In the late nineteenth century, Torquay was the richest town in England. Many millionaires lived or visited the town. However, amidst this wealth and sophistication Torquay folk who were unable to provide for themselves could find themselves in Newton Abbot’s Workhouse.

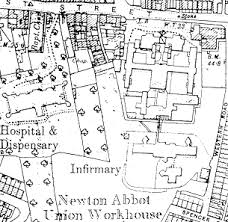

The 1834 New Poor Law had altered the system from one which was administered at a local level to a centralised system which encouraged the development of Workhouses by Poor Law Unions. Thus, the Newton Abbot Poor Law Union was formed in 1836 and their Workhouse, which could accommodate 350 inmates, was built in 1837 in East Street – around where the new Sainsbury’s is now and pictured below. The desperately poor of all ages, the mentally ill, and disabled were, for decades, transported out of Torquay to a place where they would not offend tourist sensibilities. Our most vulnerable were sent away and hidden from view.

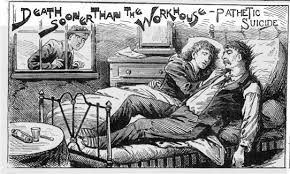

Workhouses were made deliberately unwelcoming and harsh. They needed to be as conditions were so awful for many people in Torquay with disease and starvation commonplace. They had to be seen as a last resort and even the starving and dying avoided them. Not surprisingly abuse was common. Indeed, there was a terrible scandal at Newton Abbot Workhouse in 1894.

It was found that a strait-jacket, called a ‘jumper’ was being used, and that elderly paupers had been placed in it naked, and then tied to beds. This had led, it was alleged, to the deaths of some inmates. Witnesses described that the wards were filthy, and the inmates infested with vermin. Food was kept in the lavatories. Another witness said she saw two men tied to the same bed.

A nurse testified that she had found a female inmate dying, her hair had been cut off, and her toe-nails were like claws. A paralysed inmate had injured herself with her uncut finger-nails. Another nurse said she had been given sole charge of 150 ill paupers. Sick children were under the care of two partially blind women. One child had been tied to a bed with string to prevent it from running about as it had no shoes and stockings. Eleven children had four nightgowns between them.

A woman with, what we would now call, learning disabilities was observed in the workhouse yard crouched in a corner with a bruised face. A shed had been built for her in the yard but boys, including the master’s son, threw stones and snowballs at her. Fighting amongst the inmates – who were described as “idiots” – was commonplace. What seems to have been particularly shocking to the devoutly Christian inspectors was the “immorality” of those confined.

The matron for almost thirty years, Ann Mance, was accused of neglecting her duties, dismissed, and died from a heart condition a few weeks later.

Nevertheless, the workhouse remained in use for decades. By the time of a Torquay Times visit in 1928, it was now called the Newton Abbot Union Institution – the term Workhouse had by then become tainted. The newspaper’s correspondents reflected society’s view that the very poor should be punished as well as supported: “The pauper suffers in a general sense for the improvidence of which he has been guilty, exactly as a criminal expiates his wrong doing behind bars.”

These ‘inmates’ had their freedom tightly restricted: “What hurts the bulk of the inmates is the confinement. There are some inmates who very rarely, if ever, go outside the walls… With some of them melancholia is engendered, and eventually become anything but normal. The tempers become deranged.” In effect, if you didn’t have a mental illness before you entered the workhouse, you would soon acquire one.

Workhouses were only officially abolished by the Local Government Act of 1929, but many persisted into the 1940s. Workhouse buildings, such as the one in Newton Abbot, were then widely re-used in the National Health Service.

Outside of the workhouse the desperate turned to charity. For example, in 1895 the charitable Torquay Mendicity Society estimated that: “There are at least 200 men who have no work to do, and many of them have wives and families dependent upon them. The districts feeling the pinch most are Ellacombe, Torre, Upton and Melville Street. Amongst the fishermen too, great distress prevails. The Market Corner has been a kind of barometer by which one can tell the condition of the labour market and large numbers of men, anxious and willing to work, if they could get employment, have assembled there.” Pictured below are some local residents in around 1890.

In February of 1895 a correspondent from the Torquay Times visited a soup kitchen in Market Street. He described how soup was given out to 500 local people: “And now Mrs Gibbs and Mrs. Wreyford, with turned up sleeves and armed with large enamelled cups, mount guard… Then arrived the children, some with milk cans, some with milk jugs, and some with even washstand jugs. And now the crush has become so great. An old man leaning tremulously on a stick is seen approaching the table. Here comes an old lady who is bewildered by the rush. Then come the mothers, some respectably clad, and evidently experiencing that mortification at receiving charity with which we can all sympathise, and others with torn garments and dishevelled appearance”.

Coordinating this relief was the Torquay Charity Organisation Society which was launched in 1886 and which covered Torquay, St Marychurch and Cockington. From their premises at 10 Abbey Road – opposite Ryans Bar and pictured below – the COS took on a range of tasks. They helped the old and the “thoroughly respectable poor” avoid the workhouse – in the first year 73 poor people were assisted and 30 refused. They sent children to orphanages, and gave money, food, dentures, surgical appliances and hospital tickets to the needy. Unemployed people were helped to emigrate to Canada, and “mentally defective persons” were assisted.

While providing support for the “really deserving poor”, there was also recognition that the desperate could become dangerous – the COS would “improve personal sympathy between the rich and poor which would bridge over the unfortunate chasm which separated them and which had become a national peril”.

Yet a continuing theme was the Victorian obsession with separating off the poor into two classes, the ‘deserving and ‘undeserving’.

By 1904, the society was insisting it had been successful in its task of, “elevating the deserving poor by suppressing the haphazard harmful charity existing in Torquay… Torquay people had, thanks to the society, grown wiser since the day when, by tramping around the hills and pulling the bell at the doors of villas, a man or woman could receive any amount of half-crowns”.

However, despite the COS’ efforts, indiscriminate charity clearly continued. In 1911, they reported that tramps and beggars “still present one of the most difficult problems in Torquay”. In response, they produced a leaflet to discourage “rich people on the hills” from giving to beggars without enquiry.

In 1930 the town’s rising population and the continuing need for the coordination of services led the COS to become the Council of Social Services. It then became Torbay Voluntary Services and is now Torbay Community Development Trust, the umbrella organisation supporting the Bay’s more than 600 local community groups.