The 1911 music hall song ‘You can do a lot of things at the seaside that you can’t do in town’ describes the attractions of the resorts:

“Bashful little maidens, modest as can be,

Like to have a nice splash when they’re by the sea.

In their bathing dresses, pretty frills and bows,

You see more for for nothing than you see in penny shows.”

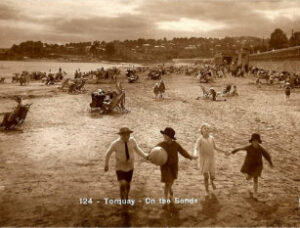

When the railways arrived in 1848 Torquay society was shocked. It was no longer insulated from working class visitors. Alongside the villas of the affluent came the boarding houses, while the streets filled with traders, street musicians, minstrel shows and itinerant photographers. Within a few years the beach and promenade became a riotous fairground.

Torquay largely escaped the Victorian day tripper – unlike Margate and Brighton, the Bay was a bit too far – but the staying tourist began to arrive in large numbers. Yet, with that liberation from the daily grind of work in the cities came another release. Working class folk brought their less sophisticated manners and a liking for alcohol with them.

There were attempts to repel the working class tourist. Sundays were made as unexciting as possible, while it was hoped that they might be redirected to the less expensive and more permissive Paignton. These efforts largely failed.

Eventually respectable folk would retreat from the promenade and the public assembly rooms to their own private clubs and drawing rooms. Then, realising times had changed, they would abandon Torquay in July and August, to return in the autumn and winter to a calmer town.

Torquay had rapidly transitioned from a sedate health resort to a place of leisure and pleasure. The sea was a liminal place, on the edge, a special and beautiful setting. Torquay presented itself as another time and space, brighter than reality. It had grand exotic architecture influenced by the Mediterranean and adorned with tropical plants.

Above all Torquay was somewhere different, where normal rules and restrictions need not apply. It was here you could reinvent yourself as someone more important. On the promenade and the beach social class could be disguised or pass unnoticed and for some the seaside acted as a marriage bureau. What happened in Torquay; stayed in Torquay…

You could even dress differently. The very clothes conscious Victorians developed a fashion appropriate for the seaside, nautical straw boaters and striped blazers while women let their hair hang loose in a way that would have been frowned upon at home. As boundaries were tested this could go too far. In 1853 Torquay’s Chief Constable Charles Kilby complained of the, “unbecoming manner that young women of the town wander around the thoroughfares without bonnets and shawls”. Note that many of these examples target the behaviour of women rather than men…

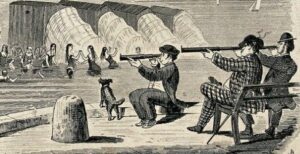

Sexuality could be more openly expressed by the sea, though there were often advances and then a reaction. Male nude bathing was acceptable up to 1860s, with many men not wanting the French style of mixed bathing. Nevertheless, the wearing of drawers or calecons would become obligatory, and later the full body swimming suit. To further promote morality came the bathing machine; though there were always those men who would use their telescopes to view the women bathing.

And it is no surprise that the postcard developed at the seaside, an early focus being images of young women on the beach.

A leisure-based society meant that Torquay was predominantly female. In 1871 there were already 12,772 resident females to 8,885 males. As there were few alternatives to employment as servants, and an ever-present demand, it was also a place of prostitution. Prostitutes could be found at night frequenting harbour pubs and Cary Green – the area in front of the Pavilion.

Again we see the local authorities attempting to clamp down on the most obvious forms of immorality. In January 1893 the landlord of the Marine Tavern, a one-storey pub situated in front of the Pavilion, was accused of assaulting a policeman and for being drunk and disorderly. However, the defence argued that he was sober and that he had only taken offence when a passing policeman had accused his wife of being “a woman of loose character”.

According to the landlord, he had been waiting at the Fish Quay for the arrival of the ferry, which brought in a good deal of custom, leaving his wife unaccompanied. A policeman had approached his wife and that’s where reports differ. The police said the landlord went berserk and had to be restrained by a number of officers both at the Harbourside and later in the police station; the landlord said that he was assaulted and badly beaten. Despite a number of witnesses saying that the landlord was of good character and had not been drinking, and accusations that Torquay’s police had a reputation for being heavy handed, the court accepted the testimony of the police and he was jailed and lost his living.

In 1899 the landlord of the Abbey Inn on Abbey Road was charged with allowing his pub to be used as “a habitual resort of women of ill-fame”.

A Detective Thomas watched the Abbey Inn on the night of March 12 between the hours of 8 and 11. “He saw women of loose character enter. They stayed for a considerable time – between 10 and 25 minutes. They entered and returned several times on the same evening, sometimes alone and sometimes in company with men… Entering the Inn, he saw three loose women in one of the rooms.”

As unaccompanied women of good character were unlikely to visit an inn, evidence of impropriety included a notice instructing females not to remain in the house for more than a quarter of an hour.

On one occasion the detective heard the landlord shout: “Time, Ladies!” indicating that women were not being escorted by a man. While being cross-examined, Detective Thomas said: “There is nothing to distinguish them from others except their bad language. The house was a quiet one and perhaps was not likely to attract women of the town in pursuit of their vocation.” The defendant protested on his arrest: “What can I do with so much rates and taxes to pay. They bring me my living.” Nevertheless, he was fined £5 with £1 costs and the brewery took away his tenancy.

Despite legislation and suppression Torquay’s prostitutes had no alternative to their trade and local young males were often warned of the dangers of the town. In early 1914 a ‘Big Meeting of Men’ was held in Torquay Town Hall by the YMCA. 800 men attended to hear a series of speakers. They heard that: “Hundreds of lads went under in the moral life every year either through ignorance or curiosity. Filthy picture postcards often led to a loose and unclean life. In Torquay there were thousands of girls and women decking themselves out in bright clothing and donning tawdry jewellery that they might walk the streets and try to attract so-called men and young men”.

And here’s that 1911 music hall song ‘You can do a lot of things at the seaside that you can’t do in town’ suggesting the delights of the seaside:

…

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us