During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries some British towns and cities with large factories had set periods when the workforce would all take their holidays at the same time. These were ‘wakes weeks’ which were originally religious celebrations which developed into secular holidays during the industrial revolution. For example, in Scotland each city had a ‘trades fortnight’ – two weeks in the summer when tradesmen took their holidays.

The observance of the wakes week holidays has now largely now disappeared due to the decline of manufacturing industries and the standardisation of school holidays.

Nevertheless, at the time these wakes weeks had a significant effect on people’s behaviour. People on holiday, for example, were less likely to buy a newspaper. This could really impact on a paper’s sales as circulation could drop sharply in those summer weeks. In response, newspaper proprietors would offer prizes to attract buyers. One such early competition that ran for over a century began the British summer tradition of hunting the ‘mystery man’.

This involved readers having to track down and identify the newspaper’s ‘mystery man’ who could be found in a particular area of a town or city. If successful, they were rewarded with a cash sum. As many of the newspaper’s absent readers were on the beach, the mystery men were sent off to holiday resorts such as Torquay during the holiday periods.

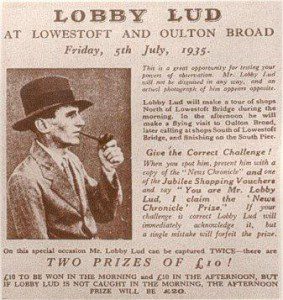

The first was the character of Lobby Lud, invented in August 1927 by the Westminster Gazette, now long extinct. The name came from the paper’s telegraphic address of ‘Lobby, Ludgate’. The paper would announce that Lobby Lud would be wandering in a particular location and publish his photograph and description. Readers would the rush off to try and find him. The reader had to have a copy of the newspaper and challenge him with the words “You are Mr. Lobby Lud. I claim the Westminster Gazette prize”.

The prize was £5 – about £300 in 2018’s money. If Lobby Lud couldn’t be identified on a particular day, the reward would accumulate to a maximum amount, making it well worth winning. The original Lobby Lud was William Chinn, one of the Westminster Gazette’s reporters- in 1983 William was discovered aged 91 in Cardiff.

After the demise of the Gazette in 1928 the competition continued in the Daily News from 1930, which then became the Daily Mail in 1960.

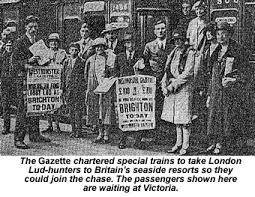

The hunt for Lobby became a popular event – there was even a train, the Lobby Lud Express, which was run to take Londoners to the resorts Lobby visited. As the competitions brought in an influx of Lud-hunters and extra income for the town, Torquay’s councillors welcomed the visit of Lobby.

The character became so well known that he turned up in movies and books. Graham Greene’s ‘Brighton Rock’ (1938) uses a Lobby Lud character called Killey Kibber, and Agatha Christie’s 1924 story ‘The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan’ has Poirot mistaken for the man in the newspaper contest, Lucky Len, while he’s on holiday at the seaside.

The phrase “You are….. and I claim my five pounds” moved into everyday use. It became a way of pointing out a similarity between two people. For instance, it was used by Private Eye – on the cover of the November 1968 issue Jackie Kennedy as a bride was captioned saying, “You are Aristotle Onassis and I claim my five million pounds”.

Yet, there was a bit of a downside for anyone who resembled the Lobby description. Many innocent look-a-likes were accosted and, when they denied being the mystery man, some were subjected to abuse.

Lobby wasn’t the only mystery man. Other newspapers and radio stations took up the idea and there was a Percy Pickles and the Guineas Man. The best known, however, was the Daily Mirror’s Chalkie White who was still visiting the Bay in the 1980s. Every so often Chalky White would wander around Torquay or Paignton waiting to be recognised by Mirror readers.

So, during the summer a picture of Chalkie’s eyes appeared in the Daily Mirror and each day we would memorise the image, along with the line we had to say to claim the £50 prize. It was usually something like, “To my delight, it’s Chalkie White”. Incidentally, the name came from Andy Capp’s friend in the long-running Daily Mirror cartoon strip, and isn’t connected to the offensive Jim Davidson stereotype.

In 2005 The Guardian interviewed ‘Chalkie’. Though not identified, Chalkie at the time was a 31-year-old Bedford man whose brother stood in for him in places such as Margate, where he was too well known. He told the paper that women and children had fought over him, and holiday plans had been altered at the last minute in an attempt to catch him.

“Last time I was in Lowestoft,” he said, “a woman and her husband followed me down to Ramsgate and slept overnight in the car to make sure they were up early enough to catch me next day.”

He was often punched by people who thought they should have won the prize and was once hit over the head with a handbag by a woman who thought it was misleading of him to wear a beard.

“People think it’s a cushy job but sometimes I hate it. You get this terrible sense of paranoia. Everywhere you go, you think everyone’s looking at you.”

Chalkie accordingly had to take precautions to avoid detection: “I start by staying in a hotel two or three miles out of the resort, otherwise you get collared at breakfast by a waitress”.

In a glimpse of what the British holiday experience was really like, Chalkie revealed his method, ” You try to look exactly like the rest of the people on the beach – miserable and aggressive.”