Today Torbay is viewed as a place of peaceful seagoing recreation, and we often see our three towns as the culmination of a peaceful journey from lowly beginnings to a unique affluence and sophistication by the conclusion of Victoria’s reign.

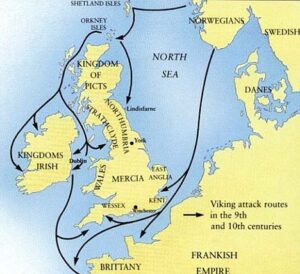

There is, however, another story. For a thousand years, hostile sails were often to be seen offshore and local folk lived in fear. From bitter experience the sea was known to carry invaders, slavers, raiders, and pirates. The attacks we most remember came from the north. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in the year 850, “Here Ealdorman Ceorl with Devonshire fought against the heathen men at Wicga’s stronghold and made a great slaughter there and took the victory.” This is all we know of that event, though we are acquainted with the ‘heathen men’. These were the Vikings who launched raids all along the coast and later inland at Exeter, Tavistock, Kingsteignton, and Lydford.

The attacks we most remember came from the north. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in the year 850, “Here Ealdorman Ceorl with Devonshire fought against the heathen men at Wicga’s stronghold and made a great slaughter there and took the victory.” This is all we know of that event, though we are acquainted with the ‘heathen men’. These were the Vikings who launched raids all along the coast and later inland at Exeter, Tavistock, Kingsteignton, and Lydford.

In 850 an Anglo-Saxon militia defeated Viking raiders near Marldon

It seems that those Vikings that landed in Devon came in small numbers. Perhaps expecting little real resistance, they were surprised by the good men of the Anglo-Saxon locally mobilised militia, the ‘fyrd’. Although the battle site has not been identified, scholars suggest that ‘Wicga’s Stronghold’, or ‘Wicanbeorg’, could be modern day Weekaborough near Marldon.

In 1978 a tenth century Viking gold arm-ring was found on the shore near Goodrington

The other evidence we have of a local Viking presence is the discovery in 1978 of a gold arm-ring on the shore near Goodrington. Dated to the tenth century, it was made in the Viking style. It is now in the British Museum and has been exhibited in Germany, Minneapolis, and New York.

The Bay had more to fear than Viking assaults. The Victorians often romanticised Anglo-Saxon England, contrasting it with the loss of freedom under the Norman yoke. Yet, this was a slave-owning society where settlements could be attacked at any time. In 1052, for instance, the future King Harold raided the coast and “seized whatever he pleased, in cattle, captives and property”.

North Africa’s Barbary Pirates raided our coast for over a hundred years

There would also be more lasting seaborne hazards. For over a hundred years, Torbay was terrorised by pirates operating from the ports of Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, an area known as the Barbary Coast. There were at one time sixty ‘Turkish men-of-war’ off our coast, seizing ships and engaging in raids, called ‘razzias’, on coastal villages. Their main purpose was to capture slaves and these Barbary pirates would anchor in the Bay to intercept fishing vessels returning from Newfoundland.

A further threat came from the Dunkirkers, raiders who operated in the English Channel during the Dutch Revolt of 1568 to 1648. In service to the Spanish monarchy, these marauders operated from the ports of Nieuwpoort, Ostend and Dunkirk and were commerce raiders, attacking merchant and fishing vessels to disrupt trade rather than getting involved in engaging other warships. Some years the Dunkirkers captured over two-hundred ships.

The Dunkirkers were commerce raiders, attacking merchant and fishing vessels to disrupt trade

South Devon’s coastal shipping was at constant risk of attack and trade almost came to a standstill. In 1630 the Mayor of Exeter warned that unless protection was forthcoming “the merchants will be undone”while Plymouth’s Mayor complained to a Parliamentary committee that, “Merchants are so disheartened they that they dare not set forth. Not a fisher boat can go from port to port, or to fish, but in danger of French or Dunkirks”. Incidentally, among the Dunkirkers hundred vessels were a type of small and manoeuvrable warship used to evade the Dutch navy. These were called frigates and still have a modern counterpart.

On occasion the Bay faced direct attack. A letter dated 19 July 1667 recounts that, “The Dutch have made an attempt at Torbay: they fired two small barques (a ship with three or more masts) at Torquay and shot at a gentleman’s house near the water but have now retreated.” It is believed that the house in question was Torre Abbey with the attack being a hit-and-run affair; a side-show in the four seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Anglo-Dutch Wars.

In February 1668 the famous diarist and MP Samuel Pepys predicted that England would soon attack France: “Everybody doth think a Warr will follow”. The provocation was a large armed French landing in Torquay. Captain Lois de la Roche in his ship the ‘Jules Cesar’ was in command of a French squadron tasked with disrupting the lines of communication between Spain and the Netherlands. The French had already captured English soldiers in Plymouth on their way to serve in Spain and was taking them to France. Two French men-of-war then spotted a Dutch vessel, the ‘St. Mary’ of Ostend, which was in Torquay harbour. The crew, “being unable to defend their ship, they bored holes into her, and escaped to shore, carrying their sails, ammunition, &c., and gave them in charge to Dan. Luscombe, of Torquay”. This included a couple of guns which were also stored with Daniel, described as “the principal man of the village”, and hidden in a private house.

Captain Lois de la Roche in his ship the ‘Jules Cesar’ was in command of a French squadron tasked with disrupting the lines of communication between Spain and the Netherlands. The French had already captured English soldiers in Plymouth on their way to serve in Spain and was taking them to France. Two French men-of-war then spotted a Dutch vessel, the ‘St. Mary’ of Ostend, which was in Torquay harbour. The crew, “being unable to defend their ship, they bored holes into her, and escaped to shore, carrying their sails, ammunition, &c., and gave them in charge to Dan. Luscombe, of Torquay”. This included a couple of guns which were also stored with Daniel, described as “the principal man of the village”, and hidden in a private house.

To acquire this prize, Captain Roche landed a force of armed men and marched them to the harbour where he acted “to seize the ammunition, stopped up the holes, and carried away the vessel.”

This was undeniably a major violation of English sovereignty and in response James II made a vigorous complaint to the French King while instructing Sir Thomas Allin to intercept Roche. The English ship ‘Monmouth’ caught up with the out-gunned French off Spithead where the prisoners and the Ostend prize were surrendered and war was averted.

Following England’s defeat at the Battle of Beachy Head in 1690, the French attacked Teignmouth

Peace was not to last, however. During the Nine Years War a French fleet used Torbay to launch a devastating attack on Teignmouth. This followed the Battle of Beachy Head, fought on 10 July 1690, where the French had their greatest naval victory over the English. The Channel then fell under French control but, instead of following up their advantage, the French headed west and anchored in the Bay. On 13 July,

“Several of their galleys drew off from the fleet and made towards a weak, unfortified place, called Teignmouth. Coming very near, and having played the cannon of their galleys upon the town, and shot near two hundred great shots therein, to drive away the poor inhabitants, they landed about seven hundred of their men, and began to fire and plunder the towns of East and West Teignmouth, which consist of about three hundred houses.”

The French ransacked the town for twelve hours and destroyed eleven ships, “killing very many cattle and pigs which they left dead in the streets”. Reinforcing the fact that this was also a religious conflict, they “entered the two churches, tore Bibles and Common Prayer Books in pieces, broke down the pulpits, and overthrew the communion tables”.

After the attack, as the French fleet weighed anchor and sailed past Berry Head, “two slaves leaped from one of the galleys into the sea – one was recaptured; the second a Turk, after a desperate struggle for liberty, swam on shore, and was secured by the people who had witnessed the incident.”

Torre Abbey’s gatehouse, discouraging attacks for hundreds of years

That the French left Torquay in peace, as did many other raiding parties, may be due to Torre Abbey’s imposing gatehouse. Though most of the Abbey’s defences had been stripped after the Dissolution in 1537, from a spyglass out at sea the derelict gatehouse could still give the impression of being a strong fortification. Indeed, for centuries Torre Abbey appears to have discouraged seaborne attacks on Torbay.

By the eighteenth century the Royal Navy had achieved control of the English Channel, though the French would continue to contest British supremacy. Nevertheless, a watchful eye always needed to be kept on the waves.

Torquay: A Social History by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Fleet Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon