“If you wake at midnight to the sound of horses’ feet,

Don’t go drawin’ back the blinds nor lookin’ in the street.

Them that asks no questions, isn’t told a lie.

Now watch the wall my darling while the gentlemen go by”.

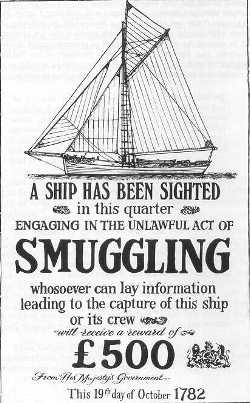

On May 13, 1783, there was a sea battle in Torbay; and a mass fight on Paignton’s beach.

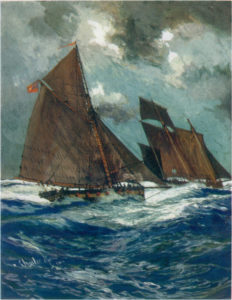

There were two vessels on each side. One side consisted of the Revenue Cutters ‘Spider’ and ‘Alarm’. Facing them were ‘The Swift’, with 16 guns and a crew of 50, and a sloop under the command of Thomas Perkinson of Brixham- these two ships were smuggling a huge consignment of illicit goods.

‘The Swift’, en route to Paignton, was spotted off Brixham by the Revenue men. Revenue man Captain Swaffin attempted to seize the smallest smugglers’ ship but was captured and held prisoner. There then followed an exchange of fire between ‘The ‘Swift’ and ‘The Alarm’. However, the Revenue ships were supported by the cannons from the garrison at Berry Head and the smugglers eventually retired.

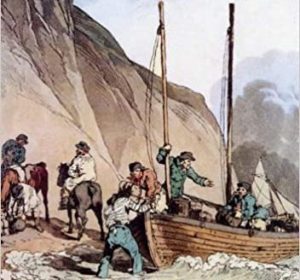

On shore a hundred local men were waiting for their consignment of 4 tons of tea and 9,000 gallons of spirits. During unloading, fighting on the beach ensued with John Stanton, a Cockington smuggler, attempting to kill a Revenue man called Thomas Petheridge, who “was knocked down by a rock and judged likely to lose an eye”. Two others of Captain Swaffin’s crew escaped, one by hiding under a boat, another by swimming away.

This was one incident in the long cat-and-mouse game between Torbay’s smugglers and those responsible for dealing with tax evasion.

Yet this was just the latest skirmish in a tradition Torbay folk had been following for a very long time. When John Leland visited in the sixteenth century he recorded, “thirty hoggesheads of wine in a sellar in Torbay and sugars in quantities not known”.

Indeed, it could be argued that the real mothers and fathers of Torbay were organised criminals, and not the Georgian gentlefolk we’re told about in parochial sophistries.

“Five and twenty ponies trotting through the dark,

Brandy for the parson and bacchy for the clerk,

Laces for the ladies and letters for the spie,

Now watch the wall my darling while the gentlemen go by”.

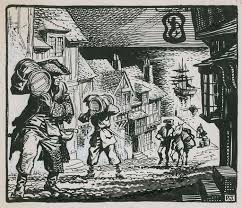

Smuggling was a massive business in the eighteenth century- a quarter of England’s overseas trade was illegal. Across England and Wales it was estimated that 60,000 of the most able men were directly involved in smuggling. But this wasn’t just a male preserve – 100,000 women and children worked as hawkers and distributors of contraband. That’s out of a population of around 7.5 million.

Devon and Cornwall were particularly active in the illicit trade and became more so when smuggling the southeast of England was suppressed. We certainly had natural advantages: our coast faced trade routes; we had secluded coves, beaches and caves; and a long tradition of shipbuilding and fishing. And it all fitted nicely with more acceptable pursuits – Brixham’s fishing fleet was known to bring home extras alongside their catch.

Smuggling is about making money and saving money, and a lot of money was at stake. A single cargo on a ship could be worth up to £10,000 – the equivalent to £1,800,000 today. Certainly the trade offered an escape from poverty, but it was also a way to resist an unjust society.

During the eighteenth century England was often at war with its continental neighbours, and later with the United States. Taxes were consequently high on luxury goods, such as tea, spirits, tobacco, fine fabrics, playing cards and fashionable clothes. And goods were even more expensive when taxes were increased in the years around 1740, in the early 1780s, and after 1815.

Smugglers called themselves free traders and could offer cheap goods, at half or two-thirds of the normal price. They could do this as those goods were substantially cheaper in Europe. Tea was 6 pence a pound in France, but cost 7 times that in England; tobacco costing £10 in the Netherlands could be sold at £100 at home; while French Cognac – known as Cousin Jackie – cost five times as much.

Smuggling was accordingly a highly profitable venture, but if the men were caught, they were hanged. And so the smuggling community of Torbay learned to evade detection and to defend itself.

By the 1780s it was said that half of the entire nation’s imported brandy was smuggled through Devon and Cornwall, alongside a quarter of all contraband tea. Sixty-three ships, a quarter of all smuggling vessels in England and Wales, were based in the two counties.

“Runnin’ through the woodlands you might chance to find

Little barrels roped and tied all full of brandywine,

Well don’t you shout to come and look nor use ’em for your play,

Just push the brushwood back again and they’ll be gone next day.”

Contraband was landed across the Bay. But sometimes it was better to avoid official observers stationed at Berry Head, so Anstey’s Cove and Oddicombe were preferred. We even have Brandy Cove, below Black Head, as a reminder of its past use (pictured below).

In Park Road, St Marychurch, there was a small house used by smugglers, where there was a hiding place under the hearth. Maidencombe Farm and Rocombe Farm also had places for concealing barrels of brandy. Between Barton Hall and Kerswell Cross there was an ancient hollow oak known as ‘The Brandy Bottle Tree’. This was used as a cache by smugglers landing kegs at Watcombe well into the nineteenth century.

“If you see the king’s men dressed in blue and red,

Well you be careful what you say and mindful what is said,

And if they call you pretty maid and chuck you ‘neath your chin,

Well don’t you tell where no one is, nor yet where no one’s been.”

Tasked with eliminating smuggling were teams of preventive officers. In 1780 four Revenue cutters operated between Dorset’s St Albans Head and Berry Head. There were also individual Customs officers at Torquay, Paignton, Brixham, Salcombe, Dartmouth and Totnes.

However, there were always insufficient officers to patrol our coastline and most smugglers were never caught.

Though less cruel than the violent gangs of Kent and Sussex, this was still a world of violence, lawlessness and intimidation. For example, a smuggler called Drake lived in a cottage at Petitor – he was also said to have had a sideline as a wrecker, deliberately decoying ships on the rocks for easy plundering.

Torbay was known for its large armed gangs, and those confederacies could often act without fear. In December 1760, for instance, thirty horses and twenty-five armed men arrived in Exeter. This was a gang that had brought in a consignment of tea from Torbay and they apparently made no attempt to disguise their profession. It was reported that, “the gang readily resorted to violence”.

And so there was, alongside community solidarity in our Bay, a great deal of fear of the smuggling gangs. Not surprisingly then, those smugglers that were caught were often not convicted. The Dartmouth Collector wrote, “We think that it is almost impossible to convict an offender by a Devonshire Jury who are composed of farmers and generally the greatest part of them either smugglers or always ready to assist them in securing and secreting their goods”.

It was always wise not to be a witness. Hence, Kipling’s instruction, “Now watch the wall my darling while the gentlemen go by”.

By the early years of the nineteenth century the Bay was changing and so was smuggling. The Revenue men had more and improved ships and were better organised on-shore. In response, the smugglers changed techniques and tactics… as they still do in modern Torbay.

Today, we have mostly forgotten Torbay’s criminal roots. But perhaps there remains a folk memory of their activities in the number and variety of old ghost stories we have. All our three towns have a legacy of tales of the supernatural. Were these designed to keep people from venturing out at night, and to explain away those strange lights and sounds on our beaches and in our sunken lanes?

Here’s Torquay visitor Rudyard Kipling’s Smugglers Song: