For perhaps thirty years Torquay offered a welcome interruption between school and the kind of good life that most people expected they should one day live.

In the resort young people could experience a few months or years of freedom before the responsibilities and rewards of marriage, family, home ownership, and secure work, followed by a comfortable retirement. These ‘girls and boys interrupted’ would then return to their hometowns and resume the life that had been the right of working people for generations.

Then the dream faded.

For most of history people were born, lived and died within a few miles of their birthplace. Few working-class young people had the option to travel to other places for pleasure rather than necessity. During the latter years of the twentieth century these restrictions loosened.

For most of history people were born, lived and died within a few miles of their birthplace. Few working-class young people had the option to travel to other places for pleasure rather than necessity. During the latter years of the twentieth century these restrictions loosened.

An exception for young men wanting to broaden their horizons was to join, or be forcibly recruited by, the armed forces. Many consequently experienced foreign places during the Second World War. And when the conflict ended, around 160,000 eighteen-year-olds were annually called up for two years of National Service. The last conscripted soldiers left service in 1963.

Another opportunity, but only for the privileged and exceptional, was higher education. However, only 4% of school leavers went to university in the early 1960s, rising to around 14% by the end of the 1970s. Nowadays, more than 40% of young people start undergraduate degrees.

Another opportunity, but only for the privileged and exceptional, was higher education. However, only 4% of school leavers went to university in the early 1960s, rising to around 14% by the end of the 1970s. Nowadays, more than 40% of young people start undergraduate degrees.

Most young people in the post-war period, however, left education at the age of 15 or 16 and were able to access ample employment opportunities within their local areas. In the industrial parts of Britain this usually meant a job for life in the factories, mines, steel works and shipyards.

Women, on the other hand, had fewer options. A lesser number of women were in paid employment, and they were generally not expected to have careers, but to rather take on short-term jobs before marriage and children.

Life for many young people in post-war Britain could be bleak. The legacy of war was still to be seen in vacant bombsites, damaged houses, and temporary prefabs. Almost half the population lived in private rented accommodation, often in sub-standard rooms or bedsits. There were more than three children in the majority of families, a quarter of British homes had no electricity, and many did not have a telephone or an indoor toilet. Rationing only ended in 1954, nine years after the war ended.

Life for many young people in post-war Britain could be bleak. The legacy of war was still to be seen in vacant bombsites, damaged houses, and temporary prefabs. Almost half the population lived in private rented accommodation, often in sub-standard rooms or bedsits. There were more than three children in the majority of families, a quarter of British homes had no electricity, and many did not have a telephone or an indoor toilet. Rationing only ended in 1954, nine years after the war ended.

Yet there was very low unemployment. Between 1950 and 1973 joblessness averaged 2% and was always well under one million. There was a particular demand for flexible, though not especially skilled, labour, which brought a steady growth in young people’s earnings. There were also more young people around. A surge in the birth rate at the end of the Second World War increased the numbers of those aged under twenty from around three million in 1951 to just over four million by 1966.

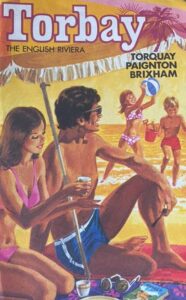

In summary, the youth population was rising, they had money to spend, some had experience of travel, they had rising expectations of a better life, and were often living in overcrowded homes. For those young people Torquay offered an alternative to a routine passage through life, a way to temporarily relocate to a place which needed low-skilled labour, and which could offer live-in accommodation.

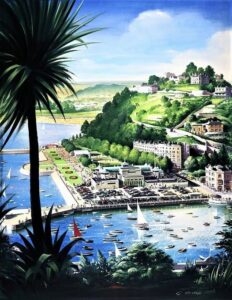

Moving to Torquay to find work was nothing new, of course. For a century the resort had attracted workers to service its villas, hotels, and service industries.

Moving to Torquay to find work was nothing new, of course. For a century the resort had attracted workers to service its villas, hotels, and service industries.

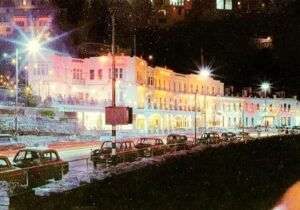

Torquay was seen as a glamorous and special place, frequented by the most affluent of vacationers. While about half the population spent a holiday by the sea, usually visiting a nearby resort such as Brighton or Blackpool, the Bay was a distant and comparatively expensive destination. It could take a full day to travel to South Devon and the resort prided itself as being for the more discerning. Working class tourists were gently redirected to nearby Paignton.

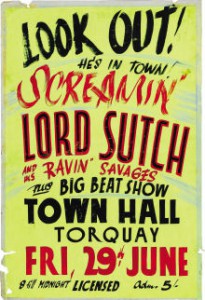

Here was a place to reinvent, live independently, find love, and make new friendships, away from parents and the constricting assumptions and standards of church, family, and home community. Although Torquay was a relatively small town, entertainment was plentiful in pubs, clubs, and the theatres. Popular entertainers of the day walked the streets while Lionel Digby brought in the famous bands.

Here was a place to reinvent, live independently, find love, and make new friendships, away from parents and the constricting assumptions and standards of church, family, and home community. Although Torquay was a relatively small town, entertainment was plentiful in pubs, clubs, and the theatres. Popular entertainers of the day walked the streets while Lionel Digby brought in the famous bands.

In 1951 Torquay’s population was 53,281; in 1961 it was 54,046. Not a great increase, though many of the peripatetic workers wouldn’t have shown up in the Census. Yet, we still see the presence of female service staff in the long-standing gender imbalance of 23,624 males to 30,422 females.

Another significant and long-standing component of the local workforce were those whose sexual behaviour deviated from the heterosexual norm. Torquay had always offered anonymity and an escape, though a low profile was still required for fear of legal prosecution or social persecution.

The post-war influx of young people further included those searching for a new meaning to their lives. Some were inspired by Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel ‘On the Road’ with Torquay becoming a kind of British San Francisco. Donovan rather than Dylan; Ruby Murray rather than Joan Baez.  Local writer and poet Mike Williams was there and has charted his generation’s Torquay sojourn. He remembers,

Local writer and poet Mike Williams was there and has charted his generation’s Torquay sojourn. He remembers,

“The beatnik lifestyle was mainly one of part-time work, the cheapest possible rented rooms, support from the National Assistance Board, and loafing about on beaches and in pubs. On the whole beatniks were tolerated in Torquay: this was because the need for cheap hotel labour was never satisfied; there were always jobs available.”

Undeniably, the work on offer was low-skilled, poorly paid, seasonal, and often demanded unsociable hours. But this was never a career, only a short-term paid holiday. And there was always a way back for those taking these working-class sabbaticals.

Undeniably, the work on offer was low-skilled, poorly paid, seasonal, and often demanded unsociable hours. But this was never a career, only a short-term paid holiday. And there was always a way back for those taking these working-class sabbaticals.

Promoting and idealising the alternative and exciting lifestyle at the seaside were a series of movies. While Britain had little to rival the American ‘teenpic’ industry, young people were targeted with films featuring pop stars such as Tommy Steele and Cliff Richard. Generally, these were lightweight movies, though an exception came in 1964 when the cream of young British acting talent came to Torbay to film ‘The System’.

Starring Oliver Reed, ‘The System’ is the story of a group of young men scouring Torquay’s seasonal holidaymakers in search of sexual conquests. The storyline was unusually provocative as it showed sex outside of marriage. In Britain public attitudes towards sex and marriage remained strongly conservative. Causing particular concern for the censors was the hint at an abortion, procedures that were illegal until the 1967 Act. You wouldn’t get that in a Cliff Richard movie. Indeed, in the United States where it was known as ‘The Girl Getters’, it was heavily cut for its adult content.  Notably, Paignton, rather than Torquay, was chosen to explain class divisions at the seaside. As noted, not all tourist resorts were the same and this appears to have been picked up by director Michael Winner. Exploring how working-class holidaymakers dressed, behaved, and spoke, we have the famous Oliver Reed’s mocking description of the nature of the Grockle.

Notably, Paignton, rather than Torquay, was chosen to explain class divisions at the seaside. As noted, not all tourist resorts were the same and this appears to have been picked up by director Michael Winner. Exploring how working-class holidaymakers dressed, behaved, and spoke, we have the famous Oliver Reed’s mocking description of the nature of the Grockle.

Here’s the whole movie:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XKqvubSH0fM

In 1979 another film was released suggesting that while some things had changed, much had stayed the same. Ominously, in the early 1970s unemployment passed one million, a rate of around 4%. The level rose to 1.5 million by 1978 and the rate to around 5.5%.

Notwithstanding disturbing trends, ‘That Summer’ starred a very youthful Ray Winstone and begins with two boys and two girls arriving in Torquay and easily finding work and live-in accommodation. The lads quickly come into conflict with a Scottish gang, reflecting the rivalries between groups from other parts of Britain, a theme that also features in ‘The System’.  ‘That Summer’ portrays Torquay in its finest days. Across the nation the great British seaside holiday was beginning to decline with the arrival of cheap package holidays to Spain where sunshine was almost guaranteed.

‘That Summer’ portrays Torquay in its finest days. Across the nation the great British seaside holiday was beginning to decline with the arrival of cheap package holidays to Spain where sunshine was almost guaranteed.

‘That Summer’ can be seen in its entirety at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r5iNpV-Vg4M

What was simultaneously taking place was that there were progressively fewer reasons for Torquay’s young workers to return to the cities and towns of their birth. Unemployment soared in the early 1980s, the official level exceeding 3 million by 1982 and the official rate reaching 11.9% in 1984. The loss of so many well-paid jobs was particularly hard felt in the industrial heartlands of Scotland, the Midlands, the north of England, and in South Wales. The ‘traditional’ youth labour market was subsequently dismantled in the 1980s and a raft of policy interventions redefined education, employment, and training. It also extended the age at which most young people transitioned into work and adulthood.

Over a short few years, jobs for life and good pensions were eroded, while proud working-class communities changed for ever. For many there was little to go back to.

Over a short few years, jobs for life and good pensions were eroded, while proud working-class communities changed for ever. For many there was little to go back to.

Today Torquay is a cosmopolitan town with the accents heard in the street from across the nation and, during the twenty-first century, the world. Amongst the tourists and day-trippers are those who came for a short working holiday and never left. Their interregnum in Britain’s premier resort had become a forever stay.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon