Symbols illuminate ideas and allow us to go beyond what is seen. They do this by creating links to concepts and experiences. Simple images can then give out complex messages.

For thousands of years people have recognised the qualities of animals and have used them to represent a range of ideas. Animals acted as symbols of people or places, offering popular understandings of the hoped-for qualities of a community. In doing this, they could embody the spirit of a specific location, perhaps a nation or a town.

Taking this theme of animals as the spirit of a place, there are two birds that are intertwined in Torquay’s history.

Taking this theme of animals as the spirit of a place, there are two birds that are intertwined in Torquay’s history.

The first is the swan, a graceful white bird, the largest of the waterfowl, and a symbol of the ancient Cary dynasty.

The Cary family lived at Cockington Court, and later Torre Abbey, for almost 300 years. From 1662 they were major landowners in Devon, served as MPs, and were active at the royal court. The meaning of the name of Carey is ‘dweller at the castle’ and is thought to be derived from the Manor of Carrey near Lisieux in Normandy.

When families adopted crests, the components were designed to signify their positive characteristics, to send a message that other educated folk would be able to read and understand.

When families adopted crests, the components were designed to signify their positive characteristics, to send a message that other educated folk would be able to read and understand.

Beasts of land, sea, and air have always been part of heraldry. They function as picture writing, employed to distinguish individuals, armies, and institutions. These symbols, which originated as identification devices on flags and shields, were easy to recognise particularly when few people could read.

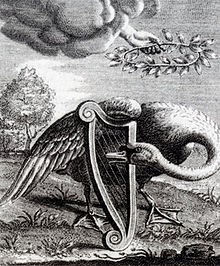

Accordingly, the Cary family crest is black, which proclaims constancy, on a white background which stands for peace and sincerity. It is further embossed with three roses for beauty and grace.

Accordingly, the Cary family crest is black, which proclaims constancy, on a white background which stands for peace and sincerity. It is further embossed with three roses for beauty and grace.

The motto ‘Sine Macula’ means ‘Without Blemish’. Illustrating this proud claim, atop the Cary crest is a white swan with its wings elevated and thrown back so as almost to touch each other.

The swan’s associations with human qualities come from its appearance and characteristics. These attributes have been recognised for a very long time. The swan was seen as a symbol of beauty in ancient Greece and was sacred to Apollo, the god of music. Though they are silent birds, it was believed that swans sang a beautiful song just before their death. ‘The swan song’ then became a phrase for a final gesture just before the end.

In Celtic mythology, the swan is seen to have links to the spirit world, able to shift between the earthly and supernatural realms. They feature heavily in European folklore and are present in many fairy tales. In some, an enchanted mortal is transformed into a swan; in others, the bird has the ability to shapeshift into human form at will.

In Celtic mythology, the swan is seen to have links to the spirit world, able to shift between the earthly and supernatural realms. They feature heavily in European folklore and are present in many fairy tales. In some, an enchanted mortal is transformed into a swan; in others, the bird has the ability to shapeshift into human form at will.

Swans mate for life and so have become a symbol of loyalty, while in film, literature, music, and dance, the bird is consistently used to suggest peace and tranquillity.

They are indeed a creature made for metaphors. A picture of elegance in motion but what is hidden from the eye is the frenetic activity beneath the surface. They make the sublime look effortless.

But don’t mess with a swan. They are powerful birds. Though mostly vegetarian, they ‘bite’, and their beating wings can break a human arm. So be wary when you see a swan lowering their neck, hissing, and rushing forward. They protect their territories from strangers and other swans, although they will tolerate ducks, smaller fowl, and even the ubiquitous seagull.

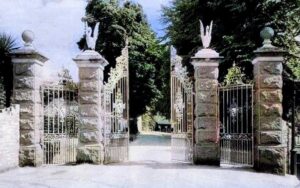

When the King’s Gardens ‘Model Boating Pool’ first opened on 19 April 1904 a pair of swans were donated by Councillor Mortimer. Their brethren reside there still, truculent guardians of the ponds. This gift recognised the old avian association on that Cary crest and swan statues can be seen topping the limestone gate piers at the entrance to the Abbey grounds. These gates were erected after the pond, which occupied the space for hundreds of years, was drained.

When the King’s Gardens ‘Model Boating Pool’ first opened on 19 April 1904 a pair of swans were donated by Councillor Mortimer. Their brethren reside there still, truculent guardians of the ponds. This gift recognised the old avian association on that Cary crest and swan statues can be seen topping the limestone gate piers at the entrance to the Abbey grounds. These gates were erected after the pond, which occupied the space for hundreds of years, was drained.

Our second emblematic bird of Torquay is, needless to say, the seagull.

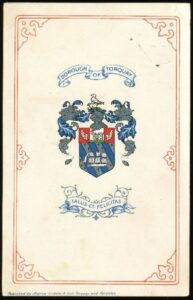

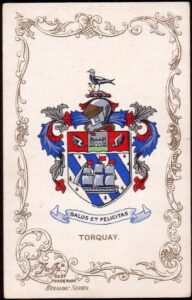

In 1892 Torquay was granted borough status by a Royal Charter, adopting the motto ‘Salus et Felicitas’ or ‘Health and Happiness’. On 29 May 1893 the resort was granted a coat-of-arms featuring a ship in full sail and a castellated gateway between two wings. The wings are derived from the arms of the Ridgeway family, Earls of Londonderry, who held the Manor of Tor Mohun, the nucleus of the community that would become Torquay. The gateway refers to that of Torre Abbey and the other emblems represent the town’s historic naval and maritime associations.

In 1892 Torquay was granted borough status by a Royal Charter, adopting the motto ‘Salus et Felicitas’ or ‘Health and Happiness’. On 29 May 1893 the resort was granted a coat-of-arms featuring a ship in full sail and a castellated gateway between two wings. The wings are derived from the arms of the Ridgeway family, Earls of Londonderry, who held the Manor of Tor Mohun, the nucleus of the community that would become Torquay. The gateway refers to that of Torre Abbey and the other emblems represent the town’s historic naval and maritime associations.

Crowning all this is a gull.

Seagulls live on every continent on the planet, even Antarctica. This has caused gulls to be present in just about every mythological tradition.

Seagulls live on every continent on the planet, even Antarctica. This has caused gulls to be present in just about every mythological tradition.

Sailors from medieval times avoided the gull’s gaze as the birds harboured a grudge and would peck out the eyes of any dead that had offended them. These days we have a more benign view of our omnipresent neighbours. Many Bay residents watch seagulls to predict the weather, some of us seeing gulls wheeling high in the sky and moving inland as a way to predict a storm approaching from offshore.

But they aren’t just volitant recyclers of the things we leave behind, a kind of aerial Womble to be seen cruising Fleet Street’s concrete canyon. Seagulls are conspicuous opportunists and that has made them a symbol of persistence, intelligence, and resourcefulness. These flying dinosaurs are the ultimate scavengers, evolution having crafted the perfect eating machine. They define the term omnivore, consuming whatever they can find.

But they aren’t just volitant recyclers of the things we leave behind, a kind of aerial Womble to be seen cruising Fleet Street’s concrete canyon. Seagulls are conspicuous opportunists and that has made them a symbol of persistence, intelligence, and resourcefulness. These flying dinosaurs are the ultimate scavengers, evolution having crafted the perfect eating machine. They define the term omnivore, consuming whatever they can find.

Their breeding and flocking habits further indicates a strong social connection, as well as the importance of togetherness and the importance of parenting.

We’ve taken them to our heart in Torquay United’s mascot of Gilbert the Gull, but don’t be fooled. They aren’t our Disneyfied feathered friends. We know that seagulls attack and eat pigeons and other birds, and even feed on each other. Many fledglings are snatched from their nests, and some are even gobbled down by their own parents. And if they were larger, or we were smaller, mere humans wouldn’t be able to leave our homes without becoming a Torbay takeaway.

We’ve taken them to our heart in Torquay United’s mascot of Gilbert the Gull, but don’t be fooled. They aren’t our Disneyfied feathered friends. We know that seagulls attack and eat pigeons and other birds, and even feed on each other. Many fledglings are snatched from their nests, and some are even gobbled down by their own parents. And if they were larger, or we were smaller, mere humans wouldn’t be able to leave our homes without becoming a Torbay takeaway.

Wariness of gulls goes back a long way. When the Old Testament book of Deuteronomy issued laws for the Jewish people, the seagull was identified as an unclean bird that should not be eaten:

Wariness of gulls goes back a long way. When the Old Testament book of Deuteronomy issued laws for the Jewish people, the seagull was identified as an unclean bird that should not be eaten:

“You may eat all clean birds. But these are the ones that you shall not eat: the eagle, the bearded vulture, the black vulture, the kite, the falcon of any kind; every raven of any kind; the ostrich, the nighthawk, the sea gull, the hawk of any kind…”.

It has been suggested that such birds were seen as ‘ambiguous’ creatures that didn’t seem to fall neatly into a category. The gull, not exhibiting the habits expected of other passive birds, was then ‘unclean’.

It has been suggested that such birds were seen as ‘ambiguous’ creatures that didn’t seem to fall neatly into a category. The gull, not exhibiting the habits expected of other passive birds, was then ‘unclean’.

We can therefore put forward two exemplars of Torquay.

One archetype is of the swan: ancient, pure, quiet, dependable, dignified, working beneath the surface.

The other is the seagull: modern, brash, raucous, both sinned against and sinful, quarrelsome, adaptable, and opportunistic.

These are then twin representations of Torquay, a feathered and figurative dialectic. Sometimes in conflict, periodically working together, taking long or short-term views of the resort, being able to live alongside each other but with clear but unwritten territories focussed on age, class, and gender.

These are then twin representations of Torquay, a feathered and figurative dialectic. Sometimes in conflict, periodically working together, taking long or short-term views of the resort, being able to live alongside each other but with clear but unwritten territories focussed on age, class, and gender.

Perhaps these birds do go some way to illustrate Torquay’s manifold identities. The town’s variations in behaviour and responses are in consequence evident at different times and places. Each self, having its own history,

Perhaps these birds do go some way to illustrate Torquay’s manifold identities. The town’s variations in behaviour and responses are in consequence evident at different times and places. Each self, having its own history,

idiosyncrasies, likes, dislikes, challenges and solutions. A Castle Circus and a Princess Pier Torquay; a Green Ginger and a Yacht Club Torquay; and a Saturday night and a Sunday morning Torquay.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon?fbclid=IwAR0i4IhQwcQkGwRXMdphbhzUyuHZ2N3w_ZbSWIpB3_F7ghYnbFHYQyOzcQk