Some folk in Torbay believe that the world is only a few thousand years old, that dinosaurs are fake, and that people like us have been around since the very beginning. The argument is that if it’s in the Bible then it must be literally true. This is, however, a fairly minority belief in the Bay – most local Christians tend to see the Scriptures as being written by men who used metaphors to get their point across.

The idea that the Old and New Testaments are the ‘Word of God’ himself is, of course, far more common in the United States. Over in Kentucky, for example, you can visit the Creationist ‘Answers in Genesis Museum’ and have an opportunity to help construct the new ‘Ark Encounter Park’. If you would like to get involved in recreating Noah’s Ark – alongside a decadent and titillating pre-Flood community which sounds far more interesting – you can start by sponsoring a plank for a hundred dollars. Here’s the, frankly barking, promotional video:

The idea that the earth is around 6,000 years old and knocked up over the course of a week is still going strong. There’s even a ‘Creation Science [sic] Hall of Fame’ – “Honouring those who honoured God’s word as literally written in Genesis” – which features the ‘scientific’ founders of Creation Science.

One of the most important founders was Torquay-resident Philip Henry Gosse (1810–1888). Born in England, Philip clerked in Newfoundland, farmed further inland in Canada, and taught school in Alabama – where he was appalled by the institution of slavery – before returning to England. He tried various careers, including running a school, but two things attracted his life-long devotion: the wonders of the natural world and the salvation of his soul.

Philip accordingly became a naturalist. He wrote more than 40 books and 270 scientific and religious articles, including ‘An Introduction to Zoology’ (1844) and a series on Natural History. In recognition of his scientific contributions, he was elected an Associate of the Linnaean Society (1850) and a Fellow of the Royal Society, London (1856). His greatest legacy, however, was as a popular writer of science for the general public.

He is credited with producing the first illustrated field guide on marine organisms to help the non-specialist identify and learn about animals (see above). In addition, Philip invented the first salt-water aquarium in which to observe and study marine organisms and he designed the first public aquarium, which opened in London in 1858.

Sadly, bearing in mind his great contribution to science, Philip is now best known as the author of ‘Omphalos’ in 1857. This book attempted to reconcile the immense geological ages presupposed by Charles Lyell with the Biblical account of Creation, which suggested that the world was six-thousand-years old. While his contemporaries worked out evolution, Philip worried about how to make all the things that science was learning fit neatly into a Biblical chronology. His efforts earned him the unsurprising disapproval of scientists and the criticism of many progressive Christians.

He rejected Charles Darwin’s ideas about evolution: “If any choose to maintain that species were gradually bought to their present maturity from humbler forms he is welcome to his hypothesis, but I have nothing to do with it”, he wrote.

Philip argued that in order for the world to be ‘functional’, God must have created the Earth with mountains and canyons and trees already with growth rings. He wrote, “It may be objected that, to assume the world to have been created with fossil skeletons in its crust – skeletons of animals that never really existed – is to charge the Creator with forming objects whose sole purpose was to deceive us. The reply is obvious. Were the concentric timber-rings of a created tree formed merely to deceive? Were the growth lines of a created shell intended to deceive? Was the naval of the created man intended to deceive him into the persuasion that he had had a parent?… I distinctively reply, No!”

Specifically, he worried about whether Adam, the first man, had a belly button – ‘omphalos’ being Greek for ‘navel’. Adam certainly didn’t need an umbilical cord, never having spent time in any woman’s womb but, as the prototype for all men, he should have come with all the parts. Philip came to the conclusion that Adam and Eve were created with hair, fingernails, and navels – the image (below) is of Claude-Marie Dubufe’s 1827 ‘Adam and Eve’ clearly showing the first man with an ‘innie’, along with some unfortunate genital greenery.

According to Philip, God had given things the appearances of a history that they had not experienced. Hence, all the geological strata and the fossils collected by Victorian scientists were false evidence of a gradual history that the world had never had. Accordingly, he stated that there was no truth in the claim that the earth was of any great age.

By rejecting the antiquity of the earth, and by challenging the validity of evolution, Philip has been seen by our Biblical literalist friends as the father of what today is called Creationism.

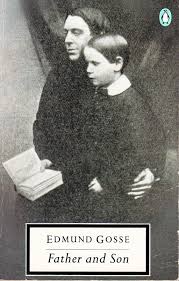

For over 30 years, Philip lived in Torquay. His son, Edmund Gosse (1849-1928) in his biography ‘Father and Son’ (1907) describes how, at the age of 8, the family moved from London to Torquay in 1857. Along with his father and governess, they took residence in Sandhurst, a villa in Manor Park, St Marychurch.

Edmund presents a picture of his father as a despotic and fanatically religious man. He tells of the narrowness of their life as members of the conservative evangelical Christian denomination, the Plymouth Brethren. Soon after his arrival in Torquay, Philip became the Brethren’s pastor and overseer of the Brethren meetings. At first, the meetings were held over a stable, but then in finer quarters, which Philip may have financed himself.

Giving an indication of the severity of his religious views, Philip refused to use the ‘St’ in St Marychurch and even gave his address as ‘Torquay’ so as not to have anything to do with the “so-called Church of England”. He also gave money to charity, especially to foreign missionaries, including ones sent to the “Popish, priest-ridden Irish.”

Philip Henry Gosse died at St Marychurch on August 23, 1888, at the age of 78, and was buried at Torquay Cemetery. He didn’t expect to die, however, but be lifted into heaven when Christ returned to earth.

Edmund (pictured above) took a very different path to his father. In ‘Father and Son’ he relates how, as a boy, he attended school in St Marychurch. Though he lived in such a strict religious household, Edmund secretly became familiar with nonreligious poetry, fiction, and other literature. On leaving Torquay, he secured employment on the library staff of the British Museum from 1865 to 1875, was a translator for the Board of Trade for some 30 years, and later lectured on English literature at Trinity College, Cambridge. Edmund was librarian to the House of Lords from 1904 to 1914.

He translated three of Ibsen’s plays, including ‘Hedda Gabler’ (1891) and ‘The Master Builder’ (1892). He wrote literary histories, such as ‘18th Century Literature’ (1889) and ‘Modern English Literature’ (1897), as well as biographies of notable writers.

In August 1875 Edmund married Ellen Epps (1850-1929), a young painter in the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Edmund and Ellen had a happy marriage lasting more than 50 years and they had three children. This was despite Edmund being gay – his series of gay love letters have been published. He wrote to a friend: “I have had a very fortunate life, but there has been this obstinate twist in it!”

One suspects his evangelical father may not have approved…