This is about Tuscan Torquay; and why we decided to build mock Italian church bell towers across our town.

In 1862 Charles Dickens wrote, “Torquay is a pretty place… a mixture of Hastings and Tunbridge Wells and little bits of the hills about Naples”. Ruskin would carry on the theme and call Torquay, “The Italy of England”. And what architectural style could then be more appropriate for the rapidly growing town than one that replicated the buildings and gardens of the Mediterranean.

And what architectural style could then be more appropriate for the rapidly growing town than one that replicated the buildings and gardens of the Mediterranean.

This was the Italianate, most popular between 1840 and 1885. It was a phase in the history of Classical architecture, yet another backward look, and part of the quest to provide buildings that evoked a romantic part of the world and which came from another time. The Italianate expressed the desire for greater freedom of expression; it looked to the more organic, and even complicated, and was intended to complement natural settings rather than overwhelm them.

The Italianate expressed the desire for greater freedom of expression; it looked to the more organic, and even complicated, and was intended to complement natural settings rather than overwhelm them.

This was a British interpretation of the architectural and natural splendours of Florence and the Italian countryside; effectively three-dimensional postcards of those European tours so favoured by Britain’s elite. The Italianate style was first developed in Britain in about 1802 by John Nash, with the construction of a Shropshire country house ‘Cronkhill’, and was further developed and popularised by the architect Sir Charles Barry in the 1830s.

The Italianate style was first developed in Britain in about 1802 by John Nash, with the construction of a Shropshire country house ‘Cronkhill’, and was further developed and popularised by the architect Sir Charles Barry in the 1830s.

It was initially intended as a suitable design for substantial homes or country estates and so was first introduced to Torquay in sites of two or three acres on the southern slopes of the Warberries and the Lincombes.  The earliest example of the Italianate in the resort is ‘Vomero’ in Stitchill Road , built in 1838, with its impressive portico; though, shortly after, ‘Wellswood Hall’ was built in the Warberries in 1840.

The earliest example of the Italianate in the resort is ‘Vomero’ in Stitchill Road , built in 1838, with its impressive portico; though, shortly after, ‘Wellswood Hall’ was built in the Warberries in 1840.

Its real popularity came when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert chose the Italianate for their new private home Osborne House in 1851. It subsequently became a popular design choice for the small mansions built by Britain’s new and wealthy industrialists; as the Italianate took its cues from the Renaissance, it appealed to Victorian intellectuals and the aspiring middle classes. The buildings reflected the image the English had of an Italian villa with its low pitched roof and overhanging eaves supported by large brackets. These would be further ornamented with porticos, columns and pediments. One of the most notable features was the campanile, imitations of the square church bell towers seen in Italy. Hence, Vane Tower on the skyline above the harbour side ; while the town centre has the clock tower of the Old Town Hall of 1852.

The buildings reflected the image the English had of an Italian villa with its low pitched roof and overhanging eaves supported by large brackets. These would be further ornamented with porticos, columns and pediments. One of the most notable features was the campanile, imitations of the square church bell towers seen in Italy. Hence, Vane Tower on the skyline above the harbour side ; while the town centre has the clock tower of the Old Town Hall of 1852.

Made popular across the nation by published pattern books, the style was soon imitated by architects and builders who applied it to homes of all sizes. It also had real practical attractions. Based on the humble Tuscan country farmhouse, its simple lines gave an irregular shape which could cater to a range of building materials, income levels, and available space.

The rise of mass-production meant that fashionable architectural details could be easily and affordably produced and applied. Meanwhile, technical developments such as iron-framed construction, plate glass, terracotta, polished local limestone and granite became commercially available for the first time. The style was easily adapted and could encompass spacious homes on sprawling properties for Torquay’s wealthy, while also fitting into much smaller urban plots. As it offered flexible floor plans, it became not just popular for residences but for institutional and commercial buildings. It was particularly suitable for hotels which could be altered without being demolished and rebuilt. The Imperial Hotel is a good example. Built in 1866 the original Italianate design was easily enlarged when the Jubilee Wing was added in the 1870s.

The style was easily adapted and could encompass spacious homes on sprawling properties for Torquay’s wealthy, while also fitting into much smaller urban plots. As it offered flexible floor plans, it became not just popular for residences but for institutional and commercial buildings. It was particularly suitable for hotels which could be altered without being demolished and rebuilt. The Imperial Hotel is a good example. Built in 1866 the original Italianate design was easily enlarged when the Jubilee Wing was added in the 1870s. Internally, the Italianate could be very impressive. Rooms could feature columns, painted panels, wall carvings, decorated ceilings and vaulted rooms, while lavish furnishings added to reflect the imagined opulence of ancient Mediterranean homes.

Internally, the Italianate could be very impressive. Rooms could feature columns, painted panels, wall carvings, decorated ceilings and vaulted rooms, while lavish furnishings added to reflect the imagined opulence of ancient Mediterranean homes. A further feature of the Italianate that so suited Torquay was the garden; often needing to be designed on steep slopes. Clever landscaping could transform a small space into something quite impressive. In homage to the Tuscan countryside, both house and surroundings were supposed to look natural, lush, and spontaneous.

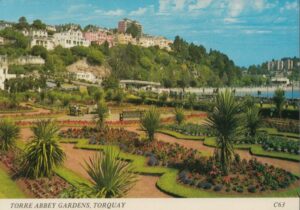

A further feature of the Italianate that so suited Torquay was the garden; often needing to be designed on steep slopes. Clever landscaping could transform a small space into something quite impressive. In homage to the Tuscan countryside, both house and surroundings were supposed to look natural, lush, and spontaneous.  Accordingly, the designs featured terraces, flights of steps, statuary, fountains, ponds and balustrades adorned with urns. The resort had the further advantage in being able to grow exotic plants to accentuate that Mediterranean ambience.

Accordingly, the designs featured terraces, flights of steps, statuary, fountains, ponds and balustrades adorned with urns. The resort had the further advantage in being able to grow exotic plants to accentuate that Mediterranean ambience.

The Italianate then spread beyond the private residence. Today, we see this evolution of the way in which our Victorian ancestors envisioned their world in Torquay’s parks and gardens.