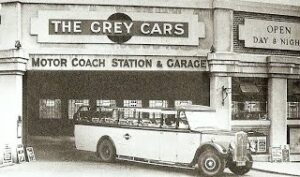

For a few years the motorised charabanc was a regular sight on Torquay’s streets with locals and tourists being transported by these ‘wagons with benches’.

Charabancs, a corruption of the French char à bancs – “carriage with wooden benches”- were originally horse-drawn. Following that original design, the motorised charabancs were long vehicles with an open carriage and five or more rows of seats; access was either from the rear or via doors along the side.

They were often multi-use vehicles. Daimler, Dennis and Leyland manufactured the basic chassis and then the body was built separately. This allowed a second body to be fitted in its place over the winter to keep the vehicle busy.

Others were just crudely converted lorries. In the summer of 1920 the Times described a typical charabanc: “The seats in such conveyance may be anything from deck chairs to wooden boxes. Generally they are overladen, and the more ambitious types carry a pair of domestic steps tied to the tailboard”.

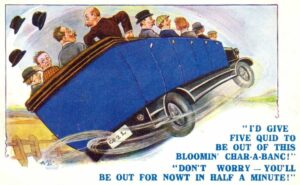

So charabancs were very basic transport – slow, noisy, uncomfortable, poorly upholstered with low-backed seats, and with little weather protection; possibly with a folding canvas hood though later models did have side screens and windows. They could also be dangerous as they had a high centre of gravity, particularly when overloaded. As the charabanc offered little or no protection to the passengers in the event of an overturning accident, fatal accidents were not uncommon.

In 1920, due to the increasing number of charabancs, their impact on other road users, along with concerns about the safety of passengers, emergency regulations and long-term legislation in Parliament were demanded.

Charabancs weren’t always welcomed in Torquay as they were particularly popular among working class people. This association between the working class and the charabanc had developed with the very concept of leisure time. Hiring a charabanc was an indulgence, and all that some workers could afford, but people could join together to pay for their hire.

Pubs were the natural centres for clubs and societies, and for the pick-up and drop-off of day-trippers and so charabancs came to be strongly associated with “joy-riders” on drunken outings. In 1872 we hear of Devon shop assistants celebrating the introduction of early closing on Thursday afternoons by taking a charabanc trip to Babbacombe. And, although Torquay avoided the mass of day-trippers seen in other resorts, they still brought parties of rowdy tourists to town in what were, in effect, mechanised pub-crawls. They also allowed folk to travel to nearby towns, villages and to further afield Dartmoor.

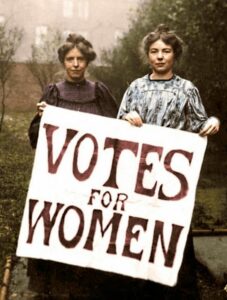

The charabanc had a role in the campaign for women’s suffrage. Torquay’s National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies lobbied politicians, collected petitions and held public meetings and in July 1913 Admiral Sir William Acland motored a Torquay contingent to Exeter to join a large demonstration. The town’s Society also organised missionary-like ‘pilgrimages’ to Totnes, Newton Abbot, Teignmouth and Dawlish.

One local who was very familiar with the charabanc was Agatha Christie. In the short story, ‘The Dead Harlequin’, from ‘The Mysterious Mr Quin’ series, the young artist Frank Bristow reacts angrily to the older Colonel Monkton’s snobbish attitude towards the tourist charabanc. They are also mentioned in the story ‘Double Sin’ when the motor coach Poirot is travelling in stops for lunch, “…in a big courtyard, about twenty char-a-bancs were parked – char-a-bancs which had come from all over the country”.

The charabancs weren’t around for very long. Towards the end of the 1920s they started to disappear as safer and far more comfortable motor buses took over Torquay’s roads.

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us