During the Seven Years War (1756-63) Admiral Hawke and the Western Squadron had just left Torbay when the French fleet made a sortie from the port of Brest. This led to the Battle of Quiberon Bay on 20 November 1759 – one incident in series of wars with France and her allies that lasted over 50 years and which developed into a global conflict.

The battle was the culmination of Britain’s efforts to eliminate French naval superiority, which could have given the French the ability to carry out their planned invasion. The 24 strong British force engaged a French fleet of 21 ships and, after hard fighting, the British sank or ran aground six French ships, captured one and scattered the rest. The battle established the Royal Navy as the world’s foremost naval power.

Among that British crew were a number of black sailors. Black people had been serving on board English vessels since at least the Tudor period. They worked as sailors, divers, soldiers, personal attendants and musicians and included free individuals, the press ganged and, before 1772, the enslaved.

During the eighteenth century black sailors were very common aboard British ships, and could be found among the crews of naval vessels, merchantmen, slavers and pirate ships. Accordingly, black mariners would have been a common site in Torbay.

Torbay was ideal as a large sheltered anchorage and was frequently used by the Channel Fleet – it was better protected from the prevailing wind than Cawsand near Plymouth. When in the Bay, the Royal Navy played the crucial role of defending Britain from invasion, protected Britain’s incoming and outgoing trade through the Channel and Western Approaches, and prevented the French fleet from setting forth on raids and expeditions.

All this activity needed to be supported and, in a reversal of our present day, Brixham was our largest town with a population of around 3,700. In contrast, Paignton had 1600 residents and Torquay only 800.

Brixham as a maritime town would have seen many black sailors in its streets. In 1800 half a dozen victualling craft from Plymouth would be stationed in the Bay while a naval hospital, a reservoir, pipe work and a watering jetty were built to service visiting ships. The town consequently also provided leisure opportunities for crew members. In so doing, it acquired an almost Wild West feel which necessitated the setting up of a marine guard to prevent, “scenes of drunkenness, obscenity, blasphemy and consequent casualties (by the men fighting with each other and falling over precipices) which, to the disgrace of His Majesty’s Navy obtained heretofore in watering the fleet at Brixham.” The town would therefore be amongst the most cosmopolitan in the country.

We only have limited information about the Royal Navy in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as contemporary records only show the country where recruits joined their ship, not their ethnicity. Also, black sailors almost always appear under their western ‘slave names’, rather than their African ones. On the other hand, a letter from Captain Martin of the Implacable to his brother in 1808 lists the origins of his crew – at least eleven of the hands were black, and possibly several more, compared with twenty-five shown as Welsh.

Black seamen were certainly recognised as being an integral part of the Royal Navy’s ascendancy to domination of the seas. Evidence of this can be seen at the base of Nelson’s Column which is decorated by four bronze reliefs which commemorate his victories. The one for the Battle of Trafalgar shows the admiral being carried from the quarterdeck of the Victory, moments after being shot by a French marksman. The scene has fourteen people in it, including Nelson, one of whom is clearly a black sailor (pictured above & below).

The Victory muster book listed 441 English on board on the morning of the battle. The remainder were: 64 Scots, 63 Irish, 18 Welsh, 3 Shetlanders, 2 Channel Islanders, one Manxman, 21 Americans, 7 Dutch, 6 Swedes, 4 Italians, 4 Maltese, 3 Norwegians, 3 Germans, 2 Swiss, 2 Portuguese, 2 Danes, 2 Indians, 1 Russian, 1 Brazilian, 1 African, 9 West Indians, and three French volunteers. Some of those gave their lives in the battle as the crew of the Victory suffered some of the worst casualties of the fleet, with 57 of her crew killed or dying of their wounds a few days later, with a further 102 wounded.

In 1815 the Bellerophon visited Torbay carrying the captured Napoleon (pictured above). That ship was also in action at the Battle of Trafalgar and had ten black crewmen on board. They included: Samuel Marlow, a 24-year-old Jamaican and former slave; Magnus Booth, 31, a West Indian ‘Mustee’ (of mixed race), his previous occupation being a writer suggesting he was educated; and Jon Hackett, 22, an African-American recruited in Maryland. One incident on the Bellerophon, describes how, “Franklin and a Marine sergeant were carrying down a black seaman to have his wounds dressed, when a ball from a rifleman entered his breast and killed him.”

Many black sailors were press-ganged as the Royal Navy was always short of sailors. Recruits, both voluntary and pressed, were sought not only at home but also in distant ports due to battle casualties, with desertion and disease constantly depleting the numbers of seamen. In particular, black water fever and malaria raged through the ships of the West Indian Division and necessitated the local recruitment of those best suited to cope with the conditions.

It is likely that the majority of black sailors in the Royal Navy were former slaves. In 1772 a landmark ruling in the case of Somerset vs. Stuart, stated that slavery did not exist in English Common Law. This meant that if a slave could escape from the sugar islands of the Caribbean to a place where English Law held sway such as a Royal Navy or British ship, they would become free. Gradually the British would oppose the slave trade more openly. Indeed, many naval officers, such as the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Barham, were prominent opponents of the practice. The slave trade in the British Empire was banned in acts in 1807 and 1811, and progressively stronger measures were put in place until 1833 when slavery itself was finally abolished.

Though there is little evidence of official discrimination, it was rare for a black mariner to be promoted beyond able seaman. They then had less access to pension benefits and were not promoted in the same numbers as working-class white seamen. Black mariners were largely kept out of royal dockyards, received less favourable compensation than whites and were often not considered for highly skilled work.

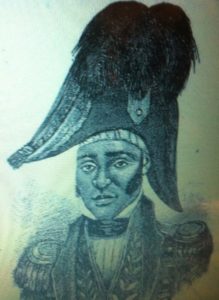

There were exceptions, however. John Perkins, known by the nickname Jack Punch, was probably a former slave in Jamaica. Jack (pictured above) joined the Royal Navy in 1775 and rapidly rose through the ranks to command the schooner Punch. In 1782 he was commissioned as a lieutenant, and by 1800 had risen to the position of post captain. He went on to command a number of ships, including the frigates Arab and Tartar. At the start of the slave revolt in Saint-Domingue he was captured and sentenced to death for supplying the rebel slave army with weapons, but escaped. During a remarkable career, he was said to have captured over three hundred enemy ships.

Some black sailors are only known to us because of their life after service. American-born, and almost certainly a slave, Billy Waters served in the Royal Navy for many years until he lost his leg in an accident aboard the Ganymede. After he was discharged he became a well-known street entertainer in London (pictured above). Along with Billy, black sailors appear in other contemporary cartoons, paintings, diaries, letters and photographs.

In 1815, when Napoleon’s wars were over and the swords turned into ploughshares, these men were no longer needed. The Royal Navy was reduced in size by 60% and Britain’s black sailors faced the same challenges as other seamen. Pressed men were released from service; some sought work as unskilled labourers or went into service; while others replaced those released pressed men. Those left disabled or sick from their years at sea would most likely have been reduced to begging.