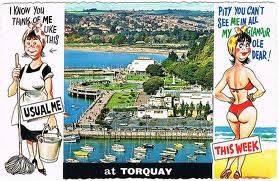

Seaside rock is a British phenomenon. Wherever there’s a British working class tourist, there’s rock – from Blackpool, Benidorm, and, of course, Torquay.

The Americans have a barber’s pole-style candy cane, which are often used as Christmas decorations, though they never have got around to inserting letters through it. The ancestor of the stick of rock is the strips of raw sugar cane given to children to suck. Sugar was expensive when it first came to Britain, but by the nineteenth century supply increased and the price came down. Sweets with lettering were apparently already being sold by 1800 and rock, as a form of sweet, was first offered at fairgrounds in the nineteenth century and known as Fair Rock.

Its association with the seaside is linked to either Ben Bullock or a man known as Dynamite Dick. Ben Bullock began manufacturing sticks of coloured lettered sweets at his Yorkshire-based confectionary factory in 1887 – he thought of the idea while on holiday in Blackpool. Alternatively, Dynamite Dick (who came from either Morecombe or Blackpool) is said to have borrowed the idea of Fair Rock and added lettering.

The seaside rock trade is a traditional cottage industry. The art of putting the lettering into the rock is a skill mastered only by the Sugar Boiler, which could take many years of experience with practices passed down from father to son. Consequently, Sugar Boilers were hard to come by and difficult to discipline. Indeed, their independence is the origin of an urban myth: the rebellious Sugar Boiler inserting abusive messages into a stick of rock.

This one has, however, some basis in an actual Torquay incident.

In February 1977 the Guardian ran a story about a dissatisfied sugar boiler at a Torquay seaside rock factory. Michael Leigh, chief sugar boiler and lettering artist to Torquay rock maker Graham da Costa, inserted the word ‘BALLS’ into more than 1,000 sticks of rock, betraying his feelings about things in general and, on that day, rock-making in particular.

Mr. Leigh said, “Well, you know how it is sometimes. We’ve just opened up for the year. We have to work up to about 16 boilings a day. You get new staff and some who are brighter than others. Then a few boilings go wrong. Then the boss says he’s coming in to help, and he doesn’t come in.”

He went on to reveal that the word he originally wanted to insert was ‘BOLLOCKS’ – predating the Sex Pistols use in the title of their album by seven months. It seems that Mr. da Costa was well aware that Sugar Boilers were temperamental artists and not easily replaced, so nothing came of the incident – except a great deal of free publicity for the Torquay rock maker. The rock itself was subsequently given away.

In Torquay, rock hasn’t always fitted in with the town’s self-image. It was associated with the working class and may even symbolise Torquay’s move away from being a health spa for the elite to a tourist resort for the masses. With the advent of the railways, people came down from the collieries, steelworks and factories. They just wanted to have fun, and a cheap and cheerful gift to bring home as a souvenir.

Rock is, therefore, the antithesis of sophistication. As can be seen on Torquay harbour side, it can be formed into different shapes – from the replicas of the ‘Full English Breakfast’ and babies’ dummies to ‘big knockers’ and willies on a stick.

The naughtiness, indiscipline and rowdiness of the seaside, more familiar in Blackpool and Skegness, was frowned upon by Torquay’s elite. Nevertheless, the association of rock with crude humour has a long history and was immortalized by George Formby (1904-1961). George performed at the Pavilion in 1955 so let’s hope he substituted Torquay for Blackpool!

Here’s George with his 1937 song, ‘With my little stick of Blackpool Rock’, which was banned by the BBC due to its suggestive lyrics: