The English Riviera website assures visitors that “the warmest of welcomes awaits on the English Riviera, South Devon’s Beautiful Bay.” Yet, some past visitors haven’t enjoyed their visit as much as they should have done.

Indeed, the locals can sometimes be a bit unfriendly.

In 1750 the brig St. Peter was wrecked “about a mile west of Torre Abbey. Immediately, the country people came down to plunder the wreck and even robbed the captain of his watch.”

A year later the wreck of a French vessel under Waldon Cliff almost led to a battle between the locals of Torre and the Torwood estate. Waldon Hill was Cary ground, but the Torwood men came along from the harbour with the local customs officer and did “much pillaging and wanton damage”. The Cary steward strengthened his forces by recruiting half a dozen men from the neighbouring Cockington estate and discouraged the Torwood folk from carrying on their thievery. We don’t know what happened to the French sailors while the locals were pillaging their ship.

As is the case today, Torquay was growing rapidly in the nineteenth century. Author Mary Anne Evans (1819-1880) is better known by her pen name George Eliot (pictured above). She visited Torquay in 1868 and wasn’t that impressed with its overdevelopment:

“I don’t know whether you have ever seen Torquay… It is sadly spoiled by wealth and fashion, which leaves no secluded walks, and tattoo all the hills with ugly patterns of roads and villa gardens… Everywhere houses and streets are being built, and Babbicombe will soon be joined to Torquay… We should not come again without special call, for in a few years all the hills will be parts of a London suburb.”

However, once she returned home, she had mellowed a little and admitted in a later letter, “…we became deeply in love with Torquay in the daily heightening of spring beauties, and the glory of perpetual blue skies.”

When Canadian Isabella Cowen visited in the 1890s she found it rained a lot: “Torquay weather outdoes anything else I have encountered in the way of fickleness. The explanations and apologies for the state of the atmosphere are getting to be a very monotonous theme of conversation.”

As a health resort, the town had a high population of the sick and disabled:

“Torquay has a seeming monopoly of invalids. Some days I found the pleasure of our walks along Rock Walk and the sands perfectly destroyed by the number of infirm old people and still more lamentable, deathly looking young people who haunt that particular place of pleasure.”

We also had a fondness for alcohol with locals and visitors being drunk at all times:

“Intemperance is too common a vice here and too fruitful of the misery both here and elsewhere to be made light of… As long as an Englishman can keep upon his feet he is considered quite respectable.”

The children’s author Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) came from an affluent family which had the resources to travel extensively. The Potters would leave their Kensington home for several weeks to allow their servants to tackle the spring-cleaning. In March 1893 Beatrix (above) visited Torquay. She found her accommodation unsatisfactory:

“I didn’t much want to go. I did not take to what I had seen of Torquay… I sniffed my bedroom on arrival, and for a few hours felt a certain grim satisfaction where my forebodings were maintained, but it is possible to have too much Natural History in a bed. I did not undress after the first night, but I was obliged to lie on it because there were only two chairs and one of them was broken.”

Anstey’s Cove was “curiously pretty but rather too much of a show place”, while St. Marychurch was “a most dreary suburb”. Then came the turn of Kent’s Hole – which we now call Kent’s Cavern: “I can imagine no more unlikely or unromantic situation for a cavern. It is in a suburb of Torquay, half way up a tangled bluff, with villas and gardens overhanging the top of a muddy orchard with some filthily dirty cows in the ravine below…”

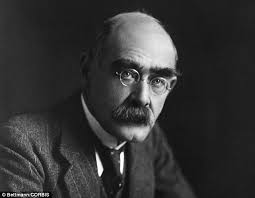

Even invisible locals could be a little hostile to outsiders. In 1920, the writer Beverley Nichols (pictured above), his brother and a friend, Lord Saint Audries, visited Torquay’s version of Amityville, ‘Castel a Mare’ in Middle Warberry Rd. The three ghost hunters were violently assaulted by unseen spirits. The supernatural similarly affected Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) who lived in Maidencombe’s Rock House in 1896. Rudyard also took a dislike to Torquay’s conservatism: “Torquay is such a place as I do desire to upset it by dancing through it with nothing on but my spectacles. Villas, clipped hedges and shaven lawns, fat old ladies with respirators and obese landaus.”

Yet, it was Rock House itself that really disturbed Rudyard (pictured above). He began to complain about “a gathering blackness of mind and sorrow of the heart” whenever he entered. Even thirty years later when he revisited Rock House, it was “quite unchanged, the same brooding spirit of deep, deep Despondency within the open, lit rooms”.

Perhaps some locals can be a bit judgemental. Arnold Ridley was an actor, writer, and a Torquay schoolmaster. However, he is probably best known for his role as Private Charles Godfrey in the 80 episodes of the TV series Dad’s Army which ran from 1968 to 1977. Ironically, Arnold played the only conscientious objector in the Home Guard platoon of Walmington-on-Sea – yet, he fought for more than a year on the frontline during the Great War. He went ‘over the top’ at the Battle of the Somme, and was wounded three times and suffered from shellshock, blackouts and terrible nightmares for the rest of his life. That’s Arnild pictured above, both as a young man and as Private Godfrey. In Torquay Town Centre in 1917 Arnold was handed a white feather by a tall young woman wearing a fox fur. This was the symbol of cowardice given to young men who weren’t in uniform – she didn’t realise that he had served with courage, and been stood down from duty.

He took it without comment. When he was asked why, he answered: “I wasn’t wearing my soldier’s discharge badge. I didn’t want to advertise the fact that I was a wounded soldier and I used to carry it in my pocket.”

Other residents can be unforgiving. Author and poet William Pryor is the great-great-grandson of Charles Darwin. He was also a heroin addict for 12 years in the 60s and 70s, and in 1972 William moved to Torquay and opened Cosmic Books in Market Street. His autobiography records how in 1973 he was “busted by local drugs squad as customer of local pushers of ‘Chinese’ (heroin)”. He turned Queen’s evidence against his suppliers and was assaulted by their friends “knocking four teeth from his head”.

Finally, we have a youthful Mick Jagger damning with faint praise. In August 1964 the Rolling Stones used the Grand Hotel as a touring base for five days. Mick told the Torquay Times that Torquay was “a great town. But I shouldn’t think there’s much to do in the winter”.

On the other hand, most visitors do have a great time in the Bay…