On August 5, 1920, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave a lecture at Torquay Town Hall.

Here was a literary celebrity who had created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ‘A Study in Scarlet’, the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Holmes and Dr Watson. A prolific writer, Conan Doyle also wrote fantasy and science fiction stories about Professor Challenger, as well as plays, romances, poetry, non-fiction, and historical novels.

But the author wasn’t in Torquay to relate his literary achievements. He was here to deliver a lecture entitled ‘Death and the Hereafter’. In the Town Hall Sir Arthur would proclaim his firm belief that an unearthly world existed, and that Spiritualism could facilitate contact with the departed.

The meeting was presided over by local builder and Freemason Henry Paul Rabbich, the then President of Paignton Spiritualist Society and Vice-President of the Southern Counties Union of Spiritualists. During this visit, Sir Arthur stayed with Henry (pictured above) at ‘The Kraal’, 5 Headland Grove, Preston.

The newspapers remarked how the appreciate audience was mainly female. But not all locals were so welcoming. Sir Arthur later recalled that the Town Hall “was next to a church, and just as I started to speak the church bells began ringing, and I had to shout all the time.” This attempted sabotage seems to have come from the Anglicans of St Mary Magdalene’s.

In February 1923 Conan Doyle was back. This time it was to give a lecture at the Pavilion entitled ‘The New Revelation’, “the culmination of his many years of research as a Spiritualist”, presided over by Torquay’s Mayor GH Tredale. He stayed at the Victoria Hotel in Belgrave Road on this visit.

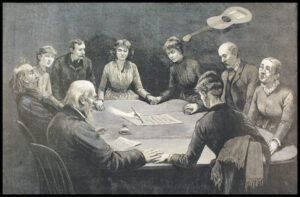

Conan Doyle’s unconventional esoteric interests had begun in the early 1880s. In his mid-twenties he experimented with mesmerism and telepathy while still a struggling young doctor in Southsea. He had grown up as a Roman Catholic but lost faith in traditional Christianity and in 1886 found an alternative in Spiritualism, becoming a member of the paranormal investigation organisation ‘The Ghost Club’.

In October 1917 he began to make speeches promoting Spiritualism. The movement had started in the aftermath of the American Civil War and there was no surprise that there was an upsurge in interest during and after the slaughter of the First World War. During the conflict Conan Doyle lost eleven family members either in combat or to disease, his eldest son and only brother among them. The war intensified his interest in life after death and he became one of the leading voices of the spiritualist movement in the post-War period.

“For the betterment of human life” he wrote works such as ‘The Land of Mists’ and ‘The History of Spiritualism’, both 1926. Hence the lectures and his central message of life going on after death. This crusade met with a broadly sympathetic response among the many people around the world who had similarly suffered bereavement.

Sir Arthur toured the globe speaking about what he saw as the “truth” of séances, mediums, and visitations from the dead. During the late Victorian and Edwardian eras Torquay had acquired a reputation as a centre for such occult practices and so the town was a natural stage for a Conan Doyle lecture.

Many, however, ridiculed Conan Doyle’s faith in Spiritualism. Sceptics shook their heads as the great man was tricked by fake mediums but still professed belief in the afterlife, psychic channelling, spirit photos, and ancient Egyptian curses. His readers were confused and couldn’t reconcile the rationalism and intelligence of Sherlock Holmes with his creator’s belief in the paranormal.

Sir Arthur just seemed to want to believe. He appeared to care little for public opinion and was very aware that his reputation, career and relationships were suffering; his friendship with Harry Houdini, the famous escapologist, ended because of their disagreements about Spiritualism.

Conan Doyle’s reputation wasn’t enhanced when, in 1917, two young cousins in Yorkshire took a series of five photographs of supposed fairies. Known as the Cottingley Fairies, he used these images to illustrate an article he had been commissioned to write for the Christmas 1920 edition of ‘The Strand’ magazine. The front-page banner headline was ‘Fairies Photographed: An Epoch-Making Event Described by A. Conan Doyle’. Sir Arthur interpreted the images as clear evidence of psychic phenomena and of a “primitive” life form. It was only in the 1980s that the cousins admitted that the photographs were faked, using cardboard cut-outs copied from a popular children’s book; though one cousin maintained that the fifth and final photograph was genuine.

Sir Arthur’s belief in the afterlife continued to the end… and even beyond.

A few days after his death in 1930, a Spiritualist meeting was held at the Royal Albert Hall. Ten thousand people were there with hundreds more trying to access the building. Arranged on the stage was a row of chairs for the family, including Lady Conan Doyle and several of the Conan Doyle children. One chair was left empty for Sir Arthur himself. This was so that he could make one final appearance and address his audience from ‘Summerland’, his name for “the undiscovered country”. Such a manifestation from beyond the grave would finally prove his critics wrong and solve the greatest mystery of all. Sadly, Sir Arthur did not appear. However, there were many people in the audience who claimed they had felt his presence amongst them.