Public toilet, lavatory, bog, public convenience, khazi, loo, the ladies and gents, the water closet, and other, less polite or regional, appellations. By any other name would smell as sweet.

That we have so many slang and euphemistic terms about the toilet and the ways we use it suggests our British sensitivities. And this is nothing new. Shakespeare and Chaucer included scatological humour in their writing. We even have graffiti, ‘latrinalia’, an anti-art form inscribed on lavatory walls in the form of pictures or words. Always anonymous, sometimes witty or political, often pornographic.

Public toilets have consequently always been politicised places. They arouse intense debates around where they should be, who uses them, for what purpose, and whether they should be there at all.

Public toilets have consequently always been politicised places. They arouse intense debates around where they should be, who uses them, for what purpose, and whether they should be there at all.

Before the introduction of the public lavatory to the Victorian town, Torquay’s streets and parks were fouled by human waste. And the situation was getting worse as the population increased from 5,982 in 1841 to 11,474 a decade later.

Foul smells were increasingly recognised as being more than just unpleasant, with poor sanitation linked to disease. In 1849 sixty-six people died from cholera and dysentery over a period of six weeks. Many of the dead were buried in Cholera Corner in the churchyard of St. Andrew’s off Lucius Street. As was to be expected, the cases occurred mainly in the oldest and poorest districts of Pimlico and Swan Street.

Legislation was passed by Parliament in the form of two public health acts, in 1848 and 1875. In the 1860s, Louis Pasteur demonstrated the relationship between microorganisms and infectious disease, causing a huge shift in thinking about illness and sanitation.

Demand for public toilets came as part of that wider need for better provision of sewers and clean drinking water. Both the technology and the model to work to came in 1851 when the plumber George Jennings installed what he called ‘monkey closets’ to the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Also known as ‘retiring rooms’, they included separate amenities for men and women and were the first flush toilet facilities.

Demand for public toilets came as part of that wider need for better provision of sewers and clean drinking water. Both the technology and the model to work to came in 1851 when the plumber George Jennings installed what he called ‘monkey closets’ to the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Also known as ‘retiring rooms’, they included separate amenities for men and women and were the first flush toilet facilities.

People paid a penny to use them and so was born the concept of ‘spending a penny’. This payment ensured patrons received a clean seat, a towel, and a shoeshine. The standard had been established. The next year, London’s first public toilet facilities were opened and known euphemistically as Public Waiting Rooms.

The public toilet then began to appear in cities and towns that prided themselves on being modern and affluent. By the late Victorian era many businesses and local authorities were providing public conveniences in workplaces, railway stations, parks, shops, pubs, restaurants, and other places. The toilets that were municipally owned or managed were usually entered directly from the street. Some public toilets were free of charge while others charged a fee.

Of course, Torquay, which looked to the capital for many of its target visitors, was amongst the first towns to embrace the innovation. Yet, while progress in public sanitation undoubtedly helped to improve the cleanliness and health of the town, provision wasn’t being implemented equally. Indeed, the presence of public toilets consistently reflected class and gender inequalities in the resort.

Of course, Torquay, which looked to the capital for many of its target visitors, was amongst the first towns to embrace the innovation. Yet, while progress in public sanitation undoubtedly helped to improve the cleanliness and health of the town, provision wasn’t being implemented equally. Indeed, the presence of public toilets consistently reflected class and gender inequalities in the resort.

Local authorities were not legally required to provide public toilets. However, the Board, and later the Council, had close links to the tourist industry and so supported any amenities that would attract and retain the ‘right type’ of visitor. The prosperous also arrived expecting certain facilities beyond those offered by their hotels and rented villas. It further made economic sense for traders who didn’t want tourists to have to regularly return to their accommodation.

The wealthier suburbs of Torquay also provide toilets to entice visitors away from the town centre. Hence, for example, both Higher and Lower Chelston had public toilets. In contrast, the town’s less affluent areas had less provision.

The wealthier suburbs of Torquay also provide toilets to entice visitors away from the town centre. Hence, for example, both Higher and Lower Chelston had public toilets. In contrast, the town’s less affluent areas had less provision.

In Victorian towns, public lavatories were often built beneath urban streets or public buildings. These subterranean toilets took up minimal space, were accessible by stairs, and often lit by glass bricks on the pavement. They also helped to hide ‘objectionable contrivances’ from view. Torquay’s examples include those at Brunswick Square (pictured below), Castle Circus and the part-underground facility at the top of Lucius Street..

Local health boards built public toilets to a high standard, some being maintained and policed by an attendant, a lucrative position in a place where gratuities were plentiful. Think of Dan Dann, the lavatory man, played by Charles Hawtrey in Carry on Screaming (1966).

Local health boards built public toilets to a high standard, some being maintained and policed by an attendant, a lucrative position in a place where gratuities were plentiful. Think of Dan Dann, the lavatory man, played by Charles Hawtrey in Carry on Screaming (1966).

Significantly, however, most early public toilets were solely for men. Victorian society was gender segregated, with the public sphere for men and the private sphere for women and so female conveniences were simply not provided. Female toilets were also viewed as somewhat distasteful which ensured that women never travelled much further than where family and friends resided. This restriction became known as the ‘urinary leash’ where inadequate toilet access curtailed access to leisure, politics, and employment.

Significantly, however, most early public toilets were solely for men. Victorian society was gender segregated, with the public sphere for men and the private sphere for women and so female conveniences were simply not provided. Female toilets were also viewed as somewhat distasteful which ensured that women never travelled much further than where family and friends resided. This restriction became known as the ‘urinary leash’ where inadequate toilet access curtailed access to leisure, politics, and employment.

In response, the Ladies Sanitary Association was formed and campaigned from the 1850s onwards. The significance of the campaign was recognised by both sides of the argument.

Some men opposed the siting of women’s toilets next to the men’s and even engaged in sabotage. On the other side of the debate, Torquay’s Suffragettes were very aware of the practical and symbolic need for equal provision.

Some men opposed the siting of women’s toilets next to the men’s and even engaged in sabotage. On the other side of the debate, Torquay’s Suffragettes were very aware of the practical and symbolic need for equal provision.

Gradually the provision of facilities for women improved. Ladies Rooms began to appear in theatres, railway stations and many other places. Local businesses quickly realised that it made financial sense to keep female shoppers in their premises as long as possible. This offer, on the other hand, didn’t apply to those women without spending power.

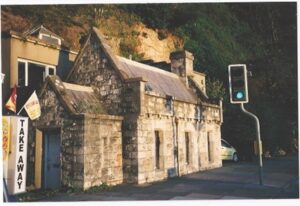

The twentieth century saw Victorian squeamishness fade. It then became a component of our tourist strategy to advertise the public toilet and to reassure visitors that they could spend all day on the beach or shopping and that their toilet needs could always be met. Public conveniences accordingly became much more visible. Note the public toilets at Corbyn Head and the conversion of the old Toll House on Rock Walk.

The twentieth century saw Victorian squeamishness fade. It then became a component of our tourist strategy to advertise the public toilet and to reassure visitors that they could spend all day on the beach or shopping and that their toilet needs could always be met. Public conveniences accordingly became much more visible. Note the public toilets at Corbyn Head and the conversion of the old Toll House on Rock Walk.

Nevertheless, public toilets persist as a focus for moral panics, with exaggerated perceptions exceeding any actual threat. Hence, we have seen, in some cases, cash-strapped councils opportunistically responding to social concerns about behaviour in toilets to justify closing them altogether.

One anxiety was around ‘cottaging’, gay men using public toilets for sex. During the later twentieth century the police even used ‘pretty policemen’ to entrap gay men, a practice that increased after the 1967 Sexual Offences Act permitted homosexual acts between consenting adults.

One anxiety was around ‘cottaging’, gay men using public toilets for sex. During the later twentieth century the police even used ‘pretty policemen’ to entrap gay men, a practice that increased after the 1967 Sexual Offences Act permitted homosexual acts between consenting adults.

More recently the homeless and problematic drug users have been routinely used as an excuse to close toilets. All these are interventions that focus on a minority but then, inevitably, reduce services for the majority.

Across the nation, the number of public toilets has fallen by 20% since 2015 , a loss that leads to health and mobility inequality issues for many. One in five people state that a lack of facilities nearby can restrict outings from their homes, particularly an issue for the elderly and disabled. Over half of the public restricts fluid intake due to concern over the lack of toilet facilities, a strategy which can have serious health ramifications.

While we still have some public amenities in Torquay, we have partly privatised going to the toilet. Shops, bars and restaurants are now expected to fill in the gaps. But you usually have to spend money. This may be achieved by purchasing a coffee which largely defeats the object, or by pretending to be a paying customer of Green Ginger.

While we still have some public amenities in Torquay, we have partly privatised going to the toilet. Shops, bars and restaurants are now expected to fill in the gaps. But you usually have to spend money. This may be achieved by purchasing a coffee which largely defeats the object, or by pretending to be a paying customer of Green Ginger.

But not all toilet users are welcome. Now, after an absence of a century and a half, human waste is again to be encountered in the alleys around Castle Circus.

And so the debate over our public toilets has gone full circle. Both the old Torquay stench and the urinary leash have returned.

‘Torquay: A Social History’ by local author Kevin Dixon is available for £10 from Artizan Gallery, Lucius Street, Torquay, or:

https://www.art-hub.co.uk/product-page/torquay-a-social-history-by-kevin-dixon