979 and 1994 but both times it was rejected. Even after this the death penalty theoretically survived for treason, piracy with violence, arson in a royal dockyard and certain crimes under the jurisdiction of the armed forces. Finally, the ratification of the 6th protocol of the European Convention on Human Rights on 20 May 1999 abolished the death penalty in the United Kingdom.

The death penalty, on the other hand, remains in 77 countries across the world.

Here’s Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant & Jimmy Page with their version of the centuries-old folk song ‘Gallows Pole’ at the Paris Concert for Amnesty International in 1998:

…