“Work is the curse of the drinking classes.” Torquay visitor Oscar Wilde

Torquay folk have been in love with alcohol for a very long time. It’s an intimate affair that can be life-affirming abut also deeply damaging. Perhaps as a species we’ve always been in love – chemical analysis of jars from a Chinese Neolithic village revealed traces of alcohol from a fermented drink made of grapes, berries, honey, and rice from 7000BC.

But beer was always Torquay’s drug of choice, its consumption a popular pastime, and originally given freely to anyone who could afford to buy – including children of any age. Before we were even a town Torre Abbey’s abbots were brewing virtually all local beer of good quality, though gradually home breweries became inns and taverns to provide sustenance for travellers.

The first record we have of our imbibing history comes in 1774 when Exeter printer Andrew Brice wrote in his Grand Gazetteer that, “at Tor Kay is a village and an inn or two”. Actually, there were five “houses of entertainment” on Torquay harbourside servicing a population of around 500. They were licensed “for man and beast”.

By the mid-nineteenth century this had increased to 48 drinking establishments available for Torquay’s population of 11,400. These venues didn’t just give us an opportunity to get tipsy. Beer was good for you. It was seen as a food and could be stored longer than grain or bread without fear of pest infestation or rotting. Beer was boiled, contained bug-killing yeast and alcohol, so it was less likely to kill you than the local water which often came from the polluted River Fleet which still flows beneath Fleet Street. Contaminated water was a serious health issue – in the churchyard of St. Andrew’s on Lucius Street (pictured below) there’s a mass grave known as Cholera Corner, dating from 1849 and used to quickly manage the burial of 60 victims of that terrible water-borne disease.

Beer was certainly healthier than the other drink on offer. This was gin, invented in Holland around 1650 by distilling grain with juniper berries. Gin was cheap, flooded the market and led to the Gin Epidemic which lasted for 30 years and killed thousands – “Drunk for one penny, dead drunk for two,” they said. Eventually gin consumption waned as beer became better and cheaper, and tea and coffee became available.

It’s often been said that we drink in different ways to our continental neighbours and American cousins. One who quickly noticed this was the Canadian Isabella Cowen who visited Torquay in 1892 – she called us, “the land of formality and conventionalism”. While she was here she wrote a diary and noted that many of us drank with the sole intention of getting drunk and that public insobriety was more or less accepted. She was deeply shocked by Torquay’s, “men and women whose bleary eyes and blotched complexion betray their liking for the inebriating cup. Intemperance is too common a vice here and too fruitful of the misery both here and elsewhere to be made light of. As long as an Englishman can keep upon his feet he is considered quite respectable.”

Why we drink this way isn’t clear though it could be associated with our climate. Two European cultures seem to have emerged. Under the southern Mediterranean Roman model, watered-down wine was consumed with food and drunkenness was unusual. In our Iron Age and Germanic culture, on the other hand, heavy ‘feast drinking’ consumes alcohol drinks based on grains, not grapes, and we generally drink away from the dining table. We prefer heavy episodic drinking, but also days or weeks of abstinence. Unpredictable weather gave us lean years for the grains or honey from which alcohol was made so we learned to drink when it was available and to imbibe to celebrate – note how, compared to British pubs, American bars seem depressing places with male drinkers sitting alone. Lack of sunlight may also make people more depressed and susceptible to heavier drinking in winter. We self-medicate when we want to.

Yet, alcohol wasn’t the only recreational drug available in Torquay. An estimated 5 out of 6 working class families used opium on a regular basis in Victorian England, and many of Torquay’s famous residents and visitors freely used a variety of drugs that are illegal today. Opium was the standard medication for almost everything – the Victorian version of aspirin – and ‘social’ use was tolerated. Indeed, it was actually preferred because it didn’t produce the violence associated with alcohol. It was quite acceptable for teetotal Torquay ladies to use opiates instead of alcohol.

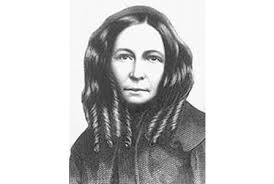

It seems that only later did people realise that opium use was habit forming For example, poet Elizabeth Barratt Browning (pictured above) who lived on Torquay Harbourside was a long term user of opium. She began her use of the drug when she was fifteen to treat the pain from a spinal injury complicated by “nervous hysteria”. She wrote: “My opium comes in to keep the pulse from fluttering and fainting…to give the right composure and point of balance to the nervous system. I don’t take it for ‘my spirits’ in the usual sense; you must not think such a thing.”

As Torquay grew rapidly crime, poverty and high infant mortality increased. Gross overcrowding in Pimlico and Swan Street was the root cause, but alcohol took a lot of the blame and became seen as a threat to order and efficiency. Drunkenness, and the related loss of self-control, was associated with the lower classes and a cause for concern. Along with of ongoing disorder in and around Torquay’s pubs and beer houses, drink was linked with riots in the town in 1847, 1867 and 1888. Alcohol was further seen to divert local people from good ways and opening up opportunities for other vices such as gambling and the temptations offered by Torquay’s hundreds of prostitutes. One man particularly concerned was the Vicar of Ellacombe, the Reverend CE Storrs, who in 1895 gave a sermon on the topic. “If Christ came to Ellacombe,” he thundered, “He would see indifference and unbelief more than ever He suffered on earth before. He would find the evil of intemperance rampant. He would meet it everywhere. He would see drunken crowds and sottish selfishness. If Christ came to Ellacombe and did a miracle, instead of turning water into wine, as he did in Galilee, He would be rather disposed to turn all strong drink into water… The people of Ellacombe had better renounce the name of religionists, and call themselves ‘alcoholists’.”

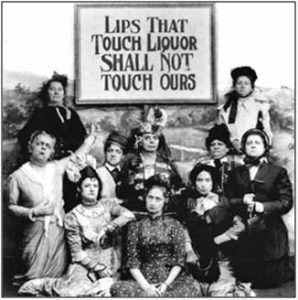

This perceived scourge of the working class was opposed by temperance campaigners. In March 1832 Joseph Livesey started his Temperance Movement in Preston, Lancashire, requiring followers to sign a pledge of total abstinence. The British Association for the Promotion of Temperance was established by 1835, and in 1847 the Band of Hope was founded in Leeds, to save working class children from the perils of drink. In Torquay a Temperance Society was started in 1843 to take the place of, “a Society in which entire abstinence was not a necessary qualification for membership…” Alongside the new society, the Torquay campaigners were joined by “Bands of Hope, good Templar Lodges, local branches of the Church of England Temperance Societies, and parochial Temperance Guilds”. Incidentally, the term teetotal probably comes from the T in total, with some activists signing a ‘T’ after their name to signify a pledge for total abstinence.

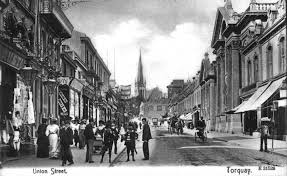

As working men were seen as most open to temptation, a series of British Workman Public Houses were opened, “where refreshments of all kinds can be had, but no intoxicating liquors”. The first was in Union St in November 1872, followed by Vaughan Parade – for the benefit of fishermen and sailors – and then Market St. Pictured is the Sailors Rest at 32 Victoria Parade (now the shop ‘Seabreeze’), which provided accommodation and a Temperance restaurant for sailors (pictured below).

However, they don’t seem to have been entirely successful. From the Torquay Directory in 1877, “On Friday night, the apparently inanimate body of a gentleman was found stretched out on the footpath of the Strand. The body was placed in a cab and taken to the Infirmary where a careful examination showed that insensibility was due, not to apoplexy, but drunkenness.”

Nevertheless, the campaign against drink continued. For example, we’ve had a number of London Inns in Torquay over the years – one of these was in Pimlico until February 1909 when it was converted to a Christian Mission Room and Club House for, “the social improvement and elevation of poor people”. At the opening ceremony, Torquay’s Mayor, Colonel Scragge, said: “No one could be acquainted with such clubs without recognising that they supplied a sore need and accomplished a good work in keeping men from public houses and in elevating their character”. He applauded “the effort that was being made to improve the conditions in which a large number of people lived in the little known but thickly populated district behind Union Street”.

The Mayor had been involved in saving us from ourselves before. When “driving through Babbacombe on a wet and cold November day he found a group of working men standing at a street corner. ‘Have you no place you can go?’ he asked. One, in reply, pointed to the swinging doors of a public house opposite.” Then the Mayor determined to open what became Babbacombe’s St Anne’s Institute (pictured below).

It was not until drinking became an issue of national security that the government decided to act. During the First World War, the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, stated that Britain was “fighting Germans, Austrians and Drink, and as far as I can see the greatest of these foes is Drink”. A total ban – like the Americans Prohibition – was considered but it was quickly realised that rioting would be the consequence. Instead laws were introduced reducing the strength of beer, banning the buying of rounds in pubs and restricting pub opening hours. By the end of the war, British alcohol consumption had fallen by almost two-thirds.

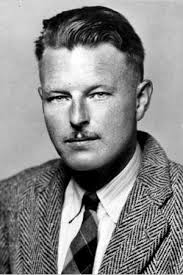

For some of us social drinking can turn into alcohol abuse that damages health and takes lives. One victim was the author Malcolm Lowry who visited Torquay in the early 1930s. Malcolm (pictured below) found Torquay to be, “a funny, tawdry place, on the sea, like a pub picture of China gone crazy, only it’s got speedboats & plenty of sea & diving boards & this afternoon a cruiser, god knows where that came from.” Malcolm’s alcoholism caused severe paranoia and delusions. While swimming on Torre Abbey Sands he believed he was being followed, “You know they put a nurse on me, to shadow me. You know he was out there in the middle… there… in the afternoon. I turned over on my back to float and there he was swimming towards me. Oh, he’s gone. He’s like that. He just appears and disappears”. Malcom died at the age of 47.

We’re still drinking, but in different ways – the supermarket has taken over from the pub. Consequently, the numbers of establishments have been in decline for many years. Nationally there were 99,000 pubs in 1905 but just 48,000 today – 29 pubs a week are being lost. In the past decade or so we’ve lost, The Alpine, Post Horn, Upton Vale, The Sportsman’s, The Pelican, The Railway and many more. Some of the first pubs to go were the victims of town centre redevelopment. For instance, when The Prince of Wales closed in September 1961 the licensee Mrs Harriet Steer said: “People’s drinking habits change with the times. Years ago, when a pint of beer was four pence and a pint of bitter sixpence, men used to come in their work clothes. Now they go home first, wash and change and arrive clean and fresh. Saturday nights, when the shops used to stay open until late, Union Street used to look like a fair. People from the country used to come up to shop. There were fruit barrows up the roads and meat was auctioned.” The Prince of Wales was demolished and the site is now occupied by ‘Primani’.

Home entertainment, health concerns, the smoking ban and competition from supermarkets have all eroded the traditional pub and the Torquay drinking experience – the photo above was taken in the Clipper Inn before it closed in 2017. Nonetheless, we remain a party town and Friday and Saturday night carousing continues. This weekend, from Hele to the Harbourside, Torquay’s drinkers will be carrying on a long tradition. Just remember to be careful out there.