During the ‘Swinging Sixties’ Torquay found itself in the frontlines of a series of culture wars.

These were debates between groups and individuals as they struggled for dominance, or just to be heard and recognised, all against a backdrop of an optimistic decade that bled into the more cynical 1970s.

For many the Sixties began as bleak and restricted but by its close some had indisputably gained more liberty and could look forward to a better future. Indeed, it has been said that the Fifties were in black-and-white, while the Sixties were in Technicolor.

Conversely, others saw a decline in morality and standards, and even an erosion of all that civilisation and faith had achieved. In response, the term ‘permissive society’ was used pejoratively by cultural conservatives to criticise what they saw as a breakdown in traditional values and good behaviour.

The disparate offences included movie and television violence and sex, feminism, gay rights, street disorder, swearing, atheism, divorce, and the acceptance of non-traditional relationships. Across the nation, and now in the Bay, old certainties about class, gender and sexuality were being undermined and definitions of a ‘natural order’ challenged.

One noticeable effect was a decline in deference as Torquay saw the emergence of new youth and alternative cultures.

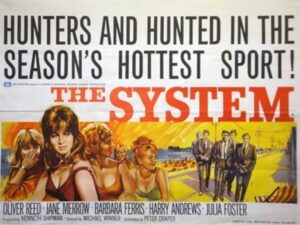

Putting our three towns in the national vanguard of new forms of youth identity and independence was the 1964 movie ‘The System’. Also known as ‘The Girl-Getters’ in the States where it was banned, the film starred Oliver Reed, Jane Merrow and David Hemmings. It presented its Torquay, Paignton, and Brixham setting as a fantasyland of sun, sea and sex; a kind of English San Francisco so different to the hometowns of most cinema-going young people.

Putting our three towns in the national vanguard of new forms of youth identity and independence was the 1964 movie ‘The System’. Also known as ‘The Girl-Getters’ in the States where it was banned, the film starred Oliver Reed, Jane Merrow and David Hemmings. It presented its Torquay, Paignton, and Brixham setting as a fantasyland of sun, sea and sex; a kind of English San Francisco so different to the hometowns of most cinema-going young people.

But it wasn’t the blazer-and-tie wearing young men of the movie that so worried the real-life resort. Partly because of the film, Torquay was becoming home to a new generation of hedonists and alternatives. In the beginning it was the beatniks, followed by the hippies, that embodied an unwelcome transformation of Britain’s premier resort.

In the same year that ‘The System’ was released, Torquay’s Trades Council condemned this new kind of visitor, “Bohemians and their unhygienic habit of sleeping rough on the beaches, in their personal appearance and ganging together to block pavements to pedestrians.”

The 1960s UK government campaign ‘Normal people don’t need drugs’ wasn’t entirely successful

The danger was that the resort would become an “open air doss house”.

“Nothing but harm would come to the name of Torquay from these vagrants… semi-hobos… filthy undesirables… young who shirked the whole responsibility of life”.

At the time, the tourism industry was changing and it was perhaps easier to blame unconventional locals and incomers as agents of degeneration rather than longer-term shifts in consumer demand and taste.

A particular focus of concern was the increasing consumption of recreational drugs in the resort, particularly in the use of cannabis. From then on drug use became deeply symbolic on both sides of a Torquay culture war that went far beyond angry letters to the newspapers.

The Melville, home of the Torquay Beatniks, then the Clipper and now a private home

The original home to the town’s counterculture was the Melville, a pub away from the harbourisde. Then the hippies adopted the Risong Sun, now DT’s.

At 9.30pm on 12 April 1969 seventy members of Torbay’s Drugs Squad conducted a raid on The Rising Sun Inn, now DT’s, on Belgrave Road. This was the first action of its kind and seventeen people were arrested. The raid was a manifestation of a long conflict between the resort’s youth counterculture and the authorities which would culminate in a hundred-strong attack on Torquay Police Station in 1972.

The Rising Sun, which became The Old Mill. Now DT’s, from past landladies Dot & Tracy

Even though the actual peak of domestic holidays taken in Britain was in 1974, the traditional resorts had already begun to face growing overseas competition and from increased car ownership. To fill any widening gaps in trade, something needed to be done and opportunities were sought by both business-owners and the authorities.

For some these measures were to be found in the time-honoured replication of the success of the more-sophisticated Mediterranean resorts. What the continental Rivieras were doing, so could Torquay. But this revived the old argument, to remain upmarket, or to cater for the spending power of the masses.

Always amongst the first provincial towns to import new ideas, Torquay took pride in the title of being a ‘Little London.’ But now the capital’s permissiveness was being seen in a Bay that was becoming increasingly cosmopolitan.

Accordingly, while somewhat looser standards may have always been acceptable in Paignton, a line had to be drawn in the bosom of the Queen of the English Riviera.

The Nationwide Festival of Light’s Cliff Richard and Mary Whitehouse

There had not been an organised backlash to all this change until the launch of the Nationwide Festival of Light, an evangelical campaign opposed to homosexuality, abortion, and other manifestations of the nation’s falling away from God. Its leading lights included the clean-up TV campaigner Mary Whitehouse, journalist Malcolm Muggeridge, and Cliff Richard.

Promoting the Festival in Torquay was the Reverend Harold Smith. In a speech at the 1971 Royal Air Forces Association Annual Battle of Britain service held at Upton Church, Harold linked the fight against Nazism with the imperative to stem the tide of permissiveness. Quoting from a Festival of Light poster, he said that,

“Moral pollution needs a solution. Christian people know where the solution lies. We are concerned at the glorified violence, sadism, incest, and perversion invading public entertainment. Our protest is against all that degrades human dignity and destroys human relationships.”

The contested ground between supposed progress and a disinclination to accept boundary-breaking entertainment was, and had always been, the Harbourside. This was the town’s tourism hub with pubs, clubs, and the grease and glitz of the arcades; the unceasing rise and fall of business enterprises, all chasing the tourist shilling, while in the interstices were the lost and the lonely.

Against this frenetic background, some saw Torquay sliding into decadence, with the Strand and its environs becoming the zone of advance and reaction to a perceived bacillus of licentiousness.

It was here that many skirmishes in the culture wars would be fought.

The nationally-famous Yacht, now coming back to the Harbourside

Taking one example from 1971, we have Ernie Garnham, the larger-than-life landlord of The Yacht on Victoria Parade, putting on strippers to entertain his Sunday lunch time crowd. With some relish, a journalist sent to review the entertainment wrote of how, “Paddy the stripper gyrated her way through the customers.”

In a revealing allusion to how much Torquay had changed from its genteel and sophisticated heyday, Ernie described his objectives:

“I am trying to get the pub known as a place where a bloke can come for a drink and a laugh without being in danger of getting thumped by layabouts. The afternoon starts off with a talent spot. The microphone is passed around to anyone with a joke to tell… In the last show, just before closing time, she takes the lot off. That way everyone stays till the end.”

Ernie Garnham legendary landlord of the Yacht from 1968 to 1980

Provocatively, the journalist ended their article by saying, “None of the customers seemed to see any difference between Sunday and any other day of the week – certainly for a town with so many churches, there were no religious qualms.”

On cue, the Reverend Peter McCrory issued a statement on behalf of the Torquay Christian Council: “Torquay’s many churches appeared largely at a time when Man did aspire to something higher than his purely animal nature. If many still grovel in a lower state of being, then the strip joint and the brothel will continue to flourish as they have done since time immemorial.”

These debates continue in the town today: to stay upmarket or cater for mass tourism; the fine line between individual freedom and irresponsibility; between entertainment and exploitation; the use or abuse of alcohol and drugs; what to build, where to build, and for who.

In essence, what is Torquay, and what does it want to be?

Torquay: A Social History by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Fleet Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon