In July 1847 there was an “extraordinary case” of sexual assault which “greatly excited” the town of Teignmouth.

In response to escalating concern the police undertook “a Spring-heeled Jack investigation” and searched for “a delinquent of this genus who occupied himself during the winter in frightening and annoying defenceless women, some of whom were rather roughly handled.”

In one incident in January a servant of a Miss Morgan, a lady living in Bitton Road, had been twice assaulted between nine and ten at night.

What aroused most interest, however, was that the man was heavily disguised. He wore a skin coat, “which had the appearance of a bullock’s hide”, along with a skull-cap and a mask with horns.

Eventually suspicion fell upon a Captain Finch of Shaldon, “a man of alleged ill health, and apparently sixty years of age, about the last person that could have been suspected”.

Eventually suspicion fell upon a Captain Finch of Shaldon, “a man of alleged ill health, and apparently sixty years of age, about the last person that could have been suspected”.

The Magistrates heard that the servant “belonged to the humblest rank, while Captain Finch had been considered highly respectable”. Nevertheless, though the Bench expressed pain at accusing an old soldier of such offences, Finch was found guilty and was fined 17 shillings for each attack. Social class seems to have been a factor here for this extraordinarily lenient sentence considering how many local folk were being hanged at the time for far lesser crimes.

The Magistrates heard that the servant “belonged to the humblest rank, while Captain Finch had been considered highly respectable”. Nevertheless, though the Bench expressed pain at accusing an old soldier of such offences, Finch was found guilty and was fined 17 shillings for each attack. Social class seems to have been a factor here for this extraordinarily lenient sentence considering how many local folk were being hanged at the time for far lesser crimes.

Why this caused national and international interest was that the attacks were initially, blamed on Spring-Heeled Jack, a notorious and vicious ghost prankster who terrified people throughout much of the nineteenth century.

Jack was a bogeyman, a means of scaring children into behaving by telling them that, if they were not good, Spring-Heeled Jack would get them.

By the time of the Teignmouth assaults, Spring-Heeled Jack had acquired notoriety during a decade of shocking appearances and attacks.

By the time of the Teignmouth assaults, Spring-Heeled Jack had acquired notoriety during a decade of shocking appearances and attacks.

The first of these came in October 1837 when a woman by the name of Mary Stevens was walking to Lavender Hill in London when a tall coated man leapt from a building into the street. He then grasped her with his metal claws, and while forcibly kissing her, began tearing at her clothes. After her screams were heard, the aggressor fled the scene, leaping back to the building he first came from.

Many other London sightings then followed and later that year Jack made it to Brighton where a gardener saw “a bear-like creature run along a wall topped with broken glass, which then jumped down and chased the frightened man before scaling the wall and escaping”.

Jack was described as having a terrifying appearance, clawed hands, and eyes that “resembled red balls of fire”. It was claimed that, beneath a black cloak, he wore a helmet and a tight-fitting white garment like an oilskin. He possessed a “Devil-like”aspect, was tall and thin, and had the appearance of a gentlemen.

Jack was described as having a terrifying appearance, clawed hands, and eyes that “resembled red balls of fire”. It was claimed that, beneath a black cloak, he wore a helmet and a tight-fitting white garment like an oilskin. He possessed a “Devil-like”aspect, was tall and thin, and had the appearance of a gentlemen.

Other reports describe his ability to breathe out blue and white flames and that he wore sharp metallic claws on his fingertips. Jack’s title, of course, came from the belief that he had springs on the heels of his boots.

Jack’s visits were then reported to be happening all over Britain and it was at this time that he made his first appearances in South Devon.

One place supposedly haunted by Jack was the coastal route that is now the A379 Teignmouth Road.

One place supposedly haunted by Jack was the coastal route that is now the A379 Teignmouth Road.

The historian Theo Brown remembers her father saying that during the nineteenth century nothing would induce anyone to walk from St Marychurch to Shaldon after dark. This road was said to be haunted by ‘Spring Hill Jack’ (sic). It was a place where “balls of fire would roll out of the hedges in front of people who ventured there at night”.

So why did Jack take residence in a quiet South Devon lane when he seemingly preferred leaping from city rooftops?

So why did Jack take residence in a quiet South Devon lane when he seemingly preferred leaping from city rooftops?

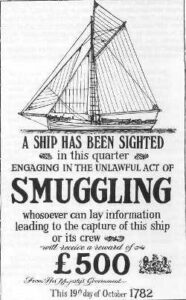

One suggestion is that his visits coincided with an increase in smuggling.

What had previously been simple small-scale evasion of duty had turned into a huge industry. The high rates of duty levied on tea, wine, spirits and other luxury goods made their import and the evasion of the duty a very profitable venture for our impoverished fishermen and seafarers. On the other hand, if the men were caught, they were hanged.

As with other supernatural manifestations in the area, was the Jack legend useful in explaining lights late at night, and a way of dissuading local folk from nocturnal excursions?

As with other supernatural manifestations in the area, was the Jack legend useful in explaining lights late at night, and a way of dissuading local folk from nocturnal excursions?

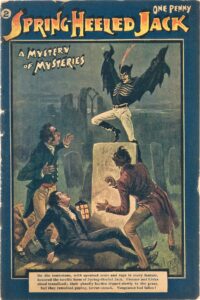

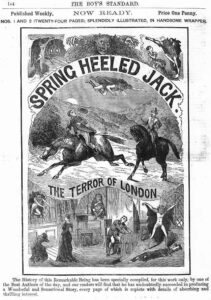

Even when smuggling declined, Jack’s notoriety continued. Between 1870 and 1890 he began to take on a more “devil like persona and look”, with people saying they had seen wings instead of an overcoat.

Witnesses also reported that he had either the face of a “demon or devil” or was wearing a mask. Due to the tales of his bizarre appearance and ability to make extraordinary leaps, the spectre started to appear in news articles, early novellas and ‘comics’.

Witnesses also reported that he had either the face of a “demon or devil” or was wearing a mask. Due to the tales of his bizarre appearance and ability to make extraordinary leaps, the spectre started to appear in news articles, early novellas and ‘comics’.

Though his impersonators such as Captain Finch were apprehended, Spring-Heeled Jack remained elusive, was never captured, and may still be out there somewhere.

Now Jack is largely forgotten, though he occasionally turns up in popular culture – such as in this song: