By 1870 there were 48 places classified as seaside resorts in a halo around Britain; but not all were the same. Torquay, along with Eastbourne, Bexhill and Frinton, wanted to preserve the image of a premier resort; it did not want to emulate the likes of Southend, Margate or Brighton.

By the opening of Torre Railway Station on 18 December 1848 – with the more coastal Torquay Station following on 2 August 1859 – Torquay had largely relinquished its image of being a substitute health spa and become a holiday resort. Yet it was still select with few being able to afford the time or money to travel by coach or steam ship to Devon’s south coast.

And so the town remained little more than a few clusters of villas built on hillsides in order to attract the upper classes.

The arrival of the railway to this isolated and peripheral part of the coast immediately exposed the town to public notice. Conversely, those seaside resorts missing out on hosting a railway suffered in contrast; neighbouring communities over time being assimilated to become suburbs of Torquay.

The railways opened up a new experience for the British. The main beneficiaries initially were middle-class families, though the less affluent were soon to follow. While Torquay largely escaped the Victorian day tripper, being a bit too far from the major cities, the staying tourist began to arrive in large numbers. This was a culture shock and brought major social change as many of these new visitors were not the kind of folk that the town judged appropriate.

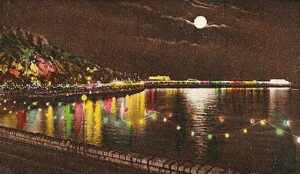

Working class tourists with their spending power, brought their morality, identity, less sophisticated manners and a liking for alcohol with them. Alongside the villas of the affluent came the boarding houses, while the streets attracted traders, street musicians, minstrel shows and itinerant photographers. Within a few years the beach and promenade took on the characteristics of a disorderly fairground as Torquay transitioned to a place of leisure and pleasure.

The danger was that those visitors and residents most valued by the town would either seek other resorts or travel abroad, an existential threat that could never be tolerated.

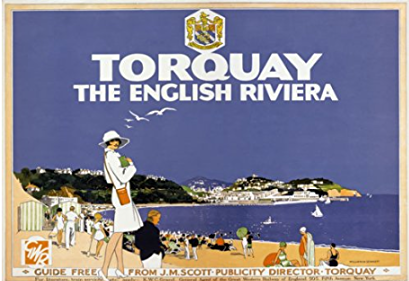

The town had a significant advantage in not having major centres of industry in close proximity, and so it was able to target the more affluent visitor. To attract this clientele, Torquay offered comfort, the ‘right tone’ and specific entertainments reflecting the nature of the intended audience.

It also made efforts to repel and divert the working class tourist. Sundays were made as unexciting as possible, contributing to the six-month long ‘Torquay War’ when the Salvation Army challenged the ruling.

Meanwhile it was hoped that the less-desired visitor might be redirected to the more affordable, and seemingly more permissive, Paignton. It was implied that lower standards of behaviour would be permitted in other resorts, it being widely believed, for example, that saucy postcards prohibited in Torquay were acceptable for sale in neighbouring towns. It fell to the Improvement Commissioners and their successors, the Local Board of Health, to regulate and control behaviour. Taking on positions of responsibility these upper middle class representatives were supported by a professional police force.

The town’s elite self-image was displayed in its architecture, in new styles but also in the decision not to undertake the forms of emblematic building seen in other Victorian resorts. The most conspicuous example is the absence of a true pier, the usual focus of a tourist resort.

Nevertheless, respectable folk did retreat from the promenade and the public assembly rooms to their own private clubs and drawing rooms. They would later abandon Torquay in July and August altogether, returning in the autumn and winter to a calmer town.

Segregation of tourists was further made possible by the practice of some British towns and cities with large factories having set holiday periods, wakes weeks, when the workforce would all decamp at the same time.

Torquay was, and would remain, a resort above and apart, more a concept than a real place. It consequently evolved a conservative and reactionary culture and identity that became recognised and often critiqued by visitors.

Charles Dickens disliked Torquay’s genteel and leisured society’s affectation of superiority which he referred to as “humbug”. The town was a “place I consider to be an imposter, a delusion and a snare”.

Rudyard Kipling was similarly critical, “Torquay is such a place as I do desire to upset it by dancing through it with nothing on but my spectacles. Villas, clipped hedges and shaven lawns, fat old ladies with respirators and obese landaus.”

Other visitors similarly remarked on the town’s pretensions. In 1897 Annie Cann recorded in her diary,

“We walked along the promenade to the town. We found it very clean, very white, very fashionable, and very hot. White walks, white dresses, blazing sun, no breeze, and no shade. Everyone wore gloves and carries a parasol… It is a place of ease, luxury, riches, convenience and prettiness – it cannot be called beautiful – for it is too artificial and unromantic to stir a pulse.”