In February 1873 the Torquay novelist Annie Hall Cudlip visited a séance. She came to explore her interest in Spiritualism, a belief that the spirits of the dead have the ability to communicate with the living.

During the séance Annie saw “spirit faces” through a haze of smoke, one of which was apparently her dead mother. Her companion saw the face of, “a little girl, only her eyes and nose were visible, the rest of her head and face being enveloped in some white flimsy material like muslin… This was my dear lost child, who had left me as a little infant of ten days old.

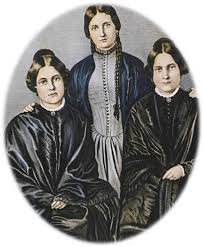

This particular séance took place at the peak of the spiritualist phenomenon. It was a time when contacting the dead was a mix of parlour game, public entertainment and religion. The Victorian Spiritualism craze began in 1848 when the Fox sisters in New York (pictured above) claimed that curious rapping sounds were messages from the spirits of the dead. These spirits could be asked questions and would answer by rapping. However, one of the sisters later confessed that she had made the noises by cracking her knee joints.

In 1852 table rapping came to England. In the fashionable health resort of Torquay, our élite quickly seized on the new sensation. We were ready for something that would reassure the public that there really was an afterlife. Indeed, organised religion was seen to be out of touch – in Ellacombe, for example, people were complaining that church sermons were long, dull and dry.

An exciting alternative was Spiritualism. It was also respectable – Queen Victoria practiced table rapping. Torquay harbourside resident, the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning (above) was fascinated. She enquired, “Do your American friends ever write to you about the rapping spirits?”

It’s worth noting how an interest in the occult was often associated with a commitment to progressive ideas, such as vegetarianism or the right to vote. The Suffragette Annie Kenney – who rallied her sisters in Torquay – became a committed spiritualist. Indeed, being a medium was one of the few professions where women were seen as being equal to men. These were the days when an unaccompanied woman walking on the Strand ran the risk of being accused of being a prostitute. Séances were expected to be entertaining and, in a society of strict rules, they offered a means for men and women to meet with the gas lights turned low.

Mediums, on the other hand, needed to compete for an audience. Accordingly, séances moved on from simple table rapping and came to feature a range of increasingly bizarre supernatural phenomena. These could include spirit writing, furniture floating in the air, possession by spirits, and accordions playing themselves. Incidentally, voluminous skirts were useful as a hiding place for the objects that would later materialise. This escalation would eventually lead – as in Annie Hall Cudlip’s séance – to the full materialisation of spirits. A ‘spirit’ would leave its cabinet and wander amongst the audience, perhaps trailing ‘ectoplasm’ – this was supposedly a supernatural vapour that sometimes solidified. Spirit photographs were also extremely popular. These were usually double exposures which purported to show the sitter with a ghost, and were a profitable sideline for local photographers.

Yet, Spiritualism could also be a haven for the eccentric. For example, in the 1880s a group calling itself the Order of the Temple occupied Cloudlands, a house in Chelston. Their leader, the spiritualist Countess Marie Borel, believed that her adopted son, Prince Baptiste St John Borel, had special powers. The Countess understood herself to be the “woman clothed with the sun” who was to “bear the child to rule the world with a rod of iron”.Yet, we hear nothing more of her or the Prince, so sadly the Messiah wasn’t to come from Chelston!

As it grew in popularity Spiritualism attracted inevitable criticism and scrutiny. It was noticed that sometimes the spirits seemed to have interests originating in this life rather than the next…

In 1867 the famous society medium DD Home visited Torquay. The same year Home (pictured above) was taken to court by a 75-year-old widow. The medium had contacted the elderly lady’s long-dead husband and had been told to pass on the message that his wife should adopt Home and shower him with gifts, including a sum of £30,000. She later changed her mind and demanded the money be returned. The resulting high-profile court case caused the aristocracy to be wary of taking the advice of mediums.

The claims of the spiritualists eventually attracted the attention of the scientific community and in 1882 the Society for Psychical Research was formed. The Society examined Spiritualism and exposed a range of tricks. Their investigators found that fraudulent mediums used confederates, hidden compartments, sleight of hand and even electrical devices. Posing as members of the public, they would ‘break the circle’, seize hold of ‘apparitions’ and find they were disguised mediums or their assistants. Consequently, many mediums gave up and left their profession, some emigrating to Australia.

Yet Spiritualism didn’t die out. Regardless of widespread evidence of fraud, belief in talkative spirits continued. It was particularly prevalent in times of mass grieving, such as after the First World War. One prominent spiritualist and Torquay visitor was the Sherlock Holmes author Conan Doyle (pictured above). He wrote ‘The History of Spiritualism’ in 1926, and was a member of the paranormal investigation organisation The Ghost Club. Proclaiming his belief in the afterlife, on August 5 1920 Conan Doyle gave a lecture entitled ‘Death and the Hereafter’ at Torquay Town Hall to a mainly female audience. The meeting was presided over by local builder and Freemason Henry Paul Rabbich, the then President of Paignton Spiritualist Society.

Another local claiming psychic powers was Violet Tweedale (above). Violet became involved in the Spiritualist off-shoot Theosophy, and was a member of the magical Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, one of the largest influences on twentieth century occultism. In 1917 Violet took part in the exorcism of a possessed medium during a visit to the reputedly haunted Warberries’ house Castel-a-Mare. The incident was documented in her memoirs ‘Ghosts I have Seen’ (1920).

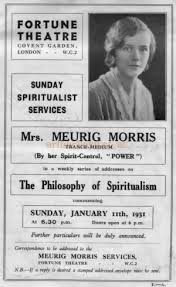

As a specialist on all things supernatural, Violet was called as an expert witness in a famous legal case when a medium sued for libel in 1932. This was Mrs Meurig Morris who had begun her long career contacting the dead at a séance in Newton Abbot in 1922. Reviewing a series of Meurig Morris services at a London Theatre, the Daily Mail wrote a review titled ‘Trance Medium Found Out.’ Meurig Morris sued for libel. After a long trial no allegations of fraud against Meurig Morris were proved. On the other hand, the Mail wasn’t liable for damages as the paper had published in the public interest. The jury had found it difficult to decide whether the medium was sincere, or if she was merely a fraud – a challenge that remains when looking at psychic claims.

Today Spiritualism retains a core of adherents, either as a faith system or as a form of entertainment – there’s a Spiritualist Church in Paignton, while ‘Spiritualist Mediums and Healers’ can often be seen in the Bay’s theatres.