Just next to Torquay Police Station in Torre is an unusual four-storey building.

This is the old Torre Conservative Club and it has an important place in Torquay’s history.

It was originally a Constitutional Club. These were founded in the 1880s in anticipation of the electoral reform that was being debated in Parliament. Eventually major democratic change came in through the 1884 Representation of the People Act. This gave men paying an annual rental of £10, and those holding land valued at £10, the franchise. The Act didn’t establish universal suffrage, however, as all women and 40% of adult males were still unable to vote.

The Act did increase the British electorate to over 5,500,000 and it was anticipated that many more Conservative supporters would take the opportunity to vote and that they would also want to belong to a Conservative club. Hence, the Constitutional Clubs which were closely aligned to the Conservative party, with members having to pledge support.

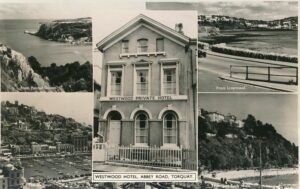

The original Torquay Constitutional Club had been founded by William Henry Kitson in ‘Westwood’ in Abbey Road in around 1883. It was already very popular and so a larger premises was urgently sought. In 1888 a committee was formed to acquire a suitable site and the present building was the result.

This was to be a conversion of a building that was originally constructed in 1866 in South Street and not a new build.

The planning, designing and build of the new club house was controlled and funded by members of the club itself through this specially elected committee. Like most building projects in the nineteenth century, the design was thrown open to competition and attracted a significant amount of interest from architects hoping to secure other clients and a subsequent reputation.

The successful architect in the prestigious Torre project was Mr. E Richards, while the conversion was undertaken by Mr. F Matthews of Babbacombe.

The total cost of the conversion was £5,000, but initial funds were insufficient and so 2,000 shares were then issued. Yet, while the Club was intended to be a commercial enterprise, it was made clear that the building wasn’t expected to generate large dividends. This was, primarily, a political power base. With this in mind, the location and design of the building becomes of particular interest.

If we ignore the 1960s ground-floor entrance and its current appearance, the club remains impressive on first viewing. The pointed arches, gothic detailing and the sash windows and the black-painted oriels are all original which gives an idea of its intended function.

The Constitutional Club was meant to impress, could be seen from a distance, was on a main route, and would have stood out amongst the surrounding two-storey terraces.

It was intimately linked to the commercial development of Torquay and, across the country, we see the political identity of Constitutional and Unionist Clubs influencing the design of the buildings they occupied.

Torquay’s Tory Anglicans and the self-made middle classes already favoured this Gothic style for their suburban domestic residences and carried on the tradition in the buildings they sponsored. The message this architecture conveyed followed the new Palace of Westminster (1837-67) and had associations with inherited authority, hierarchy and paternalism. But the Gothic also represented freedom, liberty, individualism and the commercial world. By the 1870s the Gothic had become synonymous with civic identity.

Yet, by the end of the 1870s Gothic architecture was becoming less popular and the Torre Club was always something of an anachronism. This may be due to the members being somewhat behind the times. On the other hand, the Gothic had the advantage of being able to easily adapt to difficult circumstances. The development of nineteenth-century Torquay was largely unplanned, resulting in many corner and irregular shaped plots. The Gothic could be made to fit, as it did in South Street.

Nevertheless, the architectural style and location did reinforce links between the local Conservative Party and the governance of the town. The club proclaimed the social and political power and influence of local Conservatism.

Recognising the importance of this new venture, the club was opened by George Henry Cadogan, 5th Earl Cadogan, Lord Privy Seal. During the event, the Chairman, Mr. JE Bovey, also thanked Torquay’s MP Mr Richard Mallock, “an inspirational and popular member”, who was responsible for the success of the Club and for spreading the Conservative message.

The club was envisioned to be only the beginning of a much larger initiative and there were ambitions to add an American Bowling Alley and an Assembly Room to hold 400 at the rear. This would be the centre of a political and social project that would guide Torquay’s development; and it was no coincidence that the club began at a time when political, social and religious challenges were emerging in a rapidly growing town.

George Henry Cadogan, 5th Earl Cadogan, Lord Privy Seal

It was intended to be a gentlemen’s club, a permanent meeting place for the exclusive use of its members. Accordingly, this was a club not open to all. It separated the male elite from the rest of the town; it was only in 1918 that women over 30 gained the vote, and in 1928 women over the age of 21. And it was during the final quarter of the nineteenth century that club life became so important for middle-class men in Torquay. Club culture offered such men the opportunity for friendship and fellowship; a respite from work but also access to Torquay’s business networks and political contacts.

Indeed, the club played an important role in the construction of middle-class masculine identity in Torquay. The class, as a social, political and economic group, was hierarchical; but the associational culture of the club bridged the differences in that class. It forged a sense of shared identity and common goals as the town evolved.

Internally, such clubs tended to have a specific look. This was a luxurious place, situated between the home and a public building and it drew on the idea of a gentleman’s house and the London club.

There were dark tones and heavy furnishings. Leather upholstery was a popular choice, not simply because of its masculine overtones, but because it was hard wearing and less likely to absorb food and tobacco smells. The Torre Club offered “commodious, Reading, Billiard and Committee rooms”. In this setting the men could articulate and negotiate their different identities. Here alliances could be made and deals agreed.

By the end of the twentieth century, the days of the social club had largely come to an end. Many of Torquay’s clubs – both social and political – had closed due to societal changes, dwindling membership numbers, and the competition from the pub chains.

By then, the role of the Clubs in projecting middle-class identity, power, authority and civic consciousness, had faded. Nevertheless, we shouldn’t forget their role in building the Torquay of today.