This is about Torquay’s role in the world’s most famous kidnapping and an extortionate ransom demand.

It all began with England’s King Richard – known as the Lionheart. Even though Richard lived most of his adult life in Aquitaine and spent very little time – possibly as little as six months – in England, Richard the Lionheart is now perceived as the quintessential English king.

He was the Christian commander during the Third Crusade, and achieved considerable victories against his Muslim counterpart, Saladin, although he didn’t actually retake Jerusalem.

He was the Christian commander during the Third Crusade, and achieved considerable victories against his Muslim counterpart, Saladin, although he didn’t actually retake Jerusalem.

It’s on Richard’s long returning trek from the Third Crusade that our story begins.

Richard’s ship was wrecked in Italy, forcing him into a dangerous land journey across central Europe.

Shortly before Christmas 1192 the King was captured near Vienna by Leopold of Austria, who accused Richard of arranging the murder of his cousin. Moreover, Richard had offended Leopold by casting down his standard from the walls of Acre.

Shortly before Christmas 1192 the King was captured near Vienna by Leopold of Austria, who accused Richard of arranging the murder of his cousin. Moreover, Richard had offended Leopold by casting down his standard from the walls of Acre.

The detention of a crusader was, however, contrary to public law, and so the Pope excommunicated the Duke.

On 28 March 1193 Richard was handed over to the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI, who had already fallen out with the Plantagenets. In response, the Pope excommunicated Henry as well.

Nevertheless, Henry needed money to raise an army and assert his rights over southern Italy, and so he demanded a ransom of 150,000 marks (100,000 pounds of silver) before he would release the King.

That was 2 or 3 times the annual income for the English Crown. Eleanor, Richard’s mother, attempted to raise the ransom while both clergy and laymen were taxed for a quarter of the value of their property. The gold and silver treasures of English churches were confiscated, and money was further raised from other taxes.

That was 2 or 3 times the annual income for the English Crown. Eleanor, Richard’s mother, attempted to raise the ransom while both clergy and laymen were taxed for a quarter of the value of their property. The gold and silver treasures of English churches were confiscated, and money was further raised from other taxes.

Even though 100,000 marks was handed over, it still wasn’t enough. Nenerthless, on 4 February 1194 Richard was released.

This is where we come in.

As a guarantee that the remainder of the ransom would be paid, 67 high-born hostages were handed over. This additional 50,000 marks would never be paid, but the hostages were finally released in April, and the excommunications were lifted.

The local link is through William Brewer, major landholder, administrator and judge in England during the reigns of Richard I, his brother King John, and John’s son Henry III.

By 1179 William had been appointed Sherriff of Devon and, under Richard, was one of the justiciars appointed to administer the kingdom while the King was on his Crusade. He wasn’t popular, however. At times the men of Cornwall, Somerset, and Dorset would pay money to the King for his removal.

We know William was present at Worms, Germany, in 1193 to aid in the negotiations for the ransom of Richard. And, while not named, it has always been assumed that William’s young son, William Brewer the Younger, was one of those 67 hostages left with the Emperor.

We know William was present at Worms, Germany, in 1193 to aid in the negotiations for the ransom of Richard. And, while not named, it has always been assumed that William’s young son, William Brewer the Younger, was one of those 67 hostages left with the Emperor.

Every noble family had an interest in a monastic house and nearly a thousand religious houses were founded in England and Wales during the medieval period. Many were founded in conflict or in times of national or personal strife.

William founded and endowed three monasteries: Mottisfort Abbey in Hampshire; Dunkeswell; and, of course, Torre Abbey. Torre Abbey’s foundation Charter says it was built to pray for William’s own soul, for those of his predecessors and successors, and for the souls of Henry II and Richard.

William founded and endowed three monasteries: Mottisfort Abbey in Hampshire; Dunkeswell; and, of course, Torre Abbey. Torre Abbey’s foundation Charter says it was built to pray for William’s own soul, for those of his predecessors and successors, and for the souls of Henry II and Richard.

Accordingly, it’s believed that William Brewer founded Torre Abbey partly to give thanks for the return of his hostage son.

In 1196 six Premonstratensian canons from Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire founded the Abbey when William, lord of the manor of Torre, gave them the land.

In 1196 six Premonstratensian canons from Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire founded the Abbey when William, lord of the manor of Torre, gave them the land.

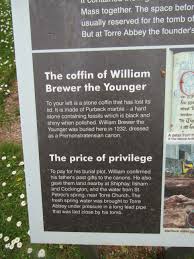

The other piece of evidence we have is that, when William Brewer the Younger died in 1233, he was buried in front of Torre Abbey’s high alter. And his grave is still there.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon