In 1897 Annie Cann visited Torquay and wrote in her diary,

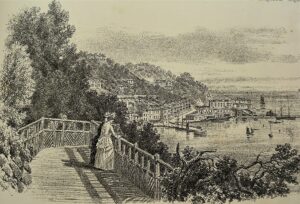

“We walked along the promenade to the town. We found it very clean, very white, very fashionable, and very hot. White walks, white dresses, blazing sun, no breeze, and no shade. Everyone wore gloves and carries a parasol… It is a place of ease, luxury, riches, convenience and prettiness – it cannot be called beautiful – for it is too artificial and unromantic to stir a pulse.”

By the time of Annie’s visit Torquay was claiming to be the richest town in England. It was the recreation epicentre of the largest empire in history which held sway over 412 million people, 23 per cent of the world’s population. Torquay was where the rulers and decision-makers of the British Empire, its dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and territories, chose for their vacations and retirement.

By the time of Annie’s visit Torquay was claiming to be the richest town in England. It was the recreation epicentre of the largest empire in history which held sway over 412 million people, 23 per cent of the world’s population. Torquay was where the rulers and decision-makers of the British Empire, its dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and territories, chose for their vacations and retirement.

Torquay was created to be an idealised miniature version of the imperial dream; an illusion constructed on certainties of power and privilege. But to fulfil that role the resort was always a mirage, becoming an impersonation of other places. It instinctively and reflexively transformed itself chameleon-like to satisfy of its target clientele and, at times, even to manufacture their desires.

Torquay was created to be an idealised miniature version of the imperial dream; an illusion constructed on certainties of power and privilege. But to fulfil that role the resort was always a mirage, becoming an impersonation of other places. It instinctively and reflexively transformed itself chameleon-like to satisfy of its target clientele and, at times, even to manufacture their desires.

Torquay looked like the coast of southern Europe because it was selected, designed and promoted to replicate the attractions of the Rivieras of Italy and France, those places denied to our Channel-hopping Grand Tour aristocracy by Napoleon’s imperial ambitions.

At least that was the myth. What actually gave birth to Torquay was death.

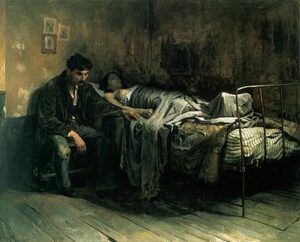

It was the decision to cater for the needs of the sick and dying, specifically for the relief and management of Consumption, a general term for lung diseases, mostly tuberculosis.

It was the decision to cater for the needs of the sick and dying, specifically for the relief and management of Consumption, a general term for lung diseases, mostly tuberculosis.

‘The Guide to the Watering Places of South Devon’ (1817) identifies that the town “was built to accommodate invalids”; while Octavian Blewitt’s ‘Panorama of Torquay’ (1832) confirms that “houses were erected for the accommodation of the invalids”.

They came to the health resort to recover. But many didn’t and never returned to their northern homes, as we see if we stroll around Torre’s churchyard.

They came to the health resort to recover. But many didn’t and never returned to their northern homes, as we see if we stroll around Torre’s churchyard.

Gradually the population increased. From 838 in 1801 to 5,982 in 1841. By that date the illness industry was well entrenched with Dr AB Granville writing, “The Frying Pan along the Strand is filled with respirator-bearing people who look like muzzled ghosts, and ugly enough to frighten the younger people to death”.

Consumption was ‘the romantic disease’ associated with such visiting poets and artists as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Robert Louis Stevenson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Charles Kingsley. The tragedy was that, in consequence, Consumption was not perceived negatively. The ailing generated an all-year-round income for businesses and provided employment for locals.

Consumption was ‘the romantic disease’ associated with such visiting poets and artists as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Robert Louis Stevenson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Charles Kingsley. The tragedy was that, in consequence, Consumption was not perceived negatively. The ailing generated an all-year-round income for businesses and provided employment for locals.

But we didn’t know that TB was infectious and so Torquay became “the south west asylum for diseased lungs” with the hotels “filled with spitting pots and echoing to the sounds of cavernous coughs, outside the only sound to be heard was the frequent tolling of the funeral bell”.

In another reinvention for the paying visitor, the Christian God’s antechamber mutated overnight with the opening of, what is now, Torre Railway Station on 18 December 1848; the more coastal Torquay Station following on 2 August 1859. The arrival of the railway to this isolated and peripheral part of the coast immediately exposed the town to wider public attention.  By 1851 the population was 11,474 and the heights around the old harbour had been transformed. In 1868 novelist and poet Mary Ann Evans, better known by her pen name of George Eliot, visited and wrote:

By 1851 the population was 11,474 and the heights around the old harbour had been transformed. In 1868 novelist and poet Mary Ann Evans, better known by her pen name of George Eliot, visited and wrote:

“I don’t know whether you have ever seen Torquay. It is pretty, but not comparable to Ilfracombe; and like all other easily accessible sea-places, it is sadly spoiled by wealth and fashion, which leaves no secluded walks, and tattoo all the hills with ugly patterns of roads and villa gardens. This place is becoming a little London, or London suburb. Everywhere houses and streets are being built, and Babbicombe will soon be joined to Torquay.”

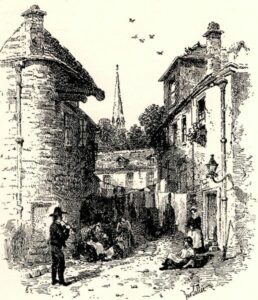

The railways opened a new experience for the British. Initially the beneficiaries were middle-class families seeking to escape from the crowds and pollution of the cities. But when lower middle- and working-class tourists began to arrive in ever greater numbers, they brought their morality, identity, less sophisticated manners and a liking for alcohol with them. This was a culture shock as many of these new sightseers were not the kind of folk that the town judged appropriate.

Adjacent to the villas of the affluent came the boarding houses, while the streets attracted traders, street musicians, minstrel shows and itinerant street artists. Within a few years the beach and promenade began to take on the characteristics of a disorderly fairground as Torquay transitioned to a place of leisure and pleasure for a mass clientele.

Victorian Britain had 48 places recognised as seaside resorts, but not all were the same. Torquay, along with a select few others such as Eastbourne, Bexhill and Frinton, wanted to preserve the image of being a premier resort. We emphatically did not want to respond to popular preferences and emulate the likes of Southend, Margate or Brighton.

Concerned at the direction of travel, steps taken to protect the resort’s identity. Fortunately, Torquay did have a significant advantage in not having major centres of industry in close proximity. Hence it largely escaped the transforming hordes of Victorian day trippers and was duly more able to target the more affluent visitor.

To attract this clientele Torquay offered comfort, the ‘right tone’ and specific entertainments reflecting the nature of the intended audience. At the same time, efforts were made to repel and divert the working-class tourist. Having seen the future of tourism, we knew who we wanted and who we didn’t want.

To attract this clientele Torquay offered comfort, the ‘right tone’ and specific entertainments reflecting the nature of the intended audience. At the same time, efforts were made to repel and divert the working-class tourist. Having seen the future of tourism, we knew who we wanted and who we didn’t want.

Sundays were made as unexciting as possible while it was hoped that the less-desired visitor might be redirected to the more affordable Paignton. It was thus implied that looser standards of behaviour would be allowed in other resorts. It was widely believed, for example, that risqué postcards prohibited in Torquay were acceptable for sale in neighbouring towns.

Princess ‘Pier’. Not a pier but a harbour wall. A true pier has water running beneath it

And, of course, that great symbol of the working-class Victorian resort, the pier, would be shunned by Torquay. Teignmouth and Paignton could have their piers, rowdy visitors and their noisy children, penny arcades, Punch and Judy shows, minstrels, acrobats, music hall smut, and ‘What the Butler saw’ machines. Torquay would much prefer the mature, refined, and affluent.

The nation was scoured for the best ways to meet the need for high-class tourist beds and to satisfy the appetite for sophisticated leisure; for theatregoing, bathing, yachting, and promenading. Following the Torquay tradition of mimicking faraway places, the town’s fabric took on exotic styles to replicate the allure of the Mediterranean, importing tropical plants to frame Italianate buildings in order to suggest romantic images of warmer climes, further promoting the idea of an English Riviera.

The nation was scoured for the best ways to meet the need for high-class tourist beds and to satisfy the appetite for sophisticated leisure; for theatregoing, bathing, yachting, and promenading. Following the Torquay tradition of mimicking faraway places, the town’s fabric took on exotic styles to replicate the allure of the Mediterranean, importing tropical plants to frame Italianate buildings in order to suggest romantic images of warmer climes, further promoting the idea of an English Riviera.

But while the tourism industry gave the town its distinctiveness, at the same time it fostered a social and political settlement that acted to discourage other forms of economic activity. Torquay’s working class was consequently atypical in that it was largely concentrated in the service and servile industries, low paid and difficult to organise.

The demand for staff to work in the many hotels drew in large numbers of workers. There were also over 18 per cent of Torquay’s population employed as household servants. Many staff lived with their employer to attend to their every need in a life of menial work, long hours, meagre pay, and often harsh treatment.

A majority of those in service were female, largely due to there being a tax on indoor male servants making men’s wages considerably higher, and that women were regarded as being more obedient. This saw a gender disparity in the town that would persist for over a century. In 1871 there were 12,772 females to 8,885 males in Torquay; by 1881 there was a population of 19,293 females but 13,665 males.

A majority of those in service were female, largely due to there being a tax on indoor male servants making men’s wages considerably higher, and that women were regarded as being more obedient. This saw a gender disparity in the town that would persist for over a century. In 1871 there were 12,772 females to 8,885 males in Torquay; by 1881 there was a population of 19,293 females but 13,665 males.

Hence power and influence remained in the hands of the few. And in the place of true self-empowerment of working people, there would arise a culture of altruism and paternalism; but always beneath the surface was the threat of overt domination and exploitation.

Torquay always saw itself as a resort above and apart, more a concept than a real place. it consequently evolved a self-image that became readily recognised and often critiqued by visitors.

Rudyard Kipling was one who recognised that pretention, “Torquay is such a place as I do desire to upset it by dancing through it with nothing on but my spectacles. Villas, clipped hedges and shaven lawns, fat old ladies with respirators and obese landaus (a kind of carriage).”

Rudyard Kipling was one who recognised that pretention, “Torquay is such a place as I do desire to upset it by dancing through it with nothing on but my spectacles. Villas, clipped hedges and shaven lawns, fat old ladies with respirators and obese landaus (a kind of carriage).”

While surface change was necessary to cater for new expectations, one constant remained. This was the imperative to maintain the town’s select position in the holiday hierarchy. There was always the anxiety that Torquay could become ‘Brightonised’ into just another seaside resort. In 1923 The Western Times was warning that, “Torquay is not Brighton, neither is it Blackpool. It stands upon a different plane to these watering places. A higher one”.

Nothing about this mission was subtle. In 1932 ‘The English Riviera Official Guide’ described the kind of visitor the town didn’t want. It condemned:

“Vulgarians whose idea of holiday is compounded of Big Wheels, paper caps, donkeys and n*****s (minstrels), tin whistles, and generally a remorseless harlequinade…. “

The Guide went on to describe the ideal tourist. They were “the thoroughly normal, healthy and educated people who are the backbone of the nation, love Torquay as few other towns are loved, and it is they who throng its pleasant ways the whole year round”.

Back in 1861 Charles Dickens described Torquay as “humbug”. He saw the resort as a fraud, relying on unjustified publicity and spectacle. The town was, he wrote, a “place I consider to be an imposter, a delusion and a snare”.

Back in 1861 Charles Dickens described Torquay as “humbug”. He saw the resort as a fraud, relying on unjustified publicity and spectacle. The town was, he wrote, a “place I consider to be an imposter, a delusion and a snare”.

Was he correct then? And if he came back now, would he come to a very similar conclusion?

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon