Sybil Fawlty really ran Fawlty Towers.

She was a far more effective manager than her husband, handled crises calmly, and she knew that the hotel was there to generate an income, rather than to attract a better class of guest.

Sybil intimidated Basil who described her to O’Reilly, the builder, as having the ability to “kill a man at ten paces with one blow of her tongue.”

This is the stereotype of the seaside landlady. A resilient and tough businesswoman with an ineffectual man somewhere in the background.

Intriguingly, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some commentators were referring to ‘men’s towns’ – which had a masculine presence in industry such as mining or steel working. They also referred, often dismissively, to places where women had a social and political power base.

Following this impression, seaside resorts were often known as women’s towns. In 1871 there were 12,772 females to 8,885 males in Torquay, women far outnumbering men, as one of the principal sources of employment was domestic service.

Of course, much work in female employment was exploitative and poorly paid. Yet, there were a few roles that women dominated that gave them an almost equal place in society. These included the pub landlady and the guest house owner.

Torquay had a large number of both in a town of landladies, a community which gave women a powerful and influential position in an untypical town. This reinforced the liminal nature of the seaside resorts where class and gender were confused and inverted.

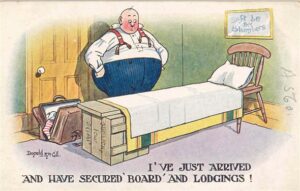

The role of guest house landlady had evolved with the town. In 1850 there were only 150 hotel rooms available in Torquay, with a further 70 lodging housekeepers offering another 350 rooms. From the 1860s onward, to cater for this new demand, there was a rapid growth in hotel building for the well-off, and they advertised themselves with prestigious titles: The Imperial; The Grand; The Royal.

But beyond the large hotels, lodging was in private houses. These were independently-owned and catered for the market by providing cheap, unpretentious accommodation.

Torquay was ideal for the growth of the trade as generously sized Victorian and Edwardian houses could easily be converted into boarding houses and small hotels. Then, during the twentieth century, the two World Wars left large homes without heirs. This made property prices relatively affordable for entrepreneurial buyers.

These guest houses – which would evolve into bed and breakfasts – had family members often working a 12-hour day. The guest house offered economic autonomy and domestic power to their owners, though we shouldn’t forget there was often the exploitation of domestic servants.

Notably, very few single men ran a guest-house, the sector being clearly perceived as being a woman’s business. If a married couple ran the house, the wife’s name was often above the door, the husband being relegated to a behind-the-scenes role. For older women and widows, taking in guests was one of the few income-generators available.

This may be because relatively few families depended on the trade exclusively. This was a seasonal and highly competitive industry and there was only a limited amount of money to be made. The males in the household usually had other occupations and we often see husbands appearing in the trade directories as lodging-house keepers in some years but not in others, suggesting that the guest house profession was a fall-back when other work wasn’t available.

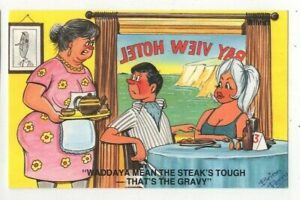

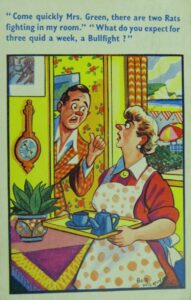

As profit margins were tight, the home limited in space, and the family workforce often stretched, many landladies found it necessary to impose a strict discipline. They offered few amenities and cut corners whenever possible. This imperative led to the idea of the landlady as being fierce, cunning, intimidating and, in caricature, often physically large; in contrast to their emasculated and downtrodden husbands.

As with many stereotypes, there was some truth here, but also the male-female role reversal and the existence of a cadre of powerful women does seem to have caused genuine unease. The landlady consequently ended up as a great British comic institution, the focus of jokes and seaside postcards for decades.

As for the reality, we have many reports, cartoons and songs, about how some lodgings were certainly run-down and dirty. Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray wrote of how poor seaside accommodation was: the people were dreadful; the landladies dishonest; and the food appalling. There were often inflated prices and hidden costs.

Canadian Isabella Cowen and her sister visited Torquay in 1892 and recorded in her diary that she first found furnished apartments at 38 Abbey Road. They weren’t impressed and called their apartment a “queer dark place”. Soon after they moved to 6 Torwood Terrace on Babbacombe Road where they found “the society of refined and intelligent neighbours”. However, having informed their landlady at Abbey Road that they were leaving, they believed that she took offence and retaliated by interfering with the sisters’ mail.

In March 1893 the children’s author Beatrix Potter visited Torquay. She found her accommodation unsatisfactory:

“I sniffed my bedroom on arrival, and for a few hours felt a certain grim satisfaction where my forebodings were maintained, but it is possible to have too much Natural History in a bed. I did not undress after the first night, but I was obliged to lie on it because there were only two chairs and one of them was broken.”

The landlady was a feature of the Torquay holiday and social landscape for a century but times changed.

By the seventies the golden age of the Torquay landlady was coming to an end. Redundancy payments and early retirement had attracted into the industry more male guest house owners and hoteliers. British holiday makers had found that they could travel to Mediterranean resorts with relative ease and at low cost. There were less tourists and the average length of stay was becoming shorter. Meanwhile, there were new forms of competition in caravans and self-catering while the larger hotels were offering lower rates to coach parties.

Landladies found that visitors’ expectations were rising and they had to offer more than basic accommodation – amenities such as television lounges and licensed bars – without raising prices too far. Perhaps the greatest challenge was in the provision of en suite bathrooms. Those old Torquay villas often proved difficult to modernise without losing too much capacity.

At the same time there were new fire regulations, VAT and capital gains tax.

Even though the landladies adapted and switched to bed and breakfast from full board, gradually the boarding house market shrank. The influence and power of this seaside small business model declined as the ownership of tourist accommodation moved from the local to the national, and now to the international.

And so, Torquay’s two new large hotels – the Premier Inn and the Hampton – are owned respectively by a national company, Whitbread, while Hilton has its base in Memphis, Tennessee.