In September 1964 Sean O’Casey died of a heart attack in Torquay at the age of 84. He was cremated at the Golders’ Green Crematorium.

The dramatist, long an exile from his native Ireland, had lived in St Marychurch for many years. His obituary in the New York Times read: “From earliest days in the drab streets and two-story brick boxes of Dublin slums until his aging years of self-driven British exile amid the red earth and salt air of Torquay, this gaunt fiery writer never abandoned his faith in the dignity of man.”

The dramatist, long an exile from his native Ireland, had lived in St Marychurch for many years. His obituary in the New York Times read: “From earliest days in the drab streets and two-story brick boxes of Dublin slums until his aging years of self-driven British exile amid the red earth and salt air of Torquay, this gaunt fiery writer never abandoned his faith in the dignity of man.”

Sean O’Casey was born in Dublin in 1880 and he grew up surrounded by the tenements that would form the backdrop of his ground-breaking plays. He joined the Gaelic League in 1906 and learned to speak Irish. He also became a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and became involved in the Irish Transport and General Workers Union which represented the interests of the unskilled workers who lived in the Irish tenements.

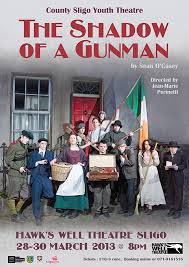

After early rejections, his first play, ‘The Shadow of the Gunman’, was produced by The Abbey Theatre in Dublin in 1923. It dealt with the impact of revolutionary politics on the normal people of Dublin. It was followed by ‘Juno and the Paycock’ (1924) and ‘The Plough and the Stars’ (1926) which dealt with the Civil War and the Easter Rising respectively. Some audiences greeted ‘The Plough and the Stars’ with derision as they misinterpreted it as an anti-nationalist rather than an anti-war play. In 1929, his play ‘The Silver Tassie’, was rejected and O’Casey was so disgusted he left Ireland to live in England for the rest of his life .

.

He wrote a further 15 plays. These, however, were less realist and more symbolic and expressionist. With the exception of ‘Within the Gates’, none of his later plays received either critical or commercial success. He also issued a six part autobiography known collectively as ‘Mirror in my House’.

Even in his 80s, “looking very much the poor country vicar with his worn tweed jacket, pipe, white hair, ascetic face and steel-rimmed glasses”, Sean continued to call out to young writers not to be “afraid of life’s full-throated shouting, afraid of its venom, suspicious of its gentleness, its valour, its pain and its rowdiness” .

.

The man whose plays had sparked riots and who had irritated both churchmen and atheists was now almost blind. He, nevertheless, continued to seek out “the restless vigour of the young and enjoyed the laughter and rows” of Torquay’s pubs and streets.

“The artist’s life,” he advised, “is to be where life is, active life, found in neither ivory tower nor concrete shelter; he must be out listening to everything, looking at everything, and thinking it all out afterward.”

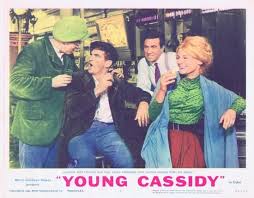

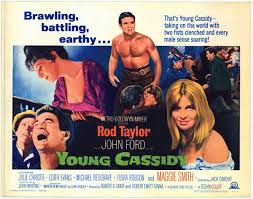

Despite his failing eyesight, Sean continued to write until his death. Many essays came from his his portable typewriter from his third-floor flat in Villa Rose in St Marychurch. Sean died while Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was filming ‘Young Cassidy’ (1965), a movie based on his autobiography. Here’s the trailer staring Rod Taylor:

The New York Times suggested that he wrote his own epitaph in the last of his autobiographical books which he wrote in the third person: “Here with w hitened hair, desires failing, strength ebbing out of him, with the sun gone down, and with only the serenity and calm warning of the evening star left to him, he drank to Life, to all it had been, to what it was, to what it would be. Hurrah!”

hitened hair, desires failing, strength ebbing out of him, with the sun gone down, and with only the serenity and calm warning of the evening star left to him, he drank to Life, to all it had been, to what it was, to what it would be. Hurrah!”

In 2012 a blue plaque commemorating Sean was unveiled at Villa Rose, Trumlands Road, St Marychurch. Sean’s daughter, Shivaugn, attended the event.