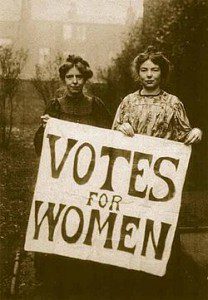

While many of Torquay’s men acquired the right to vote in 1867, women were still excluded. In 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst was so frustrated by the lack of progress towards women’s suffrage that she founded the Women’s Social and Political Union. The motto of the WSPU was ‘Deeds not Words’. In July 1912, Christabel Pankhurst began organising a secret arson campaign and attempts were made by Suffragettes to burn down the houses of members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards a house being built for Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by fire.

In 1913 the WSPU arson campaign escalated and railway stations, cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses were set on fire. In Torquay police warned that Suffragettes were planning to target coastal resorts and burn down holiday accommodation.

In May 1913 a Torquay WSPU meeting was held at the Museum Hall. “A score of women” heard an announcement that, “there would have to be more secret work and they would be more in the position of outlaws than they were before”. One form of this more direct action took the form of refusing to pay tax until women received the vote. Across Britain, more than 220 women participated in tax resistance between 1906 and 1918 – one of these was a Miss Baker of St Marychurch who had her goods seized after a hearing at Torquay Town Hall.

The real “secret work” proposed by Torquay Suffragette Mary Phillips came about in June 1914 when the town’s pillar boxes were vandalised. “Votes for women or ceaseless militancy” was inscribed on envelopes which were dropped into pillar boxes at Upton, the Strand, Torwood Gardens, Castle Circus, Forest Road and elsewhere. The Suffragettes had put ink cartridges in the envelopes to damage other letters. In response, the Police were tasked with preventing a repeat of the vandalism and they kept watch on local Suffragettes.

Though this sounds trivial, this wasn’t an easy struggle for many of those involved. Let’s take Torquay’s Suffragette Organiser Elsie Howey (1884-1963). Elsie, “in the vanguard’ of militancy”, (pictured left) was imprisoned at least six times, went on hunger strike and was force fed on a number of occasions. It was in March 1909 that Elsie was appointed as the WSPU organiser in Torquay and Paignton, and opened a WSPU shop in Abbey Road. When she ended one 144 hour hunger strike she was presented with a travelling clock by Torquay’s Suffragettes. Elsie was also involved with other Suffragettes in assaulting Herbert Asquith and Herbert Gladstone while they were out playing golf.

During Elsie’s hunger strikes she was force fed. This broke most of her teeth and her health suffered greatly. She never fully recovered from her treatment by the authorities.

In the end these sacrifices made a difference. Women were partly enfranchised on February 6, 1918. The Representation of the People Act gave the vote to women over 30 who “occupied premises of a yearly value of not less than £5″. But it was not until 1928 that the voting age for women was lowered to 21 in line with men.

While political beliefs have always divided opinion in Torquay, after the Second World War came divisions based on age and lifestyle. This became known as the Generation Gap which emerged during the 1960s to refer to differences between people of a younger generation and their elders.

While political beliefs have always divided opinion in Torquay, after the Second World War came divisions based on age and lifestyle. This became known as the Generation Gap which emerged during the 1960s to refer to differences between people of a younger generation and their elders.

This was particularly acute in towns that attracted large numbers of young people. For example, in September 1964 the President of Torquay Trades Union Council complained that, “I did not think that in the 20th century we would have people who would walk about literally stinking.” The unions went on to condemn, “Bohemians and their unhygienic habit of sleeping rough on the beaches, and lounging on street corners, wearing al fresco attire and no shoes and ganging together to block pavements to pedestrians. The holiday season had always attracted a small number of the begging fraternity… now there were more requests from unshaven shabbily dressed and unwashed gentlemen for the price of a glass of coffee. They sleep under the stars or under carefully-erected Corporation deck chairs, the Beacon Quay car park or on the tow path seats flanking the harbour.”

In the early 1960s the focus of trades union hostility were the Beatniks. The original Torquay Beatnik pub was The Clipper in Melville Hill, (pictured left) focus of the alternative music and poetry scene. The most famous product of which was Donovan who lived on Abbey Road. Here’s Donovan’s first hit song written in that Torquay bed-sit in 1965:

In the early 1960s the focus of trades union hostility were the Beatniks. The original Torquay Beatnik pub was The Clipper in Melville Hill, (pictured left) focus of the alternative music and poetry scene. The most famous product of which was Donovan who lived on Abbey Road. Here’s Donovan’s first hit song written in that Torquay bed-sit in 1965:

A group of Beatniks – a kind of an early type of hippie – visited the Torquay Times office to defend themselves. They were described as, “well spoken and intelligent”, and complained that they had been banned from most cafes and made to sit outside pubs. In their later teens and early 20s and originating in Scotland, London, Liverpool and Derby, they explained, “We do wash… Our clothes may be dirty but it’s the sensible attire to wear walking around. We chose to live this way and we keep ourselves to ourselves and not get involved with other people. We reject society and try to assert ourselves as individuals.”

One issue of the young has always caused divisions – the use of illegal drugs. In early 1969 Torbay’s Police issued a statement saying they were keeping an eye on “local hippies”. A Paignton chemist had been burgled and a large amount of drugs was stolen, it was assumed for resale. South Devon’s pub landlords had also been warned to be on the lookout for anyone smoking “oddly shaped cigarettes”.

Since the mid-60s, Torquay’s main hippie pub had been the Rising Sun on Belgrave Road (now DTs Bar and pictured above in an old photo). At 9.30pm on April 12, 1969 around 70 members of the Torbay Drugs Squad conducted a drugs raid with a warrant to search anyone. This was the first raid of its kind in the Bay. Some 17 people were arrested – 16 for possession under the Dangerous Drugs Act and one for wilfully obstructing the police.

In early 1970 the police  told the press that Torbay had a small drugs problem among residents, but in the summer this could increase by 50 to 60% because of the influx of visitors. “The drug takers are mostly young people coming down here because it is a nice place. There is plenty of accommodation and they can get casual jobs in bars, holiday camps and hotels.”

told the press that Torbay had a small drugs problem among residents, but in the summer this could increase by 50 to 60% because of the influx of visitors. “The drug takers are mostly young people coming down here because it is a nice place. There is plenty of accommodation and they can get casual jobs in bars, holiday camps and hotels.”

In March 1970 an anonymous 21-year-old spokesman for the town’s resident hippies claimed that the police were, “harassing them in order to break up the community before the influx of summer visitors. They are also tightening up on the places where we meet – trying to get them to close down or to refuse to serve us. They are using the stop-and-search powers more. They’ll stop anyone who dresses differently or who has long hair. They’re really leaning on the communities… There is a paranoia in Torbay among the establishment about the alternative lifestyle which they don’t understand… I suppose if enough people thought the way we do, we would be a threat to the system.”

Incidentally, it’s been suggested that towns that are dependent on tourism develop a particular intolerance of any non-standard beh aviour that could ‘frighten off the visitors.’

aviour that could ‘frighten off the visitors.’

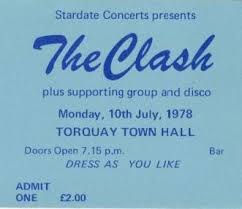

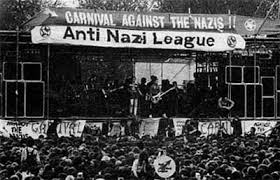

The next generation of young rebels came in the form of punk rock. For many, punk wasn’t just about the music. It was a political movement. It was anti-racist, welcoming of gay people, and also feminist with women forming their own bands and identities. Local punks were often anti establishment, rebelling against what they saw as an old-fashioned town with repressive attitudes. Specifically, local punks saw the threat posed by the rise of the far right in the form of the fascist National Front – in 1978 a coach load from Torbay journeyed to the East End of London to join 80,000 others at the Rock against Racism Festival.

The next generation of young rebels came in the form of punk rock. For many, punk wasn’t just about the music. It was a political movement. It was anti-racist, welcoming of gay people, and also feminist with women forming their own bands and identities. Local punks were often anti establishment, rebelling against what they saw as an old-fashioned town with repressive attitudes. Specifically, local punks saw the threat posed by the rise of the far right in the form of the fascist National Front – in 1978 a coach load from Torbay journeyed to the East End of London to join 80,000 others at the Rock against Racism Festival.

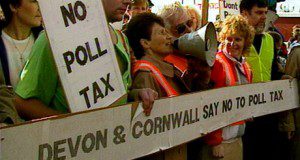

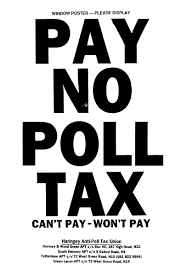

Yet it wasn’t from the young that the next Torquay protest movement came. This, surprisingly, came from the introduction of a new system of local taxation in 1990 – which acquired the name of the Poll Tax. Many people thought this new tax was unfair as they believed that it shifted the tax burden from the rich to the poor.

The Poll Tax in Torbay was the highest in the West Country. An indication of the strength of local feeling against the Poll Tax in Torbay came about in early 1990 when an anonymous group of local radicals issued a leaflet: “We produced 50 copies of a leaflet called ‘Smashing the Poll Tax in Torbay’. It gave instructions on how to avoid paying the Tax, how to beat the bailiffs, how to drag out court appearances… We really thought that half a dozen Punks in Ellacombe would be interested. We left the leaflet in phone boxes and pubs. A week later people would come up to us and say ‘Have you seen this?’ It was being copied all over the Bay. We even heard that it was being illicitly copied by Council staff on Council photocopiers and given to their family members!”

Poll Tax in Torbay’. It gave instructions on how to avoid paying the Tax, how to beat the bailiffs, how to drag out court appearances… We really thought that half a dozen Punks in Ellacombe would be interested. We left the leaflet in phone boxes and pubs. A week later people would come up to us and say ‘Have you seen this?’ It was being copied all over the Bay. We even heard that it was being illicitly copied by Council staff on Council photocopiers and given to their family members!”

By February 2,000 locals had refused to pay. The Torbay protest escalated and in mid-February a group of what the local media dismissively called “housewives” formed the ‘Axe the Poll Tax’ organisation and set up a petition and planned a demonstration.

The ‘Axe the Tax Rally’ on March 17 began with feeder marches from across the Bay. The Torquay March set off from Kings Drive with 250 demonstrators – “hundreds of passing drivers hooting their horns in support”. They carried 11,500 signatures on a petition gathered in Torquay alone. This was the largest demonstration Torbay had ever seen: 5,000 people, “ranging from grannies to babes in arms”. The police superintendant in charge of the security operations admitted he was struck by how the demonstrators were “just ordinary people”. Remarkably, Torbay activists had gathered a petition of 35,000 signatures, around a third of the total population.

The ‘Axe the Tax Rally’ on March 17 began with feeder marches from across the Bay. The Torquay March set off from Kings Drive with 250 demonstrators – “hundreds of passing drivers hooting their horns in support”. They carried 11,500 signatures on a petition gathered in Torquay alone. This was the largest demonstration Torbay had ever seen: 5,000 people, “ranging from grannies to babes in arms”. The police superintendant in charge of the security operations admitted he was struck by how the demonstrators were “just ordinary people”. Remarkably, Torbay activists had gathered a petition of 35,000 signatures, around a third of the total population.

Such an outpouring of dissent came from nowhere. Ordinary people joined the permanently dissatisfied minority who were always there asking questions and consistently being plain awkward. Such is the history of dissent in Torquay. We don’t know what the next cause of dissatisfaction is going to be, or the next demand for change, but Torquay’s radicals can get it right and contribute to real social change…

Such an outpouring of dissent came from nowhere. Ordinary people joined the permanently dissatisfied minority who were always there asking questions and consistently being plain awkward. Such is the history of dissent in Torquay. We don’t know what the next cause of dissatisfaction is going to be, or the next demand for change, but Torquay’s radicals can get it right and contribute to real social change…