There have always been culture wars. These are conflicts between groups and individuals as they struggle for dominance, or to be simply heard and recognised. While mostly over beliefs, values, and practices, the contest can sometimes become violent.

Culture wars often come about in times of social and economic change and may alter the ways that people interact with each other. While they can include the traditional concerns of politics such as political parties, economics, and wealth redistribution, such conflicts go much deeper, into disagreements about history, identity, symbols, images, values and behaviour.

The 1960s was a time of such change. For many the decade began as bleak and restricted but by its close some had indisputably gained more liberty, individuality, and could look forward to a better future. Conversely, others saw a decline in morality and standards, and even an erosion of all that civilisation and faith had achieved.

Torquay experienced both the changes brought by the 1960s cultural revolution and saw resistance to it.

An increase in disposable income allowed people to spend more on leisure activities. But even though the actual peak of domestic holidays taken in Britain was in 1974, the traditional resorts had already begun to face growing competition from other destinations and activities newly accessible by increased car ownership. To fill any widening gaps in trade, something needed to be done and new opportunities were sought by both business-owners and the authorities.

For some these measures were to be found in the time-honoured replication of the success of the more-sophisticated Mediterranean resorts. What the continental Rivieras were doing, so could Torquay. But this revived the old argument, to remain upmarket, or to cater for the spending power of the masses.

For some these measures were to be found in the time-honoured replication of the success of the more-sophisticated Mediterranean resorts. What the continental Rivieras were doing, so could Torquay. But this revived the old argument, to remain upmarket, or to cater for the spending power of the masses.

The lessening prospects of the tourism-focussed business owner was just the local component in a nationwide erosion of the status and influence of the middle-class opinion-former. The 1963 Profumo Affair, that mix of sex, spies and government, had already altered the relationship between government and citizen. Traditional deference was now being replaced by suspicion and mistrust. No longer could the councillor, the bank manager, the employer, the doctor, the vicar, or the teacher, expect unquestioning deference in this new society,

It was in the late 1960s that we see the term ‘permissive society’ being used pejoratively by local cultural conservatives to criticise what they saw as a breakdown in traditional values and good behaviour. The specific offences were street violence, atheism, drug and alcohol abuse, premarital sex, divorce, and acceptance of non-traditional relationships; specifically, feminism and gay rights which were, across the nation and now in the Bay, challenging definitions of a ‘natural order’.

It was in the late 1960s that we see the term ‘permissive society’ being used pejoratively by local cultural conservatives to criticise what they saw as a breakdown in traditional values and good behaviour. The specific offences were street violence, atheism, drug and alcohol abuse, premarital sex, divorce, and acceptance of non-traditional relationships; specifically, feminism and gay rights which were, across the nation and now in the Bay, challenging definitions of a ‘natural order’.

More jobs were becoming available to women allowing them to move away from home and become more independent. 1970 brought the Equal Pay Act and women became increasingly involved in politics. The contraceptive pill was legalised for all in 1967 and gave the opportunity to broaden experiences beyond motherhood and marriage.

More jobs were becoming available to women allowing them to move away from home and become more independent. 1970 brought the Equal Pay Act and women became increasingly involved in politics. The contraceptive pill was legalised for all in 1967 and gave the opportunity to broaden experiences beyond motherhood and marriage.

All around, old certainties around class, gender and sexuality were being undermined.

Torquay had always been amongst the first provincial towns to import new ideas from the capital. Indeed, we prided ourselves on being a ‘Little London.’ But now we were seeing a transforming permissiveness, the resort becoming increasingly cosmopolitan. By the 1970s the tourism industry was changing, but it was easier to blame unconventional locals and incomers as agents of degeneration rather than longer-term shifts in consumer demand and taste.

Torquay had always been amongst the first provincial towns to import new ideas from the capital. Indeed, we prided ourselves on being a ‘Little London.’ But now we were seeing a transforming permissiveness, the resort becoming increasingly cosmopolitan. By the 1970s the tourism industry was changing, but it was easier to blame unconventional locals and incomers as agents of degeneration rather than longer-term shifts in consumer demand and taste.

Somewhat looser standards may have always been acceptable in Paignton but not in the bosom of the Queen of the English Riviera.

There had not been an organised backlash to all this change until the launch of the Nationwide Festival of Light, a grassroots evangelical campaigning movement formed by Christians. The festival was opposed to homosexuality, abortion and other manifestations of the nation’s falling away from God. A particular focus of their campaigns was what they saw as the media’s explicit depiction of sexual and violent themes. Its leading lights included the clean-up TV campaigner Mary Whitehouse, the journalist and author Malcolm Muggeridge, Cliff Richard, and a number of leading clergymen.

There had not been an organised backlash to all this change until the launch of the Nationwide Festival of Light, a grassroots evangelical campaigning movement formed by Christians. The festival was opposed to homosexuality, abortion and other manifestations of the nation’s falling away from God. A particular focus of their campaigns was what they saw as the media’s explicit depiction of sexual and violent themes. Its leading lights included the clean-up TV campaigner Mary Whitehouse, the journalist and author Malcolm Muggeridge, Cliff Richard, and a number of leading clergymen.

Cliff Richard and Mary Whitehouse

Promoting the Festival in Torquay was the Reverend Harold Smith. In a speech at the RAFA 1971 Annual Battle of Britain service held at Upton Church, he linked the fight against Nazism with the imperative to stem the tide of permissiveness. Quoting from a Festival of Light poster, he said that,

“Moral pollution needs a solution. Christian people know where the solution lies. Though faith has declined in these 30 years, God has not died – whatever humanists or radical theologians may say.

“We are concerned at the glorified violence, sadism, incest, and perversion invading public entertainment. Our protest is not a right-wing backlash of intolerance. It is a protest, not primarily about sex at all. It is a protest against all that degrades human dignity and destroys human relationships.”

The front-line between supposed progress and a disinclination to accept innovation was, and consistently had been, the Harbourside. This was the town’s tourism hub with theatres, pubs, clubs, and the grease and glitz of the arcades; the unceasing rise and fall of business enterprises, all chasing the tourist shilling, while in the interstices were always the lost and the lonely. Against this frenetic background, some saw Torquay sliding into decadence, with the Strand and its environs becoming the contested zone of advance and reaction to a perceived bacillus of licentiousness.

Here would be fought many skirmishes in the culture wars.

Taking one example from 1971, we have Ernie Garnham, the larger-than-life landlord of the Yacht on Victoria Parade, putting on strippers to entertain his Sunday lunch time crowd. With some relish, the Torquay Times journalist sent to review the entertainment wrote of how, “Paddy the stripper gyrated her way through the customers.”

The Yacht

In a revealing allusion to how much Torquay had changed from its genteel and sophisticated heyday, Ernie described his objectives:

“I am trying to get the pub known as a place where a bloke can come for a drink and a laugh without being in danger of getting thumped by layabouts… If you give them all the goodies at the beginning, they go home early and we don’t sell any beer which is the whole object… So the afternoon starts off with a talent spot. The microphone is passed around to anyone with a joke to tell… In the last show, just before closing time, she takes the lot off. That way everyone stays till the end.”

Provocatively, the Torquay Times ended their article by saying, “None of the customers seemed to see any difference between Sunday and any other day of the week – certainly for a town with so many churches, there were no religious qualms.”

On cue, the Reverend Peter McCrory issued a statement on behalf of the Torquay Christian Council:

“Torquay’s many churches appeared largely at a time when, for all his faults, Man did aspire to something higher than his purely animal nature when he realised that there were values of mind and spirit which could raise him to some relationship with his Creator…

Reverend Peter continued, ”If many of the world’s human population still grovel in a lower state of being than they need, then the strip joint and the brothel will continue to flourish as they have done since time immemorial on Sundays and any other day of the week… God made man a little lower than the angels in order that he may lord it over nature, not that nature should lord it over him.”

But not all culture wars would be peaceful or able to be resolved by debate and compromise. Some would last for many decades, always be divisive, and prove insoluble.

The most pronounced shift in attitudes and behaviour came amongst the young. While political beliefs had always divided local opinion, after the Second World War came the ‘Generation Gap’. This found some young people rejecting the value system of their parents’ generation in a new form of rebellion. This was manifested in lifestyle choice rather than in traditional right-left politics and unfamiliar social fractures were soon to be seen across the Bay. In September 1964, the President of Torquay Trades Union Council complained that,

The most pronounced shift in attitudes and behaviour came amongst the young. While political beliefs had always divided local opinion, after the Second World War came the ‘Generation Gap’. This found some young people rejecting the value system of their parents’ generation in a new form of rebellion. This was manifested in lifestyle choice rather than in traditional right-left politics and unfamiliar social fractures were soon to be seen across the Bay. In September 1964, the President of Torquay Trades Union Council complained that,

“I did not think that in the twentieth century we would have people who would walk about literally stinking. Bohemians and their unhygienic habit of sleeping rough on the beaches, and lounging on street corners, wearing al fresco attire and no shoes, and ganging together to block pavements to pedestrians.”

The focus of the union’s hostility were the men and women who represented a new counterculture. After being barred from sea-front pubs, they had found a welcome in the back-street Melville Inn and Belgrave Road’s The Rising Sun.

The focus of the union’s hostility were the men and women who represented a new counterculture. After being barred from sea-front pubs, they had found a welcome in the back-street Melville Inn and Belgrave Road’s The Rising Sun.

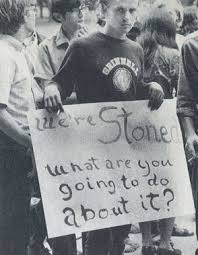

Despite the town’s long history of drug use and indulgence, the new radicalism saw a variety of substances, including semi-synthetics such as LSD, becoming negatively identified with dangerous social change. Particularly emblematic was recreational cannabis. This was a new dividing line, and the drug took became symbolic for the beatniks, their hippie successors, and the authorities. Conflict was inevitable and often centred around their use.

The Rising Sun, now DT’s

At 9.30pm on 12 April 1969, seventy members of Torbay’s Drugs Squad conducted a raid on The Rising Sun Inn. This was the first action of its kind and seventeen people were arrested, sixteen for possession under the Dangerous Drugs Act and one for wilfully obstructing Police Constable James Copeland.

In July 1969, the police warned pub landlords to be on the lookout for anyone smoking “oddly shaped cigarettes”, also telling pharmacists to be wary of customers who appeared to be “dozy, dirty, nervous, irritable or just not quite right”. Later that year they issued a statement saying they were keeping an eye on “local hippies.”

Friction between the hippies and officialdom intensified as the easy-going 1960s bled into the disenchanted subsequent decade. In early 1970 the police told the Torquay Times that the town had a drugs problem: “The drug takers are mostly young people coming down here because it is a nice place. There is plenty of accommodation and they can get casual jobs in bars, holiday camps and hotels.”

Friction between the hippies and officialdom intensified as the easy-going 1960s bled into the disenchanted subsequent decade. In early 1970 the police told the Torquay Times that the town had a drugs problem: “The drug takers are mostly young people coming down here because it is a nice place. There is plenty of accommodation and they can get casual jobs in bars, holiday camps and hotels.”

Local hippies had been complaining about the attitude of the authorities for years, believing that the town’s dependency on tourism generated a heightened intolerance of any non-standard behaviour. In March 1970, an anonymous 21-year-old hippie claimed concerted police harassment was designed to break up their community before the influx of summer visitors. He said his flat had been raided and that the police were putting pressure on landlords to turn him and his friends out of their homes:

Local hippies had been complaining about the attitude of the authorities for years, believing that the town’s dependency on tourism generated a heightened intolerance of any non-standard behaviour. In March 1970, an anonymous 21-year-old hippie claimed concerted police harassment was designed to break up their community before the influx of summer visitors. He said his flat had been raided and that the police were putting pressure on landlords to turn him and his friends out of their homes:

“They are also tightening up on the places where we meet – trying to get them to close down or to refuse to serve us. They are using the stop-and-search powers more. They’ll stop anyone who dresses differently or who has long hair.”

As the sixties ended, the mood noticeably changed. In 1972 a hundred-strong mob of men and women attacked Torquay police station, throwing bricks and bottles. The chant was “Kill the Pigs!.” Officers were assaulted, one later telling the court he thought he was going to die.

As the sixties ended, the mood noticeably changed. In 1972 a hundred-strong mob of men and women attacked Torquay police station, throwing bricks and bottles. The chant was “Kill the Pigs!.” Officers were assaulted, one later telling the court he thought he was going to die.

Yet deep-seated change can only be resisted for so long. Nevertheless, Torquay’s defenders of the greater good were still striving to hold back the tide of perceived corrupting influences even as the 1980s approached.

In 1979 ‘Monty Python’s Life of Brian’ was withdrawn from the Bay’s cinemas after venues across the nation were picketed by Christians. In response, eleven local authorities decided on a prohibition of the movie. A further twenty-eight gave it an ‘X’ certificate which meant that it could be seen only by over-18s. One of these Councils was, of course, Torbay. As the film’s distributors refused to allow it to be shown with an X certificate, ‘Life of Brian’ was effectively banned in the town for twenty-nine years; even though it could be seen on television or by journeying to the more-liberal Newton Abbot.

In 1979 ‘Monty Python’s Life of Brian’ was withdrawn from the Bay’s cinemas after venues across the nation were picketed by Christians. In response, eleven local authorities decided on a prohibition of the movie. A further twenty-eight gave it an ‘X’ certificate which meant that it could be seen only by over-18s. One of these Councils was, of course, Torbay. As the film’s distributors refused to allow it to be shown with an X certificate, ‘Life of Brian’ was effectively banned in the town for twenty-nine years; even though it could be seen on television or by journeying to the more-liberal Newton Abbot.

There will likely always be disagreements about history, identity, symbols, images, rules, and value systems. New zones of combat in the culture wars will be chosen as past themes of so much fierce contention become, for most of us, settled. The divorce rate is now 42 per cent; prime ministers and royalty openly confess to taking drugs; we have, at least in theory, equal pay, equality on gender and sexual orientation; and few disagree that age-appropriate sex education is a good thing.

There will likely always be disagreements about history, identity, symbols, images, rules, and value systems. New zones of combat in the culture wars will be chosen as past themes of so much fierce contention become, for most of us, settled. The divorce rate is now 42 per cent; prime ministers and royalty openly confess to taking drugs; we have, at least in theory, equal pay, equality on gender and sexual orientation; and few disagree that age-appropriate sex education is a good thing.

On the other hand, technology has made censorship unachievable. Pornography, in consequence, is now pretty much instantly available to all, of any age. Not all change is progress.

The Church of England, once Torquay’s moral gatekeepers, now see fewer than 2% of the population at their services. Nevertheless, those old debates on gender and equality have not gone away. But they are now often fratricidal disagreements, conducted amongst the faithful of all religions. Meanwhile, wider society looks on with some sadness and bemusement.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Fleet Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon