Is Torre Abbey a monastery? Did it have monks or canons and is there a difference?

The earliest Saxon churches were modest wooden structures and many now lie under the stone built places of worship that replaced them in the eleventh and twelfth centuries – St Marychurch and Torre are good examples.

As the kingdom of Wessex expanded westwards, a new diocese was created at Sherborne in 705. This acted as the mother church of Somerset, Dorset and Devon. By 909 new bishoprics were established at Wells, for Somerset, and Crediton for Devon; and in 931 St Germans for Cornwall. In 1050, the dioceses were formally merged and a new ‘see’ – the bishop’s jurisdiction – established at Exeter.

There were only two monasteries in Devon at the time of Norman Conquest, Tavistock founded in 974; and Buckfast under Cnut in 1030, both Benedictine houses. It was after 1066 that we see the spread of abbeys and priories as the great continental movements of monastic reform reached England. Eventually there would be forty religious houses across the county. They used a variety of names to describe themselves over the centuries though, even at the time they were operating, some used terms interchangeably. What is important is that abbeys and monasteries were not the same type of institutions.

Eventually there would be forty religious houses across the county. They used a variety of names to describe themselves over the centuries though, even at the time they were operating, some used terms interchangeably. What is important is that abbeys and monasteries were not the same type of institutions.

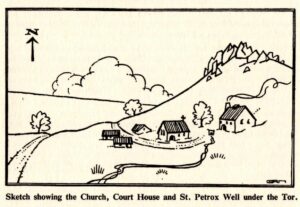

This revolution in practice came to the Bay in 1196 when six canons from Nottinghamshire’s Welbeck Abbey founded Torre Abbey. This new form of institution was made possible when William Brewer, lord of the manor of Torre, gave them the land.

The Abbey’s founders came from the Roman Catholic religious Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré. Founded in northern France in 1120 by Norbert of Xanten, the order was approved by Rome in 1126 and quickly spread over Western Europe. They were also known as the Premonstratensians, after their home town of Prémontré, and the Norbertines, after their founder; in Britain they were called the White Canons, a reference to the colour of their habits.

This is where the difference lies as their new house was an abbey and not the kind of monasteries that the English were familiar with.

The term monastery comes from the Greek ‘monazein’, meaning to live alone. Originally, monks lived in isolated huts, gathering together for meals and prayer. Gradually monks came together to live in a monastery detached from the outer world. Dedicated to their faith and religious teachings, their main duties were to pray, read the Bible and meditate on it according to the Rule of Benedict. They would engage in work that would sustain them, like gardening, Importantly, Devon’s monasteries did not have any kind of official or powerful leader, and were easy prey to marauding Vikings and other predators.

The Premonstratensians and other traditions had a different approach. Abbey comes from the Latin word, ‘abbatia’ from the word ‘father’. An abbey is a home for a religious fraternity but it isn’t just a church or a place of worship. The order combined the contemplative life of the sealed-off monks and linked it with the outward-looking approach of the friars of the thirteenth century.

Accordingly, the Premonstratensians were not inward-looking monks but canons. Canons were clerics who lived together and, like the secular clergy, had duties beyond their own buildings. Their work involved the exercising of pastoral ministry, frequently serving in parishes close to their abbey. In a life of great austerity, they engaged in acts of mercy, in preaching, and in public liturgy. They spread the faith, taught and trained young monks and priests. An abbey was a sacred place, but every abbey had a leader, called an abbot, the spiritual leader of a community; their status almost being the same as a bishop.

All abbeys are monasteries, but all monasteries are not abbeys. A monastery is the pre-stage of a building to become an abbey. Monasteries became abbeys with time as the Church bestowed the reputation on them.

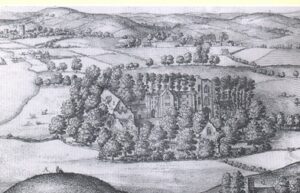

The layout of abbeys often followed a set plan determined by the founding religious order. They provided a complex of buildings for religious activities, work, and housing. They were also, particularly the gatehouse, designed to impress and dominate, and intended to be self-sufficient while using any produce or skill to provide care to the poor and needy, refuge to the persecuted, and education to the young.

Over time Torre Abbey became a very rich and powerful place; eventually acquiring an annual income that made it the wealthiest of all the Premonstratensian houses in England.

Accordingly, the Abbey attracted the attention of those with less sacred motives. This was an institution with extensive resources and potential patronage opportunities – it could dispense benefices and employment and grant leases on lands and tithes. It was big business, so who was in charge mattered. Disputes over control and profit lead to a coup, kidnap and murder in 1351, and we can assume that many other internal conflicts were resolved in similar non-spiritual ways.

The final closure of the Abbey in 1539 passed without open opposition, and immediately after a 21-year lease of the site was acquired by the Sherriff of Devon Sir Hugh Pollard. This wasn’t a violent seizure as generous pensions were awarded to the abbots. But it was the greatest change in land ownership in the Bay since the Norman Conquest. After 400 years, the Abbey faded from history.