Back in the fifteenth century, Brixham had an extremely valuable role in the international ‘tourist trade’.

This was our part in the medieval tradition of pilgrimages to holy places.

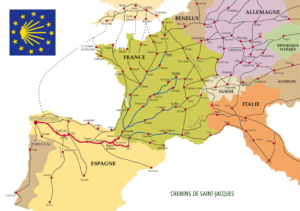

The objective of this specific pilgrimage was to visit the shrine of the apostle Saint James in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in north-western Spain, where, it was believed, the remains of the saint were buried.

The route was the Camino de Santiago – known in English as the Way of St. James – one of the most important Christian pilgrimages during the Middle Ages. The others were to Rome and Jerusalem. It was also a pilgrimage on which an ‘indulgence’ could be earned- this was a way to reduce the amount of punishment one had to undergo for committing sins. Other pilgrims took part to receive an inheritance or as a result of a sentence imposed by a court.

The earliest records of visits paid to the shrine date from the 9th century, but it wasn’t until a century later that large numbers of pilgrims from abroad were regularly journeying there. The earliest records of pilgrims from England were between 1092 and 1105, and by the early 12th century the Spanish pilgrimage had become a highly organised affair taking the devout, and those evading earthly punishment, from across England.

Millions of people from all over Europe made pilgrimages to Santiago. By the 12th century 10 percent of the population of Europe was involved in making or, in some way, supporting the pilgrimage. A Moorish emissary at the time complained of the delays on the road as there were so many pilgrims travelling to, and returning from, the shrine.

This was a very expensive, dangerous and difficult journey.

Pilgrims walked the Way of St. James, often for months or years at a time, to arrive at the great church in the main square of Compostela and pay homage to St. James. The daily needs of pilgrims on their way to and from Compostela were met by a series of hospitals staffed by Catholic orders and under royal protection. Nevertheless, many were lost on the journey, while some pilgrims arrived ill or having been the victims of robbery.

For those returning from Compostela, it became customary to carry back with them a Galician scallop shell as proof of their completion of their journey. This practice led to the scallop shell becoming the badge of a pilgrim.

Getting English pilgrims there became the vocation of the mariners of South Devon.

Pilgrims could only be carried in licensed ships and a petition of 1389 shows that, at that time, pilgrims were only allowed to leave from Plymouth and Dover. Accordingly, from the 14th century Devon’s ports were amongst the earliest to furnish ships for the trade.

It was also a very profitable business and became an important part of English maritime enterprise. Nobles and merchants became involved and ships were chartered by the grantees of licences in London who possessed no ships of their own. For example, in 1391 Dartmouth ship-owner Thomas Ashended obtained a licence to carry 200 pilgrims.

Initially the ships used were those used in trading fish, hides or wine and were not very large. By the 15th century, however, direct transport in larger ships across the Bay of Biscay became the norm. The main Spanish port was A Coruna and merchant ships could carry between 100 and 200 passengers. Nevertheless, the sea journey remained perilous and there were deaths from storms at sea and a lack of clean water and fresh food.

Throughout the pilgrimage period Dartmouth and Plymouth were by far the places that provided most capacity. Yet the demand was more than the two medieval ports could satisfy and it became a much larger enterprise. And so, for more than half a century, Brixham, Topsham, Exeter, Exmouth, Teignmouth, and Portlemouth contributed their ships.

But the pilgrimages weren’t to last. The route was most popular in the first half of the fifteenth century, but then the Black Death and political unrest across Europe led to its decline.

In England the Protestant Reformation condemned pilgrimages as a Catholic practice, viewing the adulation of saints as a form of idolatry. John Calvin further criticised the practices of celebrating relics and creating shrines as not true forms of worship. And so the flow of English pilgrims ended.

Now the pilgrimage has had a resurgence and last year around 200,000 pilgrims walked the route.

Let’s close with a traditional Way of St. James pilgrim song. To encourage one another, pilgrims would greet each other along the way to Santiago de Compostela with ‘E ultreia’ (further) and receive the response ‘E suseia!’ (higher):

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon. Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon. Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us