Nineteenth century Torquay experienced massive change as the town’s population increased from 800 at the beginning of the century to 35,000 in 1900. Rapidly becoming the richest town in England, Torquay was a battleground of ideas and who was triumphant mattered. This was a time when old certainties were being overturned and established authority was being challenged by new social and political movements.

One of the constituent parts of the mosaic that made up the town’s radical tradition were the Methodists.

They were a Protestant Christian denomination which derived their doctrine and practices from the life and teachings of John Wesley.

The title of ‘Methodist’ came from the ‘method’ used to determine their religious convictions. Wesley took an attempted mockery and turned it into a title of honour.

The Methodist movement believed that people should have a very personal relationship with God and that Christians should work with people who need help. Following these beliefs, Wesley attempted to reform the established church from within. But, while the movement did remain as part of the Church of England until after Wesley’s death in 1791, change was resisted and so Methodism separated to become one of England’s nonconformist denominations.

The Methodist movement believed that people should have a very personal relationship with God and that Christians should work with people who need help. Following these beliefs, Wesley attempted to reform the established church from within. But, while the movement did remain as part of the Church of England until after Wesley’s death in 1791, change was resisted and so Methodism separated to become one of England’s nonconformist denominations.

Yet, Protestantism, by its very nature, doesn’t have a central authority and schisms and disagreements on theology and practice are inevitable. And so, Methodism itself saw factions breaking away. The largest of these were the Primitive Methodists.

In 1808 the Methodist lay-preacher, Hugh Bourne, was expelled from the movement. He and his two-hundred followers became known as Primitive Methodists who saw themselves as practising an earlier and purer form of Christianity. Hence the name ‘primitive’ meaning ‘simple’ or ‘relating to an original stage’. From that date the Primitive Methodists were a major movement which persisted until 1932 when the United Methodist Church of Great Britain reintegrated the disparate tradition.

In 1808 the Methodist lay-preacher, Hugh Bourne, was expelled from the movement. He and his two-hundred followers became known as Primitive Methodists who saw themselves as practising an earlier and purer form of Christianity. Hence the name ‘primitive’ meaning ‘simple’ or ‘relating to an original stage’. From that date the Primitive Methodists were a major movement which persisted until 1932 when the United Methodist Church of Great Britain reintegrated the disparate tradition.

The Primitive Methodists differed from Wesleyan Methodists in several ways. They were democratic and locally controlled, as compared with the more middle-class Wesleyan Methodists and, of course, the Church of England.

One distinct dividing line was the Primitive’s encouragement of women evangelists. When the Wesleyan Conference condemned female ministry in 1803, it limited women to working in Sunday Schools and speaking at philanthropic ‘Dorcas Meetings’. This decision made a fracture in the communion inevitable.

One distinct dividing line was the Primitive’s encouragement of women evangelists. When the Wesleyan Conference condemned female ministry in 1803, it limited women to working in Sunday Schools and speaking at philanthropic ‘Dorcas Meetings’. This decision made a fracture in the communion inevitable.

In contrast, all Primitive members were seen as equal and addressed as brother or sister. Even children could participate, and many young people became preachers, including 15-year-olds Elizabeth White and Martha Green.

Primitives were visible, noisy, spontaneous, and passionate. They made use of revivalist techniques such as open-air preaching and told of damnation, salvation, sinners and saints. All was seen as seditious evangelism by the established church. In 1799, the Bishop of Lincoln went as far as demanding that the ‘ranter’ element of Methodism was so dangerous that the government should ban it.

It was also this kind of “fanatical zeal” that mainstream Wesleyan leaders found so embarrassing, even more so during a time when they were striving to be seen as respectable members of Torquay society.

Of particular note was the Primitive Methodist base among the poorer folk, and we accordingly see a disparity in the wealth and social position of congregations. Wesleyans were often from a lower middle class or artisan background, while Primitive Methodists were most likely to be small farmers, servants, agricultural labourers, weavers and framework knitters.

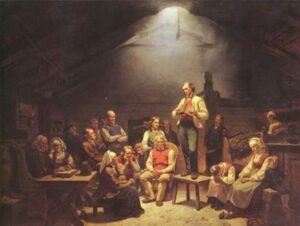

It was the Primitives’ passion, enthusiasm and fervour that attracted many of the most disadvantaged in the resort. The hymns they sang were influenced by local culture and sung to popular tunes in contrast to the “more staid hymns sung in Wesleyan chapels”. Wesleyan services were, it was claimed, less in demand as they were “embellished with literary allusions and delivered in high-flown language”.

Primitive Methodist preachers, in consequence, were often less educated, included both women and men, were of all ages and social classes, and so more likely “to be at one with their congregations” or even “dominated by them”. They were consciously plain-speaking and wore unpretentious clothing, believing that simplicity was supported by the Gospel. But this approach was also consciously designed to make them distinctive. Primitive Methodist wanted to stand out and be seen as a “peculiar people”.

Appropriately, bearing in mind the Primitives’ commitment to plainness, their chapels were marked by an unpretentious design, compared with Wesleyan churches. A poor congregation led to constraints on income and further necessitated that their buildings be situated in the less affluent parts of town, the back streets, and away from Torquay’s main thoroughfares.

Appropriately, bearing in mind the Primitives’ commitment to plainness, their chapels were marked by an unpretentious design, compared with Wesleyan churches. A poor congregation led to constraints on income and further necessitated that their buildings be situated in the less affluent parts of town, the back streets, and away from Torquay’s main thoroughfares.

The first local Primitive Methodist society was founded in Babbacombe in 1863 and worship took place at Kingsway Hall which opened in October 1868.

In Torquay itself, the Primitive Methodists first held their meetings in a prayer room in Union Street. They then acquired an old Baptist Chapel in Temperance Street in 1863. That building is now occupied by the Torbay Community Cafe and Help Hub.

In Torquay itself, the Primitive Methodists first held their meetings in a prayer room in Union Street. They then acquired an old Baptist Chapel in Temperance Street in 1863. That building is now occupied by the Torbay Community Cafe and Help Hub.

In 1877 the Primitive’s purchased a large house in Ellacombe and the following year opened the Market Street Primitive Methodist Chapel. A hall and other ancillary buildings were later added at the rear.

Local photographer James Dinham oversaw the Chapel’s music. It is James that we have to thank for a series of illuminating and now familiar photographs of the residents of nearby working-class Pimlico. Each photograph has a witty or informative title and shows the real lives of residents so far distant in experience from the town’s villas and hotels.

During the 1970s dry rot was discovered in the Market Street Chapel and there were ongoing issues with the heating system. This caused the chapel to be abandoned in 1973. The Market Street site was sold, and the building demolished, to be replaced by an apartment block. The congregation then joined the Union Street Chapel while some of the money released was used to help build the new Central Church which opened in 1976.

During the 1970s dry rot was discovered in the Market Street Chapel and there were ongoing issues with the heating system. This caused the chapel to be abandoned in 1973. The Market Street site was sold, and the building demolished, to be replaced by an apartment block. The congregation then joined the Union Street Chapel while some of the money released was used to help build the new Central Church which opened in 1976.

And so was lost yet another of Torquay’s churches and chapels. So many have been demolished or converted into apartments and workplaces. It seems likely that more will follow.

In 2011 there were 82,924 self-declared Christians in the Bay; 62% of the population. By 2021 this had fallen to 67,634 (49%). And so, year-by-year, in most denominations, the congregations age and slowly but surely vacate those monuments to long-forgotten disputes over doctrine and practice in the Torquay townscape.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon