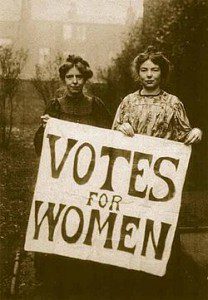

Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst

Torquay has always had a small number of residents who have asked awkward questions of established authority. Even before our small scattered communities came together as a town we seem to have produced troublemakers.

During the English Civil War (1642–1651), for example, the Royalist commander Prince Maurice (pictured below) found it necessary to write to Colonel Edward Seymour of Torre Abbey about, “Diverse persons disaffected to His Majesty’s service and peace of the Kingdom do associate and meet together about Torbay in a hostile manner to the great terror and distraction of His Majesty’s loyal subjects…I authorise you, for the suppression of which insurrection to repair with your force to Torbay… there to repress and reform the same, and in the case of opposition or resistance to slay, kill and put to execution of death by all ways and means.”

Trouble flared again in town in 1847 when rising prices caused real distress to the working class and Bread Riots broke out. On May 17 a Torquay mob ransacked bakers’ shops in lower Union Street, “the contents of which were carried off by the women in their aprons”. Several thousand rioters then raided shops in Fleet St and Torre, and fought with local traders. A number were arrested, but the rioters demanded their release – 60 navvies from the railway works at Torre armed themselves with “pick axes, crow bars and shovels, with the avowed purpose of pulling down the Town Hall”. To restore order, a revenue cutter, the Adelaide, and a government steamer the Vulcan brought a detachment of coastguards. Forty troops arrived from Exeter while 300 special constables were sworn in. Eventually, 27 rioters were jailed, though these prisoners had to be sent to Exeter by sea, instead of by road, as a plot to rescue them had been discovered.

Torquay saw a further Bread Riot in 1867. Men rolled tar barrels and attacked shops till 5am, and an attempt was made to sabotage gas supplies. It seems as if this was well-organised: “Much brutality was exhibited by the mob, the women bringing supplies of heavy stones from Ellacombe; these were aimed at the constables, and many were severely wounded”.

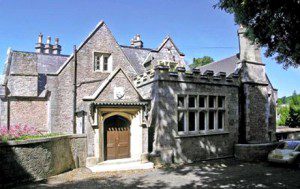

Another form of dissent came from Christians who had found themselves outside of the Anglican Church. One good local example is of the Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers, who were unusual in that they permitted ministry to be given by both men women, had no paid clergy and rejected social hierarchies. Quakers have long been involved in action aimed at promoting social justice and equality, including participating in the anti-slavery movement, in prison reform and the women’s rights movement. The Quakers first came to Torquay in the 1830s and in 1955 they bought Tor Hill Lodge in Tor Hill Road (below), this Meeting House remaining a focus of the Bay’s Quaker activity. The Quakers maintain their proud tradition of advancing good community relations and to this day host meetings of the Torbay Inter Faith Forum.

The radical Christian challenge to established authority came to a head in 1888 when the Salvation Army arrived in town. In January 1888 Torquay police charged a Salvation Army band with illegally parading on a Sunday. The Corps Commander, the bandmaster and several bandsmen were fined, but refused to pay and were jailed. On February 3, 11 more were summonsed for the same offence. A pattern then emerged. The bandsmen played every Sunday, and were then summonsed. A regular event was the musical procession that accompanied prisoners being taken to Exeter prison, and to welcome them on their return. Over 100 were eventually prosecuted and often imprisoned. In response, sympathisers formed a bodyguard to protect the Salvationists (that’s 24 year old Evangeline Booth pictured below) from the police and from hostile locals.

Over the months, the Army was reinforced by bandsmen from across Devon. In a cat-and-mouse game, the police responded with surveillance, infiltration, intimidation, and – according to reports – the occasional violent assault. Meanwhile, taking advantage of the confusion, young men engaged in “rowdyism and riot”. By the end of the year the Salvation Army had prevailed and local laws were changed.

Incidentally, it’s worth noting that attempts by the mainstream Church to retain control and to ensure social order continued for another century – as late as 1979 the Church could still put pressure on the Council to ban Monty Python’s Life of Brian.

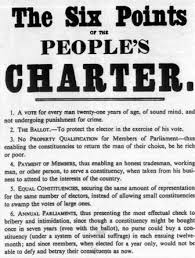

Other local people found reason for dissent in the lack of democracy in England. This activism took the form of Chartism, a movement for political and social reform between 1838 and 1850. The name came from the People’s Charter of 1838, which stipulated six main aims: a vote for every man over 21 years of age; a secret ballot; no property qualification for members of Parliament so anyone could be an MP; payment of MPs; equal-sized constituencies; and annual parliaments to make MPs responsive to their constituents.

Chartism was probably the first mass working class labour movement in the world and the Chartists were active in Torquay. We can get an idea of how they were perceived by Torquay’s gentry from the several reports of a Chartist meeting that was held in September 1846. The reports of the event suggest that the Chartists had to disguise their activities as attempts to rent meeting rooms were refused. Hence, the Temperance Hall was booked for a less-provocative purpose, yet, “The Lecture soon degenerated into a coarse Chartist declamation, the Lecturer endeavouring by exaggeration and calumny, to poison the minds of the ignorant against every institution, social and political, by which, under the blessings of providence, the industrious classes of this country have so long been raised above those of every nation upon earth… Is it possible that any who call themselves Christians can ally themselves with such as this – can advocate rebellion and civil war as lawful means for overthrowing the powers which are ordained by God?”

Unfortunately, we don’t know much more about those Chartists who caused so much concern to Victorian Torquay, or if any of those attending the meeting were involved in Torquay’s Bread Riots the following year.

Though the Chartists failed to convince Parliament to reform the voting system at the time, the ‘Agitators’ were ultimately successful: five of the six points in the Charter were adopted by 1918.

Dissenters didn’t always come from the poorest sections of society and radicals often found allies amongst our local elite. One notable philanthropist was Edward Vivian (1808-1893) who has an association with a town centre cafe. This is the building (pictured below) which was built as the Salem Chapel in 1839. In 1887 it became the School of Science and Art, and then the Vivian Institute where working men could attend evening classes in carpentry, joinery, painting, stonemasonry and turning. They paid 2 shillings a month and received three two-hour lessons a week.

Though Edward was a Liberal, taking the side of the Salvation Army when they were being jailed in 1888, he believed that existing political structures were largely correct and opposed the secret ballot and the universal franchise. Yet, he was involved with many philanthropic campaigns and it was his practical solutions to poverty that brought him into contact with local Chartists.

By the 1840s the Chartist campaign for electoral reform had been frustrated by jailings, failed armed uprisings and intimidation. In response, in 1843 parts of the movement had moved away from demonstrations and violence and established the National Charter Association, “to provide for the unemployed, and give means of support for those who are desirous to locate upon the land”.

At its peak, the National Charter Association had 70,000 shareholders and 600 local branches, one of which was in Torquay. In 1848 Edward let ‘allotments’ of his land at his house ‘Woodfield’ in Lower Woodfield Road (right) to 16 members of the National Charter Association. The aim was to encourage everyone to grow their own food, and eventually 38 quarter acre plots were set up in the Lincombes. However, the experiment in land reform failed. Many of the smallholders had little or no experience of agriculture and no idea of how to make their allotments a success.There were also better wages to be had in industry or in service.

Nevertheless, the Chartists and their philanthropist allies are part of a long tradition of taking land into group ownership and of – what we now call – lifestyle politics. Such practical strategies are to be seen in today’s Green movement.

Despite the suppression of the Chartists, the demand for democracy continued and in the Reform Act of 1867 real progress was made. This was a piece of legislation that gave the vote to the urban male working class enfranchising about 1,500,000 men – a significant and symbolic extension of democracy.

However, there was real resistance to change and the Act only came about after a long struggle. Leading the demand for universal suffrage was the Reform League which organised demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of people in cities such as Manchester and Glasgow. One of the smaller towns that held major demonstrations was Torquay.

On January 1, 1867, “the working men of Torquay, with the guidance of the Reform League, turned out en masse” in a 1,000 strong demonstration and rally. They marched through “the principal streets in the lower part of the town and Torre back to Ellacombe Green. The streets were lined with spectators, and at some of the houses flags were hung out, showing the sympathy of the occupiers”.

The march comprised of activists of the Reform League and contingents of local workers: The Sawyers (sawers of wood), Plasterers, Carpenters, the Torquay Tailors Association, the Boot and Shoe Makers, the Brass and Iron Founders, the Gardeners, and many others. Each contingent was led by a banner, often with an appropriate message: the Painters had “Our Colour Shall be Bright” while the Cabinet Makers had “A New Cabinet for the People”.

Providing the musical accompaniment to the march were local bands: the Torquay Subscription Band, the Paignton Artillery Band, The Torquay Rifle Band and the Torquay Artillery Band – whose banner proclaimed “Our Aim is the Country’s Good”. The demonstration came marching in to Ellacombe Green, “at 1 o’clock and in an hour they had marshalled in their respective position with banners flying and bands giving out inspiriting tunes”.

Working people had often been described as uneducated, or too lazy or drunk to care about how they were governed. The Reformers denied this and the following resolution was carried unanimously by those on Ellacombe Green:

“That this meeting enters its solemn protest against, and its denial of, the charges of venality, ignorance, drunkenness, and indifference to Reform, brought about against the working classes during the late session of Parliament, and hereby declare that no Reform Bill falling short of the principles of registered residential manhood suffrage, and the ballot, will be satisfactory to the people, or accepted as a final settlement of the Reform question.”

Demand for the vote continued and in May 1867 a demonstration was planned for London’s Hyde Park. It was banned by the government and thousands of troops and policemen were prepared. However, the crowds were so immense that the government dared not attack. Due to this humiliation, the Home Secretary, Spencer Walpole, was forced to resign. Then, faced with the possibility of popular revolt, the government accepted the Bill and working men achieved the right to vote.

There would be many more demonstrations and acts of protest over the following decades before every adult in Britain had the right to participate in our democracy. The part that Torquay folk played should not be forgotten.