Bomb damage in Chelston’s Rosary Road in 1942.

During the 1930s, there was a desperate desire that the Great War must never be repeated. It was only twenty years since the horrors of the trenches. Could anyone be insane enough to want to do it all again?

British veterans believed they had an important role to play in making sure peace continued. To this end, the leaders of the British Legion embarked on several trips to Germany during 1935 to improve Anglo-German relations. The delegations were feted by Hitler, who flattered them with “spontaneous” welcoming crowds.

The future Edward VIII, the Legion’s patron, endorsed meeting with the Nazis. He told the 950 delegates at the Legion’s annual conference in London: “I feel that there could be no more suitable body or organisation of men to stretch forth the hand of friendship to the Germans than we ex-servicemen who fought them in the Great War and have now forgotten about all that.”

The photos show British Legion chairman, Major Francis Fetherston-Godley, meeting Hitler (above and below) and Hermann Goering showing off his archery skills for the visitors.

The Legion even visited Dachau concentration camp during one of these visits, followed by a family supper with Heinrich Himmler of the SS. The Legion party was told that Dachau’s 1,500 inmates included 1,000 political prisoners but they were assured that they all enjoyed a healthy life. By the end of the war there were 32,000 known deaths at the camp, and thousands more that were undocumented.

There were voices within the Legion that objected. In November 1935, the former Senior Jewish Chaplain with the British Forces in France wrote a letter highlighting the growing persecution of Jews in Germany, “We Jews earnestly hope that the authorities of the Legion will make it perfectly plain to the ex-soldiers of Germany that, whilst justice and liberty are denied to the Jews of their country, the Legion must strongly disapprove of this policy.”

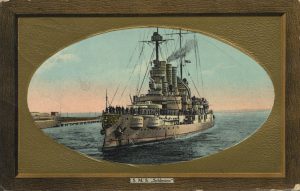

The Legion’s visits were organised by Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s ambassador to Britain (pictured above). In April of 1937 von Ribbentrop visited Torquay along with the German battleship SMS Schlesien (pictured below) as part of the same Nazi a charm offensive. A crowd of 300 met the Nazi party at Torquay Station and then the visiting dignitaries were driven to a reception at the Marine Spa – now Living Coasts. Ribbentrop, Frau Ribbentrop, Naval Attaché Admiral E Wassner, commander of the Schlesien Captain von Seebach, the German Vice Consul at Plymouth Mr Carlile Davies, and a number of ships officers were introduced by the Mayor Mr A Denys Phillips to members and officials of the Town Council. The crew of the ship later went on to play Torquay United in a testimonial match. There’s a photo of the sailors giving a Nazi salute just before the game which United won.

By the summer of 1938, Germany had remilitarised the Rhineland and annexed Austria. Hitler then demanded the German-speaking Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia. The British attempted to mediate and proposed a neutral force to oversee a plebiscite. The Legion was then asked to provide 1,200 men for the job. In response, in October 1938 the Torbay area contingent of the British Legion’s ‘Peace Army’ sent 11 volunteers. These included four Torquay members, including a Victoria Cross winner who lived in Falkland Road. However, Hitler was never serious about negotiation. The plebiscite proposal foundered, and the British contingent was disbanded after only 10 days, three of them spent on a ship anchored off Southend.

When Czechoslovakia was invaded by the Germans in early 1939, the British Legion finally accepted that Hitler was not to be trusted. Hitler’s intentions were clear and the Legion turned down an invitation to an ex-servicemen’s conference in the Black Forest.

Yet in 1938 there was still hope. A yearning for peace continued and was to be found in the unlikeliest of places. For example, in September 1938 the Palm Court (now Abbey Sands and pictured below) hosted the annual conference of the Florists Telegraph Delivery Association. Over 200 people were present, including the Mayor and Mayoress of both Torquay and Plymouth, to see “Exquisitely-shaded single and double gerberas (a rare South African flower), lilies of the valley and every imaginable shade of roses and carnations… among the flowers to the value of £60 which decorated the dining room of the Palm Court Hotel.”

The looming conflict wasn’t the only topic of concern, however. The president of the association warned of the dangers of artificial flowers. He had heard, “from time to time of people who had the audacity to think they could ‘paint the lily’. That was not the way to increase trade: artificial things might satisfy for a short while, but they would not last. There was no substitute for real flowers, real beauty or real flower smells.”

The gathering clouds of war couldn’t be ignored, even amongst the carnations and azaleas. Even at this late date, there were grounds for optimism. Dr HV Taylor, Commissioner of Horticulture at the Ministry of Agriculture told the gathered florists, “When I left London this morning it was with a very despondent heart. The whole thing looked black, and then I read the papers and could see that things were not as black as they were painted. I think now that most of the danger has passed away.”

Similarly looking on the bright side was the Mayor of Torquay, “I congratulate you on going steadily on with your conference, despite the war clouds hanging over us. If we hope for the best and work for the best there will be greater possibilities in the meetings which are taking place at Munich during the next few days.”

He then congratulated the association on their wonderful system of ordering flowers by telegraph and having them delivered promptly all over the world. “To prove that this could be achieved, Mr J Hunt, the association’s president, declared that a proposal by the Mayor would be carried out immediately. Flowers would be sent to Mr Chamberlain, Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini. This announcement was received with great applause from the audience.” Unfortunately, no records exist of whether Herr Hitler appreciated the gift. It clearly failed to avert war which broke out twelve months later.

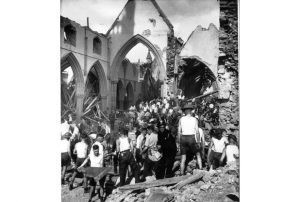

When war did come, Torquay was seriously affected. According to a log kept at St Marychurch Fire Station, between 1939 and 1945 Torquay suffered 21 German raids- pictured left is bomb damage in Babbacombe. The largest attack involved 23 enemy aircraft of which 11 were destroyed. during the war 161 bombs of various types were dropped, causing 165 deaths and over 150 civilian casualties and “several military” – at the time the numbers of military casualties was not revealed. There were 643 air raid alerts, 125 buildings were destroyed and 11,615 damaged. Particularly tragic was the Rogation Sunday attack which destroyed the Parish Church at St Marychurch causing the deaths of 21 children on Sunday, May 30 1943 (pictured below).

Another major incident was the raid of October 25 1942 which commenced at 11.02. Four German fighter bombers first dropped two bombs on the Palace Hotel (pictured below) which was being used as a hospital – despite there being a large red cross painted on the roof. The casualties included Home Guards on exercise and convalescent RAF officers –19 were killed, 45 injured with 1 missing. They then went on to bomb, cannon and machine gun Babbacombe, St Marychurch and Hele – where a gas holder was set on fire. In all, four high explosive bombs were dropped, three houses were destroyed and two badly damaged. At the end of the day, 37 people had died with “many casualties”.

No matter how futile the attempts to avoid war now seem, we can’t criticise those for trying to avert the conflict. They mostly acted in good faith and can’t be blamed for not comprehending the forces that reason would face over the following six years.