Today Kents Cavern is a fine tourist attraction and well worth a visit. But what about the actual name of ‘Kent’?

One – admittedly fanciful – explanation is that it derives from the medieval Sir Kenneth Kent and, of course, there’s a Torquay ghost attached to the legend.

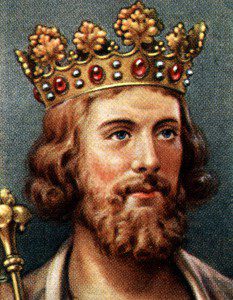

Here’s a bit of background to the Torquay story: Edward II (1284-1327) ruled England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. Between the successful reigns of his father Edward I and son Edward III, the reign of Edward II is often portrayed as disastrous for England, and it’s known for incompetence, political discord and military defeats – such as Bannockburn where we came second.

Edward (above) fathered at least five children by two women, but was rumoured to have been bisexual. Specifically, the King had a close and controversial relationship with Piers Gaveston who had joined his household in 1300. Notably, he was portrayed as an effeminate gay man in Mel Gibson’s historically deeply-unreliable movie Braveheart.

Edward died in Berkeley Castle, allegedly by murder. And it was ‘popularly rumoured’ that he had been suffocated or strangled, though most chronicles don’t offer a cause of death other than natural causes. There’s also a theory that he didn’t even die in 1327, but lived on. The popular story that the King was assassinated by having a red-hot poker thrust up him, however, has no basis in accounts recorded by Edward’s contemporaries – consequently, this may just be a bit of homophobic propaganda. That’s Edward and Piers below depicted below shortly before the alleged and deeply unpleasant red hot poker incident – note the less-than-subtle message of the image.

One of those supposedly involved in the death of Edward was Sir Kenneth Kent… and that’s where we get the Torquay connection. After the dirty deed was done, Sir Kenneth returned to the Bay to be with the woman he loved. This was Serena, the daughter of Sir Harry Lacey, a man fiercely protective of his daughter’s honour. Many legends include themes of tragedy and retribution for wrongs committed, and so we have an outraged Sir Harry plotting the death of Sir Kenneth.

In the legend, Serena warns Kent of the plans being drawn against him and he escapes to hide in Kents Cavern – hence the name. A fisherman witnessed Serena climbing to the Cavern with a lantern to join him in his escape. Neither was seen again and they were both thought to have fled to safety. Yet, many years later it was said that a brave man went to explore the caves. Deep inside the Cavern, he found a rusty suit of mail. Alongside Kenneth’s remains hovered a pale shape…

So, did Kenneth kill the King and collapse in Kent’s Cavern and lend his name to the caves?

Probably not – the earliest mention of the Cavern by name is in 1659. As with a number of other Torquay legends, it may have been invented by Victorian tourist guides looking to enhance their gratuities. Indeed, there doesn’t even seem to be a record of a Sir Kenneth Kent being involved with the Edward II story.

The name of Kent, therefore, has another origin – and there is a connection to the county of the same name. However, the nice local rhyme, indicating that the caves were so extensive that they ended in Kent, isn’t it! In this ryme we are told of a dog lost in the tunnels of the Cavern. When he emerges on the other side of the country he has lost all his fur to the grasping hands of subterranean pixies:

” ‘an’ ee he went

an’ ee went

until ee come out

in the county of Kent”.

Caves are mysterious places and attract stories and theories. Indeed, there was an early Victorian belief that the god Mithras was worshipped in the caves during the third century. What a Roman mystery religion was doing in Torbay is sadly also a mystery and doesn’t have any supporting evidence. So, if we discount the Sir Kenneth and pixie explanations, it’s more likely is that the name originates in the Celtic ‘canto’ meaning ‘border’ or ‘coastal’. Hence, in Devon we have Kenn and Kenton. The County of Kent and Canterbury have the same source.

Surprisingly not all past tourists have initially been impressed. Pictured above is the author Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) who appears to have been a miserable sod. She visited Torquay in 1893 (pictured outside the Caverns, below) and, after criticising other aspects of our town, she turned her attention to the caves:

“I can imagine no more unlikely or unromantic situation for a cavern. It is in a suburb of Torquay, half way up a tangled bluff, with villas and gardens overhanging the top of a muddy orchard with some filthily dirty cows in the ravine below… The dilapidated wooden door was flush with the bank. Outside an artificial plateau or spoil-bank of slate overgrown. A donkey-cart was encamped and the donkey grazing. The owner, a mild light-haired young man, was sawing planks. Papa enquired if there was anyone here, to which he replied with asperity ‘I am’, put on his coat and prepared to unlock the cavern. The youth hung a notice board outside the door saying that the Guide was in the cave and scrubbed out certain derisive remarks which had been scratched on the portal since the last descent.

“I implored him to take a good supply of matches. There was a quantity of ginger beer in a nice cool place, also an umbrella stand. I shall not go into details about the cave, which is well described in a pamphlet, and only remark it is very easy to explore and only moderately damp. Papa got dirty enough in all conscience, slipping off a board into the sticky red clay. I was puzzled by one feature which I took to be geological, but was in fact the dripping of innumerable candles”

Remarkably, Beatrix, who seemed to spend much of her time slagging off the places she visited, finally found herself ever so slightly impressed: “I who had never been in a cave was extremely interested.”

To end we have the experiences of the Canadian traveller Isabella Cowen. From November 1892 to March 1893 Isabella visited Torquay and her ‘Aunt Belle’s Diaries’ tell of her experience of Kents Cavern. Though they had a guide, they couldn’t see much by the three candles provided. They were also a little put out as, “the guide would not allow us to break off any specimens with my hammer”. Not all was lost, however, as, “If I would let him take it he would give us each a piece which he would break off a fallen stalactite.” It’s probably worth pointing out that you’re not allowed to do that any more…