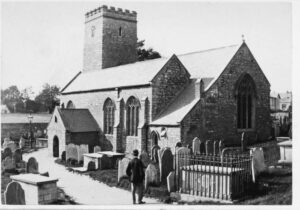

Just off Torquay’s Lucius Street is the Greek Orthodox Church of St. Andrew. It was at the heart of the oldest settlement of what would become Torquay.

It’s believed that the founding of the church, which was to be named St. Saviour’s, was in the sixth century and may have been on an even older site. It was dedicated to St. Petrox, a Celtic saint, and was located next to a spring, wells being particularly significant to pre-Christian religions.

The first written account of the parish occurs in the Domesday Book in 1086, while the church we know today was built in the fourteenth century on the site of an earlier Norman chapel.

The first written account of the parish occurs in the Domesday Book in 1086, while the church we know today was built in the fourteenth century on the site of an earlier Norman chapel.

Though the church itself is an iconic building, it’s the churchyard itself that we’re interested in here. Specifically, a single example of its 690 recorded graves.

Dating from 1697, it’s one of the oldest in the graveyard and has attracted interest for many years. That’s because it features a skull-and-crossbones. This has caused some people to believe that it’s the grave of a local pirate.

The convention of featuring death’s heads on gravestones is quite common. This image is called a Memento Mori, which is Latin and translates as ‘Remember that you will die.’

Such gravestones came from a different time when our relationship with death was far more intimate than today. Seventeenth-century life expectancy was only about 35 years, largely because of high levels of infant and child mortality. Accordingly, the deaths of the young were an ever-present reality. Also, not only were you born at home rather than a hospital, but you usually died there. Your family would handle the preparation of your body. And there you would lie until your funeral.

And so, graveyards shouldn’t be seen as merely a record of those who came before us. They are visual markers of how death was seen in the past. Gravestones can give us a window into how our ancestors saw their lives and what they held as important. They carry messages and they evolve as we changed our view of life and what came after.

And so, graveyards shouldn’t be seen as merely a record of those who came before us. They are visual markers of how death was seen in the past. Gravestones can give us a window into how our ancestors saw their lives and what they held as important. They carry messages and they evolve as we changed our view of life and what came after.

If we look at that 1697 memorial, we note that the death’s head is not a Christian symbol. It was designed by a person of a puritan persuasion. Puritans did not advocate using traditional Christian images, such as cherubs, Christ figures, or crosses on their gravestones, in their meetinghouses, or on church silver. They were resolutely against attributing human form to God, angels, or spirits.

But they did believe that contemplation of mortality was good for the soul. And where better to be reminded than on the tombstones of their loved ones.

Churches and their graveyards were the centre of the community. In a society where few could read or have access to books, they were utilised as places where teaching would take place. Images used by the clergy as aides to instruct on good Christian behaviour. And so, those death’s heads were a warning to the living rather than the deceased upon whose headstone they were engraved. The message here was that you will someday be as they are, just dust in the grave.

The message here was that you will someday be as they are, just dust in the grave.

The death’s head was the most obvious symbol of death, mortality, penitence, and sin. Some gravestones are more explicit and included the Latin instruction. Other solemn epitaphs prompted passers-by to contemplate mortality and the fleeting nature of life on earth.

Accompany the death’s head on seventeenth and eighteenth-century gravestones could be bells or coffins. An hourglass reinforced the message that time is running out; a winged hourglass indicating that ‘time flies’.

A development was the winged skull, symbolic of how the soul is freed and taken up into the afterlife. Or perhaps the scythe, with a figure of Death as a robed skeleton. In a rural society, the scythe was ever present and occurs in legends of sacrifice. Somewhat softening the message are stars, vines and flowers, indicating that life goes on.

A development was the winged skull, symbolic of how the soul is freed and taken up into the afterlife. Or perhaps the scythe, with a figure of Death as a robed skeleton. In a rural society, the scythe was ever present and occurs in legends of sacrifice. Somewhat softening the message are stars, vines and flowers, indicating that life goes on.

The central idea behind the Memento Mori was pre-Christian. It stated that one day you will fail and die, so don’t get arrogant. This warning against hubris is part of a long tradition that goes back to at least classical times. The highest honour bestowed upon a victorious general in the ancient Roman Republic was the ‘triumph’, ‘triumphus’ in Latin, a ritual procession that was the summit of a Roman’s career. However, a slave held a golden crown over the general’s head while repeatedly reminding him in the midst of his glory that he was a mortal man. He may be victorious today, but who knows what tomorrow will bring.

The use of these motifs of mortality on memorial monuments became popular in Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and appears to derive from the ‘Danse Macabre’ or the ‘Dance of Death’.

Following the Black Death in the fourteenth century, the Danse Macabre emerges as an artistic type of allegory. It could be seen in art, drama, literature, or music, and typically represented a procession or dance of both living and dead figures. The personification of Death is shown as he summons representatives from all walks of life to dance along to the grave. Typically illustrated is a pope, emperor, king, child, and a labourer, reminding all their mortality.

Following the Black Death in the fourteenth century, the Danse Macabre emerges as an artistic type of allegory. It could be seen in art, drama, literature, or music, and typically represented a procession or dance of both living and dead figures. The personification of Death is shown as he summons representatives from all walks of life to dance along to the grave. Typically illustrated is a pope, emperor, king, child, and a labourer, reminding all their mortality.

People even carried with them reminders of how insecure life could be.  A Memento Mori pendant was unearthed in the grounds of Torre Abbey. It takes the form of a skeleton in a coffin. This is ‘The Torre Abbey Jewel’ and dates from around 1540. It is made of gold, enamelled in white and black, with the remains of opaque pale blue, white, yellow, translucent green, and dark blue enamel on the upper scrollwork. It was hung around the neck on a chain and meant to daily remind the wearer of the inevitable. The pendant is on display at The Victoria and Albert Museum (pictured above).

A Memento Mori pendant was unearthed in the grounds of Torre Abbey. It takes the form of a skeleton in a coffin. This is ‘The Torre Abbey Jewel’ and dates from around 1540. It is made of gold, enamelled in white and black, with the remains of opaque pale blue, white, yellow, translucent green, and dark blue enamel on the upper scrollwork. It was hung around the neck on a chain and meant to daily remind the wearer of the inevitable. The pendant is on display at The Victoria and Albert Museum (pictured above). The use of the kind of mortality symbols we see in Torre churchyard declined sharply after 1760 as views on religion changed. We become more enthusiastic about the rewards of Heaven than the horrors of Hell. Gravestones then began to feature the cross and other symbols of salvation and resurrection.

The use of the kind of mortality symbols we see in Torre churchyard declined sharply after 1760 as views on religion changed. We become more enthusiastic about the rewards of Heaven than the horrors of Hell. Gravestones then began to feature the cross and other symbols of salvation and resurrection.

Notwithstanding the evolution in approach some of us carried on with the same, frankly depressing, message.

in 1854, Jane Burgoyne died in Torquay at the age of twenty-five. Her epitaph in Torre churchyard reads:

“Weep not dear husband and friends most dear,

I am not dead but sleeping here,

the grass is over my grave you see,

Prepare for death and follow me.”

Now Memento Mori, so important for generations of local folk, are barely remembered. There are some local survivals, however. The skull-and-crossbones was taken up by the Romantic movement and in the twentieth century by the Goths. Its ability to inspire fear was also utilised in the Jolly Roger flag as we see in Brixham at certain times of the year.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon