The police recently raided a Torquay house and found cannabis plants to the value of £12,000 growing in two bedrooms. They also found over £2,000 in cash, phones, scales, heaters and a small amount of ecstasy. The amateur indoor gardener admitted production and was given a 10 month suspended sentence. And so the Bay’s forever war on cannabis continued.

While alcohol has always been the popular drug of choice for local residents, narcotics have been a feature of the town for two centuries. An estimated five out of six Victorian working class families used opium on a regular basis, while many famous residents and visitors freely used a variety of drugs that are illegal today.

A less familiar intoxicant for Georgian visitors to Torquay was cannabis. Although the use of cannabis is believed to stretch back 4,000 years, it only garnered real popularity when William Brooke O’Shaughnessy, who encountered the drug while working as an East India Company medical officer, brought a quantity back with him when he returned from India in 1842.

Cannabis was soon regarded as a wonder drug and became one of the secret ingredients in patent medicines. As Torquay was a health resort, cannabis became widely used, though this enthusiasm was short-lived. The introduction of new drugs such as aspirin and the invention of the syringe and injectable medicines caused a decline in its therapeutic employ.

Inevitably there was recreational use. In Torquay this appears to have been largely confined to a small group of prosperous initiates, the early enthusiasm coming from an interest in the Orient. Romantics believed that nature held secrets of which man knew little and so natural compounds were presented as a doorway into secret knowledge and the creation of great works of literature. Torquay was also a centre for the occult, Spiritualist séances were common, and cannabis was seen as a way to “expand the human mind” and to peer into the spirit world.

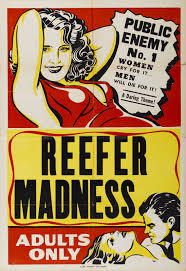

Cannabis was only made illegal in 1928. This followed an international drugs conference in Geneva when an Egyptian delegate convinced everybody that the drug was as dangerous as opium.

Of course, cannabis use didn’t end and it became increasingly popular during the fifties when migrants from the Caribbean arrived; the scene introducing white jazz musicians. The first drugs bust was in 1952 at the Number 11 Club in London’s Soho.

Despite minimal use of cannabis in Torquay in the post-war period, this would change. While political beliefs had always divided local opinion, after the Second World War came the ‘Generation Gap’. This found some young people rejecting the value system of their parents’ generation in a new form of rebellion. This was manifested in lifestyle choice rather than in traditional right-left politics, and unfamiliar social fractures were soon to be seen. In September 1964 the President of Torquay Trades Union Council complained that,

“I did not think that in the twentieth century we would have people who would walk about literally stinking. Bohemians and their unhygienic habit of sleeping rough on the beaches, and lounging on street corners, wearing al fresco attire and no shoes and ganging together to block pavements to pedestrians.”

The focus of the union’s hostility were men and women who represented a new counter-culture. They had found a welcome in the back-street Melville Inn and the Rising Sun after being barred from sea-front pubs. Local author and musician Mike Williams was a part of that nonconformist community:

“In Torquay, the beatnik lifestyle was mainly one of part-time work, the cheapest possible rented rooms, support from the National Assistance Board, and loafing about on beaches and in pubs. We worked in hotels, on the beaches, on the buses, even sometimes in offices.”

Despite the town’s long history of use and indulgence, the radicalism of the counter-culture saw a variety of substances, including new semi-synthetics such as LSD, becoming negatively identified with dangerous social change. Conflict with the authorities was inevitable and often centred around their use.

Particularly emblematic was recreational cannabis. This was a new dividing line, and the drug took on a greater significance to become symbolic for both the counter-culture and the authorities.

Across the nation, cannabis arrests increased dramatically: from 235 in 1960 to 4,683 by the end of the decade. By 1973, possession convictions had reached over 11,000.

At 9.30pm on April 12, 1969, seventy members of Torbay’s Drugs Squad conducted a raid on Belgrave Road’s Rising Sun Inn. This was the first action of its kind and seventeen people were arrested, sixteen for possession under the Dangerous Drugs Act and one for wilfully obstructing Police Constable James Copeland.

The police had split into groups, each with the task of entering a different bar in the crowded pub. Using a megaphone the police ordered all the men to either put their hands on their heads or lapels and the women to cross their arms. Twenty-year-old John S of Teignmouth Road refused and told the Police: “This is silly… if you want them raised, you can raise them… you can’t mess me about like this. I want to see a higher authority”. He was arrested and, even though he had no trace of drugs on him, he did have three previous convictions for allowing premises to be used for the smoking of cannabis. In what might be seen as an example of heavy sentencing, the presiding magistrate described refusing to cooperate with the police as a “serious offence” and John was sentenced to six months imprisonment, suspended for two years.

In July 1969 the police warned pub landlords to be on the lookout for anyone smoking “oddly shaped cigarettes”, telling pharmacists to be wary of customers who appeared to be “dozy, dirty, nervous, irritable or just not quite right”. Later that year they issued a statement saying they were keeping an eye on “local hippies”.

Friction between the hippies and officialdom intensified as the easy-going 1960s bled into the disenchanted 1970s. In early 1970 the police told the Torquay Times that the town had a drugs problem: “The drug takers are mostly young people coming down here because it is a nice place. There is plenty of accommodation and they can get casual jobs in bars, holiday camps and hotels.”

Local hippies had been complaining about the attitude of the authorities for years and believed that the town’s dependency on tourism generated a heightened intolerance of any non-standard behaviour. In March 1970 an anonymous 21-year-old spokesman for the hippies claimed that the police were harassing them in order to break up their community before the influx of summer visitors. He said his flat had been raided and that the police were putting pressure on landlords to turn him and his friends out of their homes:

“They are also tightening up on the places where we meet – trying to get them to close down or to refuse to serve us. They are using the stop-and-search powers more. They’ll stop anyone who dresses differently or who has long hair.”

The pretext for stop-and-search was usually the quest for cannabis and there would be a backlash. As the sixties ended, the mood noticeably changed. In 1972 a hundred-strong mob of men and women attacked Torquay police station, throwing bricks and bottles. The chant was “Kill the Pigs!”. Officers were assaulted, one later telling the court he thought he was going to die.

In 2021 cannabis remains a Class B drug, meaning simple possession of a small amount can lead to a prison sentence of up to five years, while growing or selling cannabis can result in a sentence of up to 14 years. Legal penalties have, however, failed to eliminate its use. In 2019/20, 29.6 percent of people aged between 16 and 59 had used the drug at least once during their lifetime.

This makes strict enforcement of the law impossible and so an unofficial policy began of not prosecuting for straightforward possession. Accordingly, the number of possession offences in 2019 saw a 30 percent decrease from that of 2009.

So we have the authorities effectively looking the other way, tacitly recognising the reality of wide scale use. Meanwhile, much of the United States had permitted cannabis use, while European nations – such as the Netherlands with their coffee shops and Portugal’s decriminalisation – mostly adopted a liberal approach to recreational drugs.

Yet, the British system relies on national legislation – local councils can’t change the law. The two-party system has both parties appealing to older socially conservative voters, with neither risking the charge of being seen to be “soft on drugs”. And so the current arrangement seems to be going to continue.

So who are the kinds of people who buy and consume this drug? We fortunately do have a range of past cannabis consumers who have admitted a youthful indiscretion. They include: Boris Johnson, David Cameron, Matt Hancock, Andy Burnham, Nicola Sturgeon, Dominic Raab, Jeremy Hunt, and Ruth Davidson