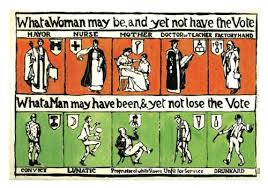

During the campaign for voting rights for women, Torquay had two organisations with differing tactics. These were the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies and the Women’s Social and Political Union. They were to become known as the Suffragists & the Suffragettes.

The NUWSS attempted to convert the public by reasoned argument and through peaceful change. Accordingly, they lobbied politicians, collected petitions and held public meetings. For example, in January 1914 a rally with speakers from all three political parties, titled ‘Why not give women the vote?’, was held at St. Marychurch Town Hall.

The NUWSS attempted to convert the public by reasoned argument and through peaceful change. Accordingly, they lobbied politicians, collected petitions and held public meetings. For example, in January 1914 a rally with speakers from all three political parties, titled ‘Why not give women the vote?’, was held at St. Marychurch Town Hall.

It was organised by the ‘Torquay Branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (non militant and non political)’. The Suffrage Societies deliberately distanced themselves from the Suffragettes who had used militant actions such as chaining themselves to railings, setting fire to post boxes, smashing windows and, occasionally, setting off bombs. The previous year Suffragette Emily Davison had died after she stepped out in front of the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby. Many of her fellow Suffragettes had been imprisoned and had gone on hunger strikes.

It was organised by the ‘Torquay Branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (non militant and non political)’. The Suffrage Societies deliberately distanced themselves from the Suffragettes who had used militant actions such as chaining themselves to railings, setting fire to post boxes, smashing windows and, occasionally, setting off bombs. The previous year Suffragette Emily Davison had died after she stepped out in front of the King’s horse at the Epsom Derby. Many of her fellow Suffragettes had been imprisoned and had gone on hunger strikes.

However, this well-attended meeting saw itself as practical and moderate. The speakers came from all three political parties – Lady Selborne (Conservative), Mrs Alderton (Liberal) and Mr Organ (Labour) – and the arguments in favour of women’s suffrage “were enthusiastically received”.

Beginning the meeting, Lady Selborne believed that, “the old cant of the anti-suffragists that women’s place was in the home was one of the chief reasons why they should have the vote, for the simple reason that the things that concerned the home were better known and understood by women than by men.”

She believed that excluding women from the vote led directly to poverty and the exploitation of women, “Mortality rates in different countries follow exactly the amount of interest and the part taken by women in the political life. The suffrage countries (New Zealand, Australia and Norway) had the lowest infant mortality rates… of disease… and girls were taken better care of. The age of consent was higher, the hours of labour lower and their workshops were more carefully guarded, ventilated and equipped (than in the non-suffrage countries of France, Germany and Italy). In building their cities, the suffrage countries observed far greater care and avoided the slums to be seen all too frequently in England. Would it not be wise for the two sexes to put their heads together and work for the betterment of child life, for the more efficient planning of cities, and for the better provision of housing accommodation?”

She believed that excluding women from the vote led directly to poverty and the exploitation of women, “Mortality rates in different countries follow exactly the amount of interest and the part taken by women in the political life. The suffrage countries (New Zealand, Australia and Norway) had the lowest infant mortality rates… of disease… and girls were taken better care of. The age of consent was higher, the hours of labour lower and their workshops were more carefully guarded, ventilated and equipped (than in the non-suffrage countries of France, Germany and Italy). In building their cities, the suffrage countries observed far greater care and avoided the slums to be seen all too frequently in England. Would it not be wise for the two sexes to put their heads together and work for the betterment of child life, for the more efficient planning of cities, and for the better provision of housing accommodation?”

Mrs Alderton continued the theme of exploitation, “95% of the victims of sweating (hard work done for very low wages) were women. In fact, one in every 5 children died before their first birthday. Parliament was supposed to be representative of all classes, yet in many of the big cities it was impossible for a friendless girl who had nowhere to lay her head, to find refuge, unless she sought the shelter of a house of ill-fame.”

Mrs Alderton continued the theme of exploitation, “95% of the victims of sweating (hard work done for very low wages) were women. In fact, one in every 5 children died before their first birthday. Parliament was supposed to be representative of all classes, yet in many of the big cities it was impossible for a friendless girl who had nowhere to lay her head, to find refuge, unless she sought the shelter of a house of ill-fame.”

Mrs Alderton had attended the House of Commons to hear a debate on women’s suffrage, “but they were too busy to discuss the bill. They were discussing a bill for the protection of crabs and lobsters round the English coast. The crabs and lobsters got their protection years ago – women were still waiting for the vote.”

She knew of an MP, “who declared women should not have the vote because they had not enough physical power. When he rose in the morning he called for hot water which was supplied by a woman; he came down to a breakfast which had been cooked by a woman while he slept; and he left his house by crossing a doorstep that had been scrubbed by a woman hours before he was conscious. He left his house, hailed a taxi and went to the House of Commons to declare that women lacked physical power! Women were asked to pay Members of Parliament £400 each year and these Members voted against their interest.”

Labour’s Mr Organ insisted that, “If women were to work out their social and economic freedom, they must be given their political freedom… There was a great future for this country because of the awakening of its women. It was declared by some politicians that woman’s place was in the home, yet these same politicians, by economic pressure, had driven women into the industrial market, there to exploit her with all the cruelty conceivable… All masculine laws were harsh and unlovely. When women had a voice in affairs, they would then give legislation a touch of practicality and gentility.”

Labour’s Mr Organ insisted that, “If women were to work out their social and economic freedom, they must be given their political freedom… There was a great future for this country because of the awakening of its women. It was declared by some politicians that woman’s place was in the home, yet these same politicians, by economic pressure, had driven women into the industrial market, there to exploit her with all the cruelty conceivable… All masculine laws were harsh and unlovely. When women had a voice in affairs, they would then give legislation a touch of practicality and gentility.”

To convert men to their cause, the NUWSS welcomed male members – in July 1913 Admiral Sir William Acland had motored a Torquay contingent to Exeter to join a large demonstration. The town’s Society also organised missionary-like ‘pilgrimages’ to Totnes, Newton Abbot, Teignmouth and Dawlish. As the NUWSS was supported by a number of prominent members of society – Lady Acland was their Torquay President in 1914 – it was consequently well-funded and able to open offices at 19 Abbey Road.

Torquay’s other suffrage organistaion was the local branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the national movement had been set up by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1903. Their motto was ‘Deeds not Words’, and their tactics became increasingly confrontational. The Daily Mail coined the term ‘Suffragette’ to distinguish these militants from the moderate Suffragists.

Torquay’s other suffrage organistaion was the local branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the national movement had been set up by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1903. Their motto was ‘Deeds not Words’, and their tactics became increasingly confrontational. The Daily Mail coined the term ‘Suffragette’ to distinguish these militants from the moderate Suffragists.

In July 1912, Christabel Pankhurst launched an arson campaign which targeted the houses of MPs and public buildings – Torquay’s police warned that local Suffragettes were planning to burn down holiday accommodation. In response, the Government banned the WSPU’s demonstrations and jailed activists, causing a rapid decline in the Suffragettes’ membership.

In May 1913 a Torquay WSPU meeting was held. The hostile local paper reported that “only a score of women were present to hear Miss Mary Phillips (pictured right), the Devonshire organiser, who does not mince words in her advocacy of militancy”. It was announced that there would have to be “more secret work and they would be more in the position of outlaws”. Also present was the Women’s Tax Resistance League, who refused to pay tax until women received the vote. 220 British women participated in tax resistance – one being a Miss Baker from St Marychurch who had her goods seized by the Torquay courts.

In May 1913 a Torquay WSPU meeting was held. The hostile local paper reported that “only a score of women were present to hear Miss Mary Phillips (pictured right), the Devonshire organiser, who does not mince words in her advocacy of militancy”. It was announced that there would have to be “more secret work and they would be more in the position of outlaws”. Also present was the Women’s Tax Resistance League, who refused to pay tax until women received the vote. 220 British women participated in tax resistance – one being a Miss Baker from St Marychurch who had her goods seized by the Torquay courts.

In June 1914 local Suffragettes took action. Leaflets inscribed ‘Votes for women or ceaseless militancy’ were dropped into Torquay’s pillar boxes along with ink cartridges designed to damage letters. Local Police began to keep close watch on activists.

During the Great War, a serious shortage of able-bodied men led to women taking on many traditional male roles. The Parliamentary acceptance and movement towards women’s suffrage then began. In 1918, Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act, granting the vote to women over the age of 30 who were: householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5, or graduates of British Universities. About 8.4 million women gained the vote. It wasn’t until 1928 than women gained equal voting rights to men.