When we look at a picture of Victorian Torquay there’s one thing that we can’t really see. That’s what the town actually smelled like.

And it stank.

The smell would have hit you instantly- a mixture of animal dung, faeces, urine, body odour, coal and wood smoke. Our streets and rivers would, at times, have overflowed with a mix of rainwater, animal and human waste.

In 1841 Torquay had a population of 5,982. A decade later this was 11,474. By 1901 it reached 33,625, by absorbing St Marychurch and Cockington.

First of all, there was the ever present coal and wood smoke. Every home and business needed energy and had to burn something- the result could be soot and the smoke of hundreds of fires saturating the sky.

There would be horses everywhere drawing coaches and flatbed delivery carts. They were working all day and constantly hungry and thirsty. With few places to dispose of animal´s faeces, it was found all over the streets.

The River Fleet was effectively an open sewer and there were no public toilets. Urine soaked the streets – there was an experiment in London’s Piccadilly with wood paving but this was quickly abandoned because of the stench of ammonia.

Perhaps surprisingly household waste wasn’t a great problem. Refuse was valuable and as much waste as possible was recycled. Dust-yards were driven by the monetary value of household waste (or household ‘dust’) rather than any environmental legislation or public health concerns. Household dust comprised largely of coal ash from domestic fires which was in demand for brick making,

Today we take the availability of water for granted. But it was once a far less plentiful resource. During the early nineteenth century, Torquay derived its water from springs, wells and rainwater tanks, and from 1826 the Palk Water Works. Water was then collected at a reservoir at Ellacombe, fed by its own springs which supplied neighbouring houses. There was also a water tank at Torre, two in St Marychurch, two in Torwood and a spring on the Braddons. But this still restricted access for many.

Torquay was a deeply divided society. Visitors to the town had their guide books giving information on what places to visit… and what places to avoid. Other clues would be found in the town’s names. Clearly, Belgravia would be suitable for the wealthy visitor, while Pimlico would have associations with that other slum area in London.

When the Canadian visitor Isabella Cowen visited in 1892, she recorded, “I have seen more luxury since being in Torquay than in all my previous life.” This was a town claiming to be the richest in England where women in sumptuous flowing gowns and men in tailored suits carved a path through people dressed in rags. The rich lived in the villas on the hills while the often emaciated poor live in deep valleys.

And the smell could often inform you of your location – the affluent Warberries or working class Torre. Just how many buckets of water for drinking, washing, cooking, cleaning, and laundry could be carried up to a third-floor tenement in Pimlico, Swan Street or George Street?

Then came the challenge of increasing amounts of human waste. To cope with this every home had a cesspool. Ideally this was located in the back garden away from the house, but in more crowded areas it was in the basement.

Cesspools were built to be porous so the liquid part of the waste could seep away into the ground- and often into the nearby river Fleet. The residue of solid matter left was then removed by ‘night soil men.’ It was illegal to empty cesspools in the daytime because of the smell.

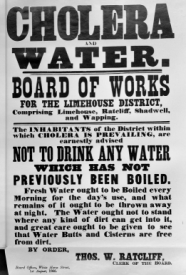

Several developments made local folk accept that change had to be made. The first was the realisation that poor sanitation caused disease.

In the 1860s, Louis Pasteur demonstrated the relationship between microorganisms and infectious disease, causing a huge shift in thinking about illness and sanitation. Foul smells were increasingly recognised as being more than just unpleasant.

In 1849 sixty six people died from cholera and dysentery over a period of six weeks in Torquay. Many of the dead were buried in Cholera Corner in the churchyard of the Greek Orthodox Church of St. Andrew off Lucius Street. As was to be expected, the cases occurred mainly in those oldest and poorest districts.

Torquay’s authorities had already begun to take action to tackle overcrowding and disease. Nevertheless, it took decades for people to accept that local government had a role in how they managed their household, their rubbish, and their toilet facilities.

One technological change that had an unforeseen consequence was the invention of the water closet. We’re familiar with the wall mounted cistern that became popular in the 1870s, but these new devices were initially connected to cesspools, not the new sewer system which was initially just for rainwater. The extra volume of flushing water overwhelmed the old cesspools and people started becoming concerned about the escalating stench coming into their houses and possibly bringing in diseases. This need to remove human waste from the household was one of the great driving forces of sanitary reform.

adopted the Public Health Act and the first meeting of the Local Board of Health took place in September 1850. Conditions then gradually began to improve. In 1865 the Local Board of Health made “a good wide street between the bottom of Union Street and the Strand.” This replaced the narrow and poorly constructed alleyways on both sides of the River Fleet. At the same time, the odoriferous Fleet was confined to a tunnel- and it’s still there.

Then there was body odour.

During the Middle Ages the Church condemned nakedness which resulted in an aversion to bathing that lasted for several hundred years. It was common to go for weeks without washing the body – although hands, feet and faces were still washed regularly.

What constituted proper hygiene for women was often debated, mostly by male doctors.

Once or twice a month, a Victorian woman could indulge in a lukewarm soak- hot and cold temperatures were believed to cause health problems or even insanity. During the weeks between baths, a woman would wash with a sponge soaked in cool water and vinegar. She rarely washed her hair and certainly not her expensive clothes- gowns were just too fragile. Only white linen or cotton undergarments were washed.

Those men and women with money covered any unpleasantness with perfume. It wasn’t until 1888 that we saw the invention of the first successful brand of commercial deodorant called ‘Mum’.

A perhaps surprising Torquay aroma would have been patchouli, associated today with hippie culture. Before export, dried patchouli leaves were tucked into the folds of Indian textiles to deter moths, impregnating them with that unmistakable, musky aroma. In Victorian Britain, Indian shawls were all the rage, so the ubiquitous scent soon became symbolic of luxury.

The availability of water increased with the construction of Chapel Hill reservoir in 1856 and a second reservoir in the Warberries in 1872. But water remained precious. In working class homes baths were shared by the entire family, with the eldest family member using the water first, each taking their turn until the youngest, who went last.

As better hygiene took hold, strong perfumes for both men and women were no longer essential to combat personal aromas, so the industry aligned itself more with fashion and with women.

The Public Health Act of 1848 began waste regulation, while a second act in 1875 put an end to scavenging. Households were then obliged to store their waste in ‘a movable receptacle’. And so the modern dustbin was born.

Motor cars replaced horses, and we adopted new cleaning devices like showers and toothbrushes. The upper classes were first to install elegant baths in their villas though, even after indoor plumbing became a necessity instead of a novelty, it still took some time before people thought of bathing as something to do every day.

And gradually, the stench and perfume of Torquay would change…

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us