Oh! I do like to be beside the seaside!

I do like to be beside the sea!

I do like to stroll along the Prom, Prom, Prom!

Where the brass bands play, “Tiddely-om-pom-pom!”

John Glover-Kinde (1907)

Visitors to the church yard of Torquay’s St. Andrew’s Church (originally St. Saviour’s) may well notice how many inhumations are not of local people but of visitors who saw out their last days in the town. This was the church which served Torquay in its days as a premier health resort and those who didn’t regain their health remain with us, a situation which persisted until 1895 when the churchyard at Torre was closed to burials.

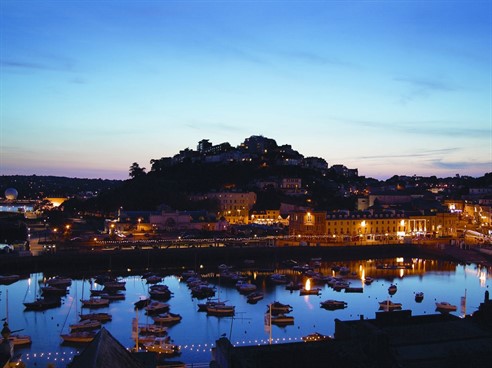

Under the guise of health benefits, the affluent had been visiting seaside resorts since the mid-18th century. Torquay, however, remained the insignificant collection of villages it had always been, in 1800 a small community of around 800 people. This changed during the Napoleonic Wars when the Bay was utilised as a sheltered anchorage by the Channel Fleet. Napoleon’s domination of the continent also denied the British aristocracy their European Tours, which benefitted the Bay which stood in as a substitute English Riviera.

For those who could afford to travel, Torquay’s mild climate attracted visitors to recover from illness or surgery with convalescent homes offering patients access to the benefits of “healthful” air, calm, rest, light, food and exercise. Significantly, the medical profession recommended health resorts depending on their relationship to a particular illness. A lung condition would be aided by, for example, the bracing Welsh mountain air while tropical diseases were the speciality of a warmer resort such as Torquay. Hence the presence in town of officers from the East India Company in the early nineteenth century, along with their Indian servants, making Torquay one of the few places in nineteenth century Europe where you could see Muslims and Hindus in their traditional dress.

Torquay changed profoundly with the opening of Torre Railway Station on 18 December 1848 – the more coastal Torquay station following on 2 August 1859. This improved transport connection resulted in rapid growth at the expense of those nearby towns not on Brunel’s railway. The population increased – to 11,474 in 1851 – as did our affluence. If we want to identify a time when Torquay decided on its future, it would be the day when we chose not to drive the railway to the habourside – as was originally proposed – but to locate it on the edge of town. This decision, to be a tourist town and not an industrial port, is still core to our self-image, economy, and many of the opportunities and challenges Torquay faces today.

Railways were a symbol of ruthless progress, overcoming anything that opposed them – public opposition, family land, the natural environment. And the arrival of the railway to this isolated peripheral coastal town immediately exposed Torquay to public notice – we were to become the most popular resort in the south-west. The trains brought major social change as they made access cheaper in time and money. Conversely, those resorts missing out suffered in contrast. Neighbouring communities would eventually become suburbs of Torquay and assimilated as the population quadrupled between 1841 and 1901 and further when the town was granted Borough status in 1872.

By the latter years of the nineteenth century Torquay was claiming to be the richest town in England. This lead to significant investment in infrastructure such as street lighting, public parks, road building and trams. Building styles were transformed with architecture taking on a more exotic style while tropical plants were used to suggest romantic images of warmer climes, again promoting the idea of an English Riviera.

The larger Victorian resorts, especially those which catered for the rapidly-expanding working-class holiday market, offered ‘pleasure palaces’. But outside of Blackpool, large-scale commercial entertainment seldom paid satisfactory dividends. Along with the great Victorian seaside hotels, they were particularly vulnerable to changes in popular taste and the economics of the industry. The original Torquay Winter Gardens of 1881, for example, was a cast iron and glass conservatory, able to seat up to 1,000 people for concerts. It failed, as did Torquay’s Opera House which still stands on the Strand.

.

But when you’re just the common or garden Smith or Jones or Brown

at business up in town, you’re got to settle down.

You save your money all the year ’til summer comes around.

Then away you go to a place you know, where the cockle shells are found.

The railways opened up a new experience for the British, the main beneficiaries initially being middle-class families seeking to escape from the crowds and pollution of the cities to the clean air and health benefits of the Bay. The seaside then became a place where a different culture evolved and it came to play a unique role in the lives of the Victorian people.

The Victorians popularised many of the classic seaside staples we still have today. These adopted traditions included, donkey rides, the afternoon promenade, candyfloss, Punch and Judy, buckets and spades, sandcastles bandstands, street photographers, military parades, piers, the music hall, gardens and exhibitions. In defiance of conventional table manners, eating fish and chips, cockles and whelks out of the bag while on the move became a classless seaside icon.

So just let me be beside the seaside!

I’ll be beside myself with glee

and there’s lots of girls beside,

I should like to be beside, beside the seaside,

beside the sea!

This focus on the needs of the paying visitor assured the dominance of an informal coalition of interest between Torquay Council, the tourism industry and the Church of England and created a (small c) conservative, and (big C) Conservative culture for a century or more. It would also give us the unwelcome title of ‘Torybay’. A local version of the ‘trickle-down theory’ of economics consequently took hold – where the interests of the tourism industry would be promoted at all costs, while alternatives would be ignored or suppressed.

Inevitably, there would be challenges to this conservatism. From the mid-nineteenth arenas of conflict developed when Torquay’s Establishment strove to preserve its self identified uniqueness: in public order; morality; and religion.

Torquay wasn’t immune to the uprisings of the Victorian era and experienced riots in the town in 1847 and 1867. However, these were unfocussed rebellions and quickly put down by the military. Due to the dominance of low wage and seasonal tourism as an employer the town didn’t develop an industrial working class with its own self confidence, organisations and political representation. And so those seen as troublemakers remained isolated, defenceless and unemployable. Even as late as the early 1970s the Police would encourage landlords from renting to undesirables.

Some of those that presumably would have entered local council politics became committed to the Bohemian lifestyle or diverted their energies into single issue campaigns – vegetarianism, Irish Home Rule, women’s suffrage- or became interested in Spiritualism and the Occult, leaving Torquay with an ongoing undercurrent of alternative belief systems.

Yet those escaping to the seaside would unavoidably bring with it the conflicts about morality and identity which were so pervasive in Victorian life. Torquay’s role as a ‘liminal’ place was enhanced. It was a gateway between land and sea, culture and nature, constraint and hedonism. Visitors with clashing values and expectations found themselves in close proximity – with some expecting relaxation and an escape from the pressures of life, others to compete in the promenade, to flirt, display and consume.

This large-scale expansion of Torquay as a resort exacerbated social and cultural conflict, particularly when the market for holidays broadened to include significant numbers of working class people. At first there were clerks and shopkeepers, then industrial workers. Working-class visitors relied on cheap excursions, organised by Sunday Schools, employers, temperance societies or commercial promoters. But rowdy young bachelors in mundane employment reinventing themselves for a fortnight posed a particular challenge to public order. It was no accident that the naughty postcard developed at the seaside.

Working class men and women with their less sophisticated manners and open sexual behaviour shocked the more genteel middle classes. The danger was that those visitors and residents most valued by the town would either seek remoter areas or begin to travel abroad. That existential threat could never be tolerated.

By 1870 there were 48 places classified as seaside resorts, all attracting day-trippers as well as holidaymakers. Yet seaside towns were not all the same. While many of the Victorian visitors to other resorts were working class, Torquay saw itself as the premier retreat. With no major centres of industry in close proximity, it was able to target the more affluent visitor, relying on its reputation of being an area of great natural beauty and as a health resort. Torquay consciously targeted a more upmarket clientele, ranging from middle class artisans to prominent members of society, such as Oscar Wilde, Lord Lytton, Baroness Burdett-Coutts (pictured below), and Rudyard Kipling. The town consequently adopted the names familiar to the elite clientele it was trying to attract – Grosvenor, Pimlico, Belgravia.

Recognising that resorts could cater for different classes of visitors, a strategy of diverting the lower classes to other resorts was undertaken. Entertainment was targeted and the prices charged by the hotels and boarding houses was higher in Torquay than Paignton. It was further implied that lower standards of behaviour would be permitted in other resorts. For example, it was believed that postcards prohibited in Torquay were acceptable for sale in neighbouring towns.

It wasn’t until 1902 that Torquay introduced its first advertising campaign to market to summer tourists. But this was also a diversion strategy to segregate and separate the different classes of visitor. Torquay was promoted as an autumn and winter resort deliberately to offset the spasmodic conditions of the holiday trade with the late holiday season focussed on the middle or upper-classes. To attract this clientele we needed to offer comfort, the ‘right tone’ and specific entertainments. Such amusements were based on seasonal patterns reflecting the nature of the intended audience. As cultural forms, however, they would often fail to evolve and innovate. They didn’t need to as there would always be a new audience every two weeks.

One activity laden with meaning was to ‘take the cure’, a pseudo-scientific practice that advocated immersion in sea water for physical and mental health. This practice was regulated and involved modesty and bathing machines. Covered completely, women would descend from the bathing machines that had been driven into the water, immerse themselves and then travel back to the beach. While swimming costumes and swimming by people of lower classes became more popular, men and women still had to bathe separately, a practice that wasn’t altered until the year Victoria died in 1901.

Local authorities also drew the line of acceptable behaviour in other areas such as Sunday observance – hence the ‘Torquay War’ when the Salvation Army tried to march on the Sabbath, a six month conflict which led to over a hundred arrests and rioting before the Council relented.

Now everybody likes to spend their summer holiday

down beside the side of the silvery sea.

I’m no exception to the rule, in fact, if I’d me way,

I’d reside by the side of the silvery sea.

So Torquay welcomed a certain type of visitor. But not all visitors would return home. Many came to settle, retire or just to seek a better life. Over the years the town’s young and ambitious would leave to be replaced by the retired, the comfortable and those looking for a better life. This gave Torquay an unbalanced community. By the late nineteenth century women far outnumbered men: in 1871 there were 12,772 females to 8,885 males. And by the late twentieth century there would also be a growing age imbalance as the Bay’s retired community increased.

Demand for housing and for tourist accommodation led to the suburbanisation of the coastline as holiday camps, hotels and bungalows grew along the edges of the Bay. This took place in a period of only limited planning before the introduction of the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act.

By 1911, 55% of English people were visiting the seaside on day excursions while 20% were talking holidays requiring accommodation – in 1949, five million holidaymakers crowded Britain’s resorts.

It looked like the British seaside resort had a great future. Torquay in particular was affluent, with its own comfortable identity, stable local government, and a place at the pinnacle of British tourism. But this time the future of the town wouldn’t be in its own hands. On the 5th of May 1962, the first fare-paying flight of the new British airline Euravia took off. This was something new – the all-inclusive tour to an unheard of town by the name of Palma de Mallorca. So began the next phase in Torquay’s history…

//pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/js/adsbygoogle.js

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

You can join us on our social media pages, follow us on Facebook or Twitter and keep up to date with whats going on in South Devon.

Got a news story, blog or press release that you’d like to share or want to advertise with us? Contact us